Trail of Tears

A state-sponsored ethnic cleansing displaced 60,000 people to open 25 million acres for white settlement.

A state-sponsored ethnic cleansing displaced 60,000 people to open 25 million acres for white settlement.

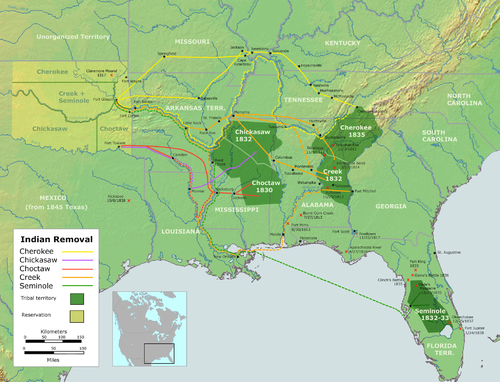

Between 1830 and 1850, the United States government forcibly removed the "Five Civilized Tribes"—the Cherokee, Muscogee, Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw—from their ancestral lands in the Southeast. This wasn't just a relocation; it was a systematic seizure of wealth. By moving these nations to "Indian Territory" (modern-day Oklahoma), the government vacated vast tracts of land that were immediately repurposed for white settlers and the expansion of the cotton-based plantation economy.

The human cost was staggering. Relocated peoples were forced to march through exposure, disease, and starvation. Thousands died either en route or shortly after arrival. While often framed as a tragedy of "nature," many modern scholars categorize the event as a genocide, noting that the displacement also included over 4,000 enslaved Black people who were owned by members of these nations and forced to make the trek alongside them.

The "Vanishing Indian" myth provided the moral cover for systemic land theft and cultural erasure.

The "Vanishing Indian" myth provided the moral cover for systemic land theft and cultural erasure.

The removal policy was fueled by a convenient cultural narrative: the idea that Native Americans were a "vanishing race" whose disappearance was an inevitable byproduct of progress. Figures like novelist James Fenimore Cooper helped cement this idea in the American psyche, framing the loss of Indigenous land as a natural process rather than a result of deliberate political choices. This ideology allowed the U.S. government to evade moral responsibility for the destruction it authored.

Paradoxically, many of the targeted nations had already integrated into the American economic system. The Cherokee and Choctaw, in particular, had adopted Western-style agriculture, written constitutions, and even the practice of chattel slavery. This "civilization" did not protect them; instead, their success made their land more attractive to white squatters and state governments eager to dissolve tribal boundaries.

President Andrew Jackson transformed Indian removal from a passive policy into a violent national priority.

President Andrew Jackson transformed Indian removal from a passive policy into a violent national priority.

While the idea of removal predated his presidency, Andrew Jackson made it his top legislative priority. He viewed Native American nations as "obstacles" to Manifest Destiny and national success. Despite his public claims that emigration should be "voluntary," his administration used coercion, military threats, and the Indian Removal Act of 1830 to extinguish Indian land claims.

Historians remain divided on Jackson's personal intent. Some, like Robert Remini, argue Jackson believed removal was the only way to save the tribes from total extinction at the hands of hostile white settlers. Others, such as Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, point to his history as an "Indian fighter" and his belief in "bleeding enemies" to argue that his goals were overtly violent and expansionist, seeking the total removal of Indigenous presence from the Eastern U.S.

The Supreme Court affirmed Cherokee sovereignty, but the Executive branch chose to ignore the law.

The Supreme Court affirmed Cherokee sovereignty, but the Executive branch chose to ignore the law.

The Trail of Tears represents one of the greatest constitutional crises in American history. In the landmark case Worcester v. Georgia (1832), the Supreme Court ruled that the Cherokee Nation was a distinct community subject only to federal law, meaning the state of Georgia had no authority to seize their lands. Chief Justice John Marshall explicitly stated that the "laws of Georgia can have no force" within Cherokee territory.

However, the Court had no power to enforce its own ruling. President Jackson famously refused to intervene against Georgia, fearing a confrontation with the state's militia would trigger a civil war. By failing to uphold the Court's decision, the Executive branch effectively signaled that treaty rights and legal protections for Native Americans were void if they conflicted with white expansionist interests.

Internal tribal divisions and fraudulent treaties provided the thin legal veneer for forced marches.

Internal tribal divisions and fraudulent treaties provided the thin legal veneer for forced marches.

The actual "trail" began not with a unanimous agreement, but with a fractured leadership. In the case of the Cherokee, a minority faction known as the "Treaty Party" signed the Treaty of New Echota in 1835 without the authorization of the National Council or Principal Chief John Ross. Despite a petition signed by 16,000 Cherokee citizens protesting the fraud, the U.S. Senate ratified the treaty.

This document became the legal pretext for the final, most famous removal in 1838. The majority of the Cherokee remained in their homes until they were rounded up by state militias and federal troops. Broken into groups of roughly 1,000, they began a westward journey through record-breaking cold and snow. The resulting mortality rate was so high that the path became known in the Cherokee language as nu na hi du na tlo hi lu i—the place where they cried.

Image from Wikipedia

A map of the process of Indian Removal, 1830–1838. Oklahoma is depicted in light yellow-green.

George W. Harkins, Choctaw chief

Alexis de Tocqueville, French political thinker and historian

Seminole warrior Tuko-see-mathla, 1834

Selocta Chinnabby (Shelocta) was a Muscogee chief who appealed to Andrew Jackson to reduce the demands for Creek lands at the signing of the Treaty of Fort Jackson.

Historic Marker in Marion, Arkansas, for the Trail of Tears

Cherokee Principal Chief John Ross, photographed before his death in 1866

Elizabeth "Betsy" Brown Stephens (1903), a Cherokee Indian who walked the Trail of Tears in 1838

A Trail of Tears map of Southern Illinois from the USDA – U.S. Forest Service

Walkway map at the Cherokee Removal Memorial Park in Tennessee depicting the routes of the Cherokee on the Trail of Tears, June 2020

Map of National Historic trails