1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre

The movement was ignited by the mourning of a purged reformer, exposing deep-seated anxieties about corruption and economic instability.

The movement was ignited by the mourning of a purged reformer, exposing deep-seated anxieties about corruption and economic instability.

The protests didn't start as a revolution, but as a funeral. When Hu Yaobang, a deposed reformist leader who had championed political openness, died in April 1989, students gathered in Tiananmen Square to mourn him. This mourning quickly pivoted into a protest against "crony capitalism" and a demand for greater transparency, freedom of the press, and government accountability.

At its peak, nearly a million people occupied the square. While often framed purely as a "pro-democracy" movement in the West, the participants were a diverse and sometimes fractured coalition. Some activists wanted Western-style liberal democracy, while workers were more concerned with 30% inflation and the perceived corruption of "princelings"—the children of elite party officials who were profiting from China's transition to a market economy.

A paralyzing rift within the Chinese Communist Party leadership turned a student protest into an existential threat to the regime.

A paralyzing rift within the Chinese Communist Party leadership turned a student protest into an existential threat to the regime.

The movement lasted seven weeks largely because the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) was paralyzed by a high-stakes internal split. General Secretary Zhao Ziyang advocated for dialogue and conciliation, believing the students' concerns about corruption were legitimate. Opposing him were hardliners led by Premier Li Peng and elder statesman Deng Xiaoping, who viewed the protests as a "counter-revolutionary riot" designed to overthow the party.

By late May, the hardliners won the power struggle. Zhao Ziyang was purged and placed under house arrest—where he remained until his death 16 years later—and martial law was declared. This internal victory signaled that the state would prioritize "stability" and party survival above all else, a doctrine that has defined Chinese governance ever since.

The decision to clear the square with combat troops transformed a civil standoff into a globally televised massacre.

The decision to clear the square with combat troops transformed a civil standoff into a globally televised massacre.

On the night of June 3 and the early morning of June 4, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) advanced toward central Beijing using assault rifles and tanks. Most of the violence occurred not inside the square itself, but on the roads leading to it, such as Changan Avenue. Civilians and protesters attempted to block the military's path using buses and human chains; the military responded with lethal force.

The death toll remains a state secret and a matter of intense debate. The official Chinese government figure was roughly near 300 (including soldiers), while the Chinese Red Cross initially estimated 2,600 deaths, and foreign journalists reported figures ranging from several hundred to several thousand. The iconic "Tank Man"—an unidentified individual who blocked a column of tanks the following day—became the global symbol of this lopsided defiance.

Systematic censorship and the "Great Firewall" have effectively erased the event from China's domestic consciousness.

Systematic censorship and the "Great Firewall" have effectively erased the event from China's domestic consciousness.

In the decades since, the CCP has achieved a near-total "rectification" of the event within mainland China. It is the ultimate "black hole" in the Chinese internet; every June, keywords related to the date, the "Goddess of Democracy," or even cryptic emojis are scrubbed by automated filters. Younger generations in China often grow up with no knowledge of the massacre, or are taught a narrative where "clearing the square" was a necessary, peaceful action to ensure the economic boom that followed.

Internationally, the massacre ended the "honeymoon period" between the West and China that had characterized the 1980s. It triggered long-standing arms embargos and solidified a global perception of the CCP as a regime willing to use ultimate violence to maintain domestic control. What was briefly a symbol of potential opening became the foundation for the modern Chinese surveillance state.

Image from Wikipedia

A slogan inside the Former Residence of Hu Yaobang, a leading reformist whose death triggered the Tiananmen Square protests in 1989

Deng Xiaoping (1904–1997) was the Paramount Leader of China.

General Secretary Zhao Ziyang (left) who pushed for dialogue with students and Premier Li Peng (right) who declared martial law and backed military action

Han Dongfang, founder of the Beijing Workers' Autonomous Federation

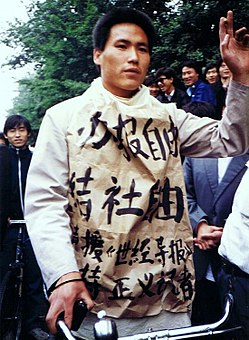

Photo of Pu Zhiqiang, student protester at Tiananmen, taken on 10 May. The words say: "We want the freedom of newspapers, freedom of associations, also to support the World Economic Herald, and support those just journalists."

Wen Jiabao, then chief of the Party's General Office, accompanied Zhao Ziyang to meet students in the square, surviving the political purge of the party's liberals and later serving as Premier from 2003 to 2013.

The Type 59 main battle tank, here on display at the Military Museum of the Chinese People's Revolution in western Beijing, was deployed by the People's Liberation Army on 3 June 1989.

Type 63 armored personnel carrier deployed by the People's Liberation Army in Beijing in 1989

Type 56 assault rifle, used by soldiers during the crackdown

A mural of the "Tank Man" in Cologne, Germany

A burned-out vehicle on a Beijing street a few days after 6 June

Jiang Zemin (1926–2022), the party secretary of Shanghai, where student protests were subdued largely without violence, was promoted to succeed Zhao Ziyang as the party General Secretary in 1989.

Monument in Memory of Chinese from Tiananmen in Wrocław, Poland

Candlelight vigil in Hong Kong in 2009 on the 20th anniversary of the June 4 incident