Sinking of the Titanic

A "near-miss" culture and high-speed arrogance turned a common navigational hazard into a catastrophic hull breach.

A "near-miss" culture and high-speed arrogance turned a common navigational hazard into a catastrophic hull breach.

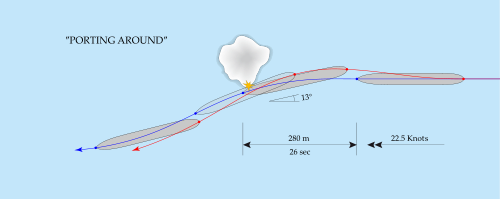

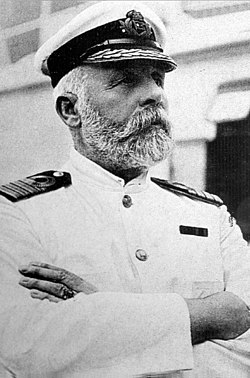

The Titanic was not a victim of a freak accident so much as a victim of its own industry's complacency. Captain Edward Smith was pushing the ship at 22.5 knots—near its top speed—through a known ice field at night. This wasn't unusual for the era; the prevailing wisdom was that ice was a visible obstacle that could be dodged if spotted. However, the sea was abnormally calm that night, meaning there was no surf breaking against the base of icebergs to make them visible from a distance.

When the iceberg was spotted, the ship’s size worked against it. The Titanic was designed to survive a head-on collision or a breach of two compartments, but the "glancing blow" maneuver buckled the hull plates along a 300-foot stretch. By compromising five of its sixteen watertight compartments, the ship’s fate was sealed within minutes. The "unsinkable" design assumed damage would be localized; it had no answer for a longitudinal gash.

Outdated maritime laws prioritized deck aesthetics over safety, ensuring that even a perfect evacuation would leave 1,000 people behind.

Outdated maritime laws prioritized deck aesthetics over safety, ensuring that even a perfect evacuation would leave 1,000 people behind.

The most haunting failure of the Titanic was not the ice, but the math. The British Board of Trade’s regulations were based on a ship's tonnage rather than its passenger capacity. Because of this, the Titanic was legally required to carry boats for only 1,060 people. The White Star Line actually exceeded the law by providing 20 boats for 1,178 people—yet there were over 2,200 souls on board.

The evacuation was further crippled by a lack of training. No lifeboat drill had been held, and many crew members didn't know how many people the davits could support. Fearful that the boats would buckle if fully loaded, they lowered many half-empty. The first boat to leave, with a capacity of 40, carried only 12 people. By the time the crew realized the boats could hold the weight, the ship was listing too heavily to launch the remaining craft.

Social stratification and "labyrinthine" architecture made survival a function of class.

Social stratification and "labyrinthine" architecture made survival a function of class.

Survival on the Titanic was largely a matter of where you slept. First-class passengers had direct access to the boat deck and were the first to be notified of the danger. In contrast, third-class passengers were housed in the lowest decks, separated from the upper decks by a maze of corridors and gates designed to comply with U.S. immigration laws.

There was no general alarm system. While first-class stewards knocked on every door, steerage passengers were often left to find their own way through the rising water. The results were stark: roughly 60% of first-class passengers survived, compared to only 25% of those in third class. While there is little evidence of a formal policy to "lock in" the poor, the ship's physical and social architecture acted as a passive death sentence.

The tragedy exposed a fatal gap in wireless communication protocols that allowed a nearby ship to ignore the disaster.

The tragedy exposed a fatal gap in wireless communication protocols that allowed a nearby ship to ignore the disaster.

In 1912, wireless telegraphy was seen as a luxury convenience for passengers rather than a critical safety tool. This led to a communication breakdown with the SS Californian, which was less than 20 miles away when the Titanic struck the ice. The Californian had stopped for the night due to ice and its lone radio operator had gone to bed just minutes before the Titanic's first distress call.

The Californian’s crew actually saw the Titanic’s distress rockets but misinterpreted them as company signals or fireworks. Because there was no legal requirement for a 24-hour radio watch, the closest potential savior remained stationary while the "unsinkable" ship went under. It was only the RMS Carpathia, 58 miles away, that caught the signal by chance and raced through the ice to rescue the survivors in the boats.

The disaster ended the era of maritime "best guesses" and birthed modern international safety standards.

The disaster ended the era of maritime "best guesses" and birthed modern international safety standards.

The sinking of the Titanic was a "black swan" event that fundamentally changed how the world approaches risk. Before 1912, safety was largely at the discretion of individual shipping lines. After the inquiries in the U.S. and Britain, the first International Convention for the Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) was formed in 1914. This treaty remains the most important international maritime safety document today.

Because of the Titanic, it is now mandatory for every ship to have lifeboat capacity for every person on board, for radio stations to be manned 24 hours a day, and for red rockets to be recognized strictly as distress signals. The tragedy also led to the creation of the International Ice Patrol, which still monitors the North Atlantic today. We still live under the safety shadow of 1912; every modern cruise ship drill is a direct response to the specific failures of that night.

Painting of a ship sinking by the bow, with people rowing a lifeboat in the foreground and other people in the water. Icebergs are visible in the background.

Titanic on sea trials on 2 April 1912

SS New York in her near collision with the Titanic on 10 April 1912

The Titanic's itinerary across the North Atlantic from Fastnet Lighthouse in southern Ireland to Ambrose Light in the Lower New York Bay

The iceberg thought to have been hit by the Titanic, photographed on the morning of 15 April 1912 by SS Prinz Adalbert's chief steward. The iceberg was reported to have a streak of red paint from a ship's hull along its waterline on one side.

Titanic's course during her attempted "port around" Course travelled by the bow Course travelled by the stern

Drawing of the iceberg collision

Side view of the iceberg buckling the plates, popping rivets, and damaging a sequence of compartments of the Titanic

Bulkhead arrangement with damaged areas shown in green

Titanic Captain Edward Smith in 1911

Map of the location of the catastrophe and other ships in the vicinity, early morning of 15 April 1912

Lifeboat No. 6 under capacity

The Sad Parting, a 1912 illustration

Distress signal sent at about 01:40 by Titanic's radio operator, Jack Phillips, to the Russian American Line ship SS Birma. This was one of Titanic's last intelligible radio messages.

Lifeboat No. 15 being nearly lowered onto lifeboat No. 13, depicted in an illustration by Charles Dixon