Wheat

Wheat is a biological machine designed to prioritize grain production through specialized "flag leaves" and deep root systems.

Wheat is a biological machine designed to prioritize grain production through specialized "flag leaves" and deep root systems.

Unlike many grasses, wheat focuses its energy through a "telescoping" growth pattern that culminates in the flag leaf—the final leaf produced before flowering. This specific leaf is denser and more photosynthetically active than the others, acting as the primary power station that pumps carbohydrates into the developing ear. Its health is so vital that it dictates the final crop yield.

Underground, wheat roots are among the deepest of all arable crops, reaching up to two meters to find water. The plant manages a sophisticated energy trade-off: it stores "fructans" (energy reserves) in its stem to survive drought or disease. Depending on the climate, different varieties are bred to prioritize either deep root growth for water-scarce regions or stem-stored energy for areas where disease pressure is high.

Human civilization was built on a genetic mutation that stripped wheat of its natural ability to survive in the wild.

Human civilization was built on a genetic mutation that stripped wheat of its natural ability to survive in the wild.

Wild wheat is designed to "shatter"—its seed heads break apart easily so the wind can disperse them. Domestication occurred because early humans selected for "sports," or mutant plants with a toughened rachis (the stem holding the seeds). These mutants couldn't spread their own seeds, making them evolutionary dead-ends in the wild, but perfect for farmers who wanted the grains to stay attached for easier harvesting.

This transition from wild harvesting to intentional farming happened around 9600 BC in the Fertile Crescent. Interestingly, this domestication likely wasn't a "eureka" moment but an incidental result of repeated harvesting. By saving the seeds that stayed on the stalk, humans unintentionally re-engineered the plant's biology, eventually making wheat entirely dependent on human intervention for its reproduction.

Modern bread wheat is a "genomic stack" created by the accidental hybridization of three different wild species.

Modern bread wheat is a "genomic stack" created by the accidental hybridization of three different wild species.

While humans are diploids (two sets of chromosomes), most wheat used for bread is hexaploid—it contains six sets of chromosomes. This complex genetic structure didn't happen in a lab; it occurred in farmers' fields thousands of years ago when domesticated emmer wheat (a tetraploid) naturally cross-bred with wild goatgrass.

This "polyploidy" is what gives wheat its remarkable adaptability. Because it has multiple sets of genes, it can thrive in a vast range of environments, from the edges of the Arctic to the equator. This genetic redundancy also contributes to the unique properties of its proteins, particularly the gluten that allows dough to rise into the porous, airy texture of modern bread.

Wheat occupies a larger footprint on Earth than any other food crop, making it the primary driver of global agricultural trade.

Wheat occupies a larger footprint on Earth than any other food crop, making it the primary driver of global agricultural trade.

In 2021, wheat was cultivated on over 220 million hectares—a land mass larger than the size of Greenland. While maize (corn) technically produces a higher total tonnage, wheat is the undisputed king of international commerce; the world trade in wheat exceeds that of all other crops combined. Since 1960, global production has tripled, fueled by the "Green Revolution" and increasing industrial demand.

This dominance is largely due to its storage life and the industrial utility of gluten. Beyond being a primary source of carbohydrates and vegetable protein (roughly 13% of its content), wheat's versatility allows it to be transformed into everything from thickeners for the food industry to straw for construction and fuel. However, its ubiquity has also highlighted health sensitivities, as a small but significant portion of the population reacts to the very gluten proteins that make the crop so industrially valuable.

Image from Wikipedia

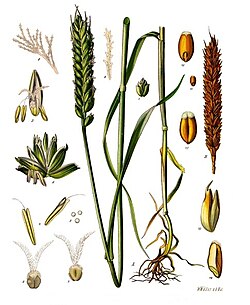

A: Plant; B ripe ear of corn; 1 spikelet before flowering; 2 the same, flowering and spread, enlarged; 3 flowers with glumes; 4 stamens; 5 pollen; 6 and 7 ovaries with juice scales; 8 and 9 parts of the scar; 10 fruit husks; 11, 12, 13 seeds, natural size and enlarged; 14 the same cut up, enlarged.

Origin and 21st century production areas of wheat

Sickles with stone microblades were used to harvest wheat in the Neolithic period, c. 8500–4000 BC

Sumerian cylinder seal impression dating to c. 3200 BC showing an ensi and his acolyte feeding a sacred herd wheat stalks; Ninurta was an agricultural deity and, in a poem known as the "Sumerian Georgica", he offers detailed advice on farming

Threshing of wheat in ancient Egypt

Traditional wheat harvesting India, 2012

Wheat origins by repeated hybridization and polyploidy. Not all species are shown.

Hulled wheat and einkorn. Note how the einkorn ear breaks down into intact spikelets.

Wheat is used in a wide variety of foods.

Wheat production

Wheat-growing areas of the world

World production of primary crops by main commodities

Wheat prices in England, 1264–1996

Wheat developmental stages on the BBCH and Zadok's scales