Wright brothers

A bicycle shop in Ohio provided the mechanical intuition and capital that academia lacked.

A bicycle shop in Ohio provided the mechanical intuition and capital that academia lacked.

Wilbur and Orville Wright were not theoretical scientists or government-funded engineers; they were self-taught mechanics who ran a successful bicycle business in Dayton. This background was their secret weapon. Bicycles taught them that a moving vehicle is inherently unstable and requires constant, active control from the operator—a radical departure from the "stable ship" mentality of their contemporaries.

By funding their experiments entirely through bicycle sales, they remained independent. They avoided the pressure of investors and the public ridicule that followed high-profile, state-funded failures like those of Samuel Langley. Their shop also gave them the tools to build their own engines and airframes with surgical precision.

While rivals focused on raw engine power, the Wrights prioritized the "three-axis" control required to master the air.

While rivals focused on raw engine power, the Wrights prioritized the "three-axis" control required to master the air.

The prevailing wisdom of the 19th century was that flight was a problem of propulsion: find a big enough engine, and the machine would stay up. The Wrights realized that staying up was useless if the pilot couldn't steer. They focused on "three-axis control"—roll, pitch, and yaw—which allowed a pilot to maintain equilibrium and navigate turns effectively.

Their most ingenious invention was "wing-warping," a system of pulleys that twisted the wing tips to change the plane's lift on either side. This provided the "roll" control that is still the fundamental principle of modern aviation. They solved the pilot's problem before they even attempted to solve the engine's problem.

Precision wind-tunnel testing allowed them to correct established aerodynamic errors that had grounded earlier pioneers.

Precision wind-tunnel testing allowed them to correct established aerodynamic errors that had grounded earlier pioneers.

In 1901, after several failed glider tests, the brothers realized that the "Smeaton coefficient"—a mathematical value used for 100 years to calculate lift—was wrong. Rather than giving up, they built a homemade wind tunnel in their shop and tested over 200 different wing shapes.

This rigorous empirical data allowed them to design the first truly efficient propellers and wings. They discovered that a propeller is essentially just a rotating wing, a realization that allowed them to achieve 66% efficiency with their first design, a feat that far surpassed any other engineer of the era.

The 1903 Kitty Hawk flight was less a "discovery" and more the proof of a reproducible engineering system.

The 1903 Kitty Hawk flight was less a "discovery" and more the proof of a reproducible engineering system.

On December 17, 1903, at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, the Wrights achieved the first powered, controlled, sustained flight of a heavier-than-air aircraft. While the first flight lasted only 12 seconds and covered 120 feet, it wasn't a fluke. They flew four times that day, with Wilbur eventually staying aloft for 59 seconds.

What made the Wright Flyer significant wasn't just that it flew, but that it was a system. It integrated a lightweight engine, a custom-built airframe, and a sophisticated control interface. They didn't just stumble into the sky; they engineered a way to stay there.

A decade of aggressive patent litigation transformed the brothers from visionary inventors into industry obstacles.

A decade of aggressive patent litigation transformed the brothers from visionary inventors into industry obstacles.

Success brought a shift in the brothers' focus from innovation to protectionism. They held a broad patent on their flight control system and spent years suing rivals like Glenn Curtiss. This "Patent War" grew so bitter that it effectively stifled the development of the American aviation industry, allowing European designers to overtake them.

The conflict was so disruptive that the U.S. government eventually forced a "patent pool" during World War I, requiring companies to share technology to ensure the military had functional planes. This legal era tarnished their public image, moving them from the role of pioneering heroes to litigious gatekeepers.

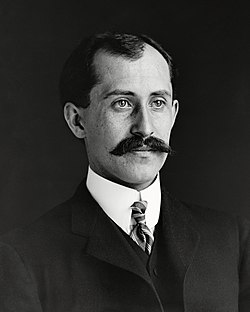

Orville Wright in 1905

Orville (left) and Wilbur Wright as children in 1876

Wright brothers' home at 7 Hawthorn Street, Dayton, c. 1900. Wilbur and Orville built the covered wrap-around porch in the 1890s.

The Wright brothers' bicycle at the National Air and Space Museum

Wright 1899 kite: front and side views, with control sticks. Wing-warping is shown in lower view. (Wright brothers' drawing in Library of Congress.)

Park Ranger Tom White demonstrates a replica of the Wright brothers' 1899 box kite at the Wright Brothers National Memorial.

Chanute's hang glider of 1896. The pilot may be Augustus Herring.

The 1900 glider. No photo was taken with a pilot aboard.

Orville with the 1901 glider, its nose pointed skyward; it had no tail.

Replica of the Wright Brothers' wind tunnel at the Virginia Air and Space Center

At left, 1901 glider flown by Wilbur (left) and Orville. At right, 1902 glider flown by Wilbur (right) and Dan Tate, their helper. Dramatic improvement in performance is apparent. The 1901 glider flies at a steep angle of attack due to poor lift and high drag. In contrast, the 1902 glider flies at a much flatter angle and holds up its tether lines almost vertically, clearly demonstrating a much better lift-to-drag ratio.

Wilbur Wright pilots the 1902 glider over the Kill Devil Hills, October 10, 1902. The single rear rudder is steerable; it replaced the original fixed double rudder.

Wilbur makes a turn using wing-warping and the movable rudder, October 24, 1902.

A Wright engine, serial number 17, c. 1910, on display at the New England Air Museum

The first flight of the Wright Flyer, December 17, 1903, Orville piloting, Wilbur running at wingtip