Thermodynamics

Thermodynamics bridges the gap between measurable heat and the abstract mechanics of work and energy.

Thermodynamics bridges the gap between measurable heat and the abstract mechanics of work and energy.

At its core, thermodynamics is the study of how heat, work, and temperature relate to energy and entropy. It transforms "heat"—once a mysterious fluid-like concept—into a quantitative description of how energy moves through physical systems. By focusing on macroscopic properties like pressure and volume, it allows us to predict the behavior of matter without needing to track every individual atom.

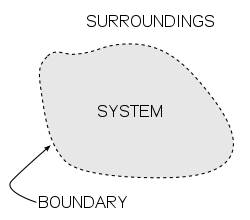

The field is built on the concept of a "system" and its "surroundings." Whether it is a steam piston or a living cell, scientists use equations of state to define how a system’s internal energy changes when it interacts with the outside world. This framework is essential for determining equilibrium—the state where no more "useful" work can be extracted.

The discipline was born from a practical obsession with making steam engines efficient enough to win wars.

The discipline was born from a practical obsession with making steam engines efficient enough to win wars.

Thermodynamics did not begin in a pristine lab; it began with the grunt work of the Industrial Revolution. In the 17th century, Otto von Guericke built the first vacuum pump to disprove Aristotle’s claim that "nature abhors a vacuum." This led to the discovery of Boyle’s Law and the creation of "steam digesters," which eventually evolved into the first crude engines by Thomas Newcomen and James Watt.

The science was formalized by Sadi Carnot, often called the "father of thermodynamics." In 1824, he published a treatise on engine efficiency, believing that superior steam power was the key to France's success in the Napoleonic Wars. His work on the "Carnot cycle" provided the first sound basis for how heat could be converted into motive power, turning a messy engineering problem into a rigorous branch of physics.

Four universal laws dictate how energy moves, defining the nature of temperature and the inevitable increase of disorder.

Four universal laws dictate how energy moves, defining the nature of temperature and the inevitable increase of disorder.

The framework of thermodynamics rests on a set of "axiomatic" laws. The Zeroth Law, though named last, is the most fundamental: it establishes that if two systems are in equilibrium with a third, they are in equilibrium with each other. This provides the first empirical definition of temperature, justifying the use of thermometers.

The First Law is the principle of conservation; it states that energy can be transferred as heat or work, but it cannot be created or destroyed. The Second Law introduces the concept of entropy, defining the "arrow of time." It dictates that systems naturally evolve toward a state of disorder, placing a hard limit on how much work can be extracted from any process and ensuring that no engine can ever be 100% efficient.

While classical thermodynamics observes the world at a human scale, statistical mechanics reveals that heat is just the collective chaos of atoms.

While classical thermodynamics observes the world at a human scale, statistical mechanics reveals that heat is just the collective chaos of atoms.

There are two ways to view the "heat" in a system. Classical thermodynamics is macroscopic; it deals with what we can see and measure directly, like the pressure in a tire. It treats matter as a continuous medium. However, in the late 19th century, physicists like Ludwig Boltzmann and James Clerk Maxwell developed Statistical Mechanics to explain these bulk properties through the behavior of individual atoms.

Statistical thermodynamics proves that what we feel as "temperature" is actually the average kinetic energy of trillions of moving particles. This microscopic view explains classical laws as the result of probability: while a single molecule’s path is random, the behavior of an entire "ensemble" of particles is remarkably predictable through statistics.

Modern thermodynamics governs everything from chemical "spontaneity" to the lifespan of black holes.

Modern thermodynamics governs everything from chemical "spontaneity" to the lifespan of black holes.

The initial focus on mechanical engines quickly expanded into Chemical Thermodynamics. By studying entropy, chemists can determine if a reaction will occur "spontaneously" or if it requires an external energy boost. This is the foundation of modern chemical engineering, materials science, and even cell biology, explaining how our bodies convert food into the energy needed to sustain life.

Beyond chemistry, the field has branched into Equilibrium and Non-Equilibrium thermodynamics. While classical studies focus on stable systems, Non-Equilibrium thermodynamics attempts to map the flux of matter and energy in nature’s more chaotic systems, such as weather patterns and ecosystems. The reach of these laws is so absolute that they are even applied to the study of black holes and the eventual "heat death" of the universe.

The thermodynamicists of the original eight founding schools of thermodynamics. The schools with the most-lasting influence on the modern versions of thermodynamics are the Berlin school, particularly Rudolf Clausius's 1865 textbook The Mechanical Theory of Heat, the Vienna school, with the statistical mechanics of Ludwig Boltzmann, and the Gibbsian school at Yale University of Willard Gibbs' 1876 and his book On the Equilibrium of Heterogeneous Substances which launched chemical thermodynamics.

Annotated color version of the original 1824 Carnot heat engine showing the hot body (boiler), working body (system, steam), and cold body (water), the letters labeled according to the stopping points in Carnot cycle

Opening a bottle of sparkling wine (high-speed photography). The sudden drop of pressure causes a huge drop of temperature. The moisture in the air freezes, creating a smoke of tiny ice crystals.

A diagram of a generic thermodynamic system

Image from Wikipedia