Treaty of Versailles

The treaty was signed under the duress of a lethal naval blockade that continued long after the fighting stopped.

The treaty was signed under the duress of a lethal naval blockade that continued long after the fighting stopped.

While the Armistice of 11 November 1918 ended active combat, the state of war persisted for months during negotiations. To ensure German cooperation, the Allied Powers maintained a naval blockade that prevented food and raw materials from entering the country. Estimates of civilian deaths resulting from this "starvation blockade" range from 100,000 to over 700,000, creating a desperate atmosphere that some Germans viewed as a "peace of violence" rather than a negotiated settlement.

Germany was entirely excluded from the negotiations at the Paris Peace Conference. When they were finally presented with the terms in June 1919, they were given no room to bargain. This exclusion, combined with the threat of renewed invasion and the ongoing blockade, forced the German delegation to sign a document they had no hand in drafting.

The "Big Four" leaders were trapped between Wilson’s global idealism and the raw security needs of a devastated Europe.

The "Big Four" leaders were trapped between Wilson’s global idealism and the raw security needs of a devastated Europe.

The negotiations were dominated by the "Big Four": Woodrow Wilson (USA), David Lloyd George (UK), Georges Clemenceau (France), and Vittorio Emanuele Orlando (Italy). Wilson arrived with his "Fourteen Points," a blueprint for a new world order based on self-determination, transparency, and a League of Nations. He aimed to move past the "old diplomacy" of secret alliances and territorial grabs.

However, Clemenceau and Lloyd George faced different pressures. France had lost 1.3 million soldiers and saw its industrial heartland systematically destroyed by German forces. For Clemenceau, the treaty wasn't about abstract justice; it was about physical security. He famously reminded Wilson that while America was protected by an ocean, France was not. This clash between Wilsonian idealism and European realism resulted in a series of awkward compromises.

Article 231 transformed moral "War Guilt" into a legal mechanism for indefinite financial reparations.

Article 231 transformed moral "War Guilt" into a legal mechanism for indefinite financial reparations.

The most controversial element of the treaty was the "War Guilt Clause." Article 231 forced Germany to accept full responsibility for all loss and damage caused by the war. While often viewed as a psychological blow to German national pride, its primary function was legal: by establishing Germany as the sole aggressor, the Allies created the legal foundation to demand massive, unspecified reparations.

The financial burden was intended to accomplish two things: help rebuild the devastated regions of France and Belgium, and keep the German economy weak enough to prevent a military resurgence. Critics like John Maynard Keynes argued these reparations were "Carthaginian"—so harsh they would inevitably lead to economic collapse and future conflict. Conversely, some Allied leaders felt the terms were still too lenient to truly neutralize Germany.

The treaty failed as a "Middle Way" by being too harsh to reconcile Germany but too weak to permanently restrain it.

The treaty failed as a "Middle Way" by being too harsh to reconcile Germany but too weak to permanently restrain it.

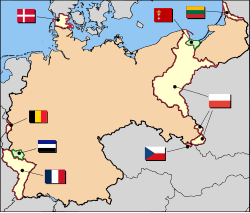

The final document satisfied almost no one. France did not get the permanent Rhine frontier it wanted for security; the United States Senate refused to ratify the treaty or join the League of Nations; and Germany was left humiliated but not fundamentally broken. The country lost 13% of its European territory and all of its overseas colonies, yet it remained a unified state with a massive industrial potential.

This "failed compromise" fueled a narrative of betrayal in Germany. The "bitter resentment" mentioned in the text became the primary engine for the rise of the Nazi Party, which used the "shame of Versailles" as a powerful recruiting tool. Instead of creating a lasting peace, the treaty created a volatile status quo that required constant management through later agreements like the Dawes Plan and the Locarno Treaties, eventually collapsing into the Second World War.

Image from Wikipedia

Map showing the Western Front as it stood on 11 November 1918. The German frontier of 1914 had been crossed in the vicinities of Mulhouse, Château-Salins, and Marieulles in Alsace-Lorraine. The post-war bridgeheads over the Rhine are also shown.

The heads of the "Big Four" nations at the Paris Peace Conference, 27 May 1919. From left to right: David Lloyd George, Vittorio Orlando, Georges Clemenceau, and Woodrow Wilson

British Prime Minister David Lloyd George

Germany after Versailles: Administered by the League of Nations Annexed or transferred to neighbouring countries by the treaty, or later via plebiscite and League of Nations action Weimar Germany

German colonies (light blue) were made into League of Nations mandates.

![Workmen decommissioning a heavy gun (likely 28 cm Haubitze L/14 i.R.[citation needed]), to comply with the treaty.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/36/Bundesarchiv_Bild_146-1972-081-03%2C_Zerlegen_eines_schweren_Gesch%C3%BCtzes.jpg/250px-Bundesarchiv_Bild_146-1972-081-03%2C_Zerlegen_eines_schweren_Gesch%C3%BCtzes.jpg)

Workmen decommissioning a heavy gun (likely 28 cm Haubitze L/14 i.R.[citation needed]), to comply with the treaty.

Location of the Rhineland (yellow)

A British news placard announcing the signing of the peace treaty

Senators Borah, Lodge and Johnson refuse Lady Peace a seat, referring to efforts by Republican isolationists to block ratification of the Treaty of Versailles establishing the League of Nations.

German delegates in Versailles: Professor Walther Schücking, Reichspostminister Johannes Giesberts, Justice Minister Otto Landsberg, Foreign Minister Ulrich Graf von Brockdorff-Rantzau, Prussian State President Robert Leinert, and financial advisor Carl Melchior

Demonstration against the treaty in front of the Reichstag

Medal issued by the Japanese authorities in 1919, commemorating the Treaty of Versailles. Obv: Flags of the five allies of World War I. Rev: Peace standing in Oriental attire with the Palace of Versailles in the background

A crowd awaits the plebiscite results in Oppeln

French soldiers in the Ruhr, which resulted in the American withdrawal from the Rhineland