Wine

Wine transitioned from a Neolithic discovery in Georgia to a global religious and commercial pillar.

Wine transitioned from a Neolithic discovery in Georgia to a global religious and commercial pillar.

The earliest evidence of winemaking dates back to 6000 BCE in present-day Georgia. From there, it became a primary cultural export for the Phoenicians and Greeks, eventually reaching an industrial scale under the Roman Empire. During the Middle Ages, Christian monasteries became the stewards of viticulture, refining techniques for the Eucharist and establishing many of the world’s most prestigious vineyard sites.

The 16th century saw the "Old World" tradition follow colonial expansion into Mexico, Peru, and later California and Australia. This global spread transformed wine from a local agricultural product into a high-stakes trade commodity. Today, wine is no longer just a drink; it is a global investment asset, an academic discipline, and a centerpiece of culinary arts.

The 19th-century "Great Blight" forced a permanent biological union between European vines and American roots.

The 19th-century "Great Blight" forced a permanent biological union between European vines and American roots.

In the late 1800s, the invasive aphid phylloxera—brought from America—nearly destroyed every vineyard in Europe by eating the roots of the native Vitis vinifera vines. The industry was saved by a counterintuitive solution: grafting European vines onto American rootstocks, which were naturally resistant to the pest. This biological hybridity remains the standard for almost all modern wine production.

This crisis catalyzed the creation of strict regulatory systems, such as France’s Appellation d'origine contrôlée (AOC) in 1947. These laws were designed to restore consumer confidence by mandating specific grape varieties, yields, and production methods. This shift from quantity to quality-controlled marketing defined the modern era of "discerning" wine consumption.

Terroir and microbial chemistry transform simple grape sugar into a complex, shelf-stable liquid.

Terroir and microbial chemistry transform simple grape sugar into a complex, shelf-stable liquid.

While fruit wines exist, "wine" almost exclusively refers to fermented grape juice because grapes possess the unique balance of sugar, acid, and nutrients required for stable fermentation. The process relies on yeast—either wild or cultured—to convert sugars into alcohol, heat, and CO2. Many wines undergo a secondary "malolactic" fermentation, where bacteria convert harsh malic acid into softer, creamy lactic acid.

The character of the final liquid is dictated by "terroir"—the specific intersection of soil chemistry, vineyard slope, and climate. Traditionally restricted to a narrow band between 30 and 50 degrees latitude, viticulture is currently shifting due to climate change and technological advances, pushing the "wine frontier" further north and south into once-inhospitable regions.

Global classifications balance rigid European tradition against the experimental flexibility of the New World.

Global classifications balance rigid European tradition against the experimental flexibility of the New World.

European wine identity is tied to geography. Systems like Italy’s DOCG or Germany’s Qualitätswein classify wine by where it was grown (e.g., Bordeaux or Chianti), assuming that the region’s rules dictate the quality. These systems are often rigid, strictly limiting which grapes can be planted and how they must be harvested to carry the regional name.

Conversely, "New World" producers in the Americas, Australia, and New Zealand prioritize the varietal (the specific grape type) and producer brand. These regions generally avoid restrictive laws on yields or techniques, favoring innovation and experimentation. While European labels tell you the land's history, New World labels focus on the grape’s chemistry and the winemaker's intent.

Serving and storage are tactical manipulations of volatility, sweetness, and oxygen.

Serving and storage are tactical manipulations of volatility, sweetness, and oxygen.

Serving wine is an exercise in applied chemistry. Temperature acts as a flavor throttle: warmth increases the "aromatic intensity" by allowing volatile compounds to evaporate, but it also makes alcohol more pungent. Conversely, cooling suppresses aroma but highlights acidity and balances high sugar levels. This is why sparkling and sweet wines are served coldest, while complex reds are served at "cool room temperature."

Oxygen is both a tool and a threat. Decanting "opens up" young wines by aerating them to release flavors, but can rapidly oxidize and ruin older, more fragile vintages. Even the choice of closure is a debate between tradition and science; while natural cork is prized for its ritual and aging potential, it is prone to "cork taint," leading many producers to adopt screwcaps and synthetic stoppers for consistency.

Image from Wikipedia

The Areni-1 cave in Armenia is home to the world's oldest known winery.

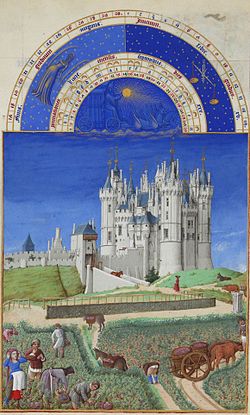

Grape harvesting at Château de Saumur, depicted in Les Très Riches Heures du duc de Berry (c. 1416)

Wine production

Vineyard in Moldova.

Kvevris, traditional Georgian wine-making vessels made of clay.

Natural (top) and synthetic (bottom) wine corks

Italian wine bottleneck markings showing DOCG and DOC status

Vintage Champagne

Tilting the glass and judging a wine's color against a white background is often one of the first steps in tasting a wine.

Wine consumption per person, 2019

Wine as a share of total alcohol consumption, 2016

Allegory of Gluttony and Lust by Hieronymus Bosch, c. 1495 – c. 1500

Jesus making wine from water at the Marriage at Cana