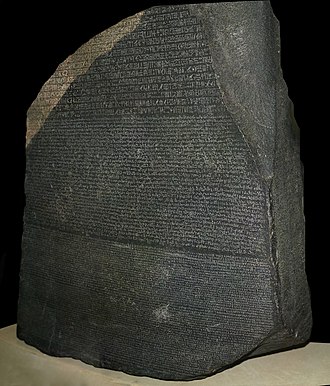

Rosetta Stone

The stone was a piece of mass-produced political propaganda designed to bolster a fragile dynasty.

The stone was a piece of mass-produced political propaganda designed to bolster a fragile dynasty.

The Rosetta Stone is not a unique literary masterpiece; it is a fragment of a "donation decree" issued in 196 BC by a council of priests. It affirms the royal cult of the 13-year-old Ptolemy V, a Greek king ruling an Egyptian populace. To secure the throne during a period of civil unrest, the decree granted tax breaks to the priesthood and promised the king's eternal devotion to the gods.

Because the decree was meant for everyone—the ruling elite, the bureaucrats, and the priests—it was carved into stelae and placed in temples across Egypt. This specific slab survived only because it was later recycled as building material for a medieval wall in the town of Rashid (Rosetta), where it remained hidden for centuries.

A linguistic "bridge" was built by layering a known administrative language over a forgotten sacred one.

A linguistic "bridge" was built by layering a known administrative language over a forgotten sacred one.

The stone’s brilliance lies in its redundancy. It features the same decree written in three distinct scripts: Ancient Greek (the language of the government), Demotic (the common script of the people), and Hieroglyphic (the sacred script of the gods). By the time the stone was discovered, hieroglyphs had been unreadable for over 1,400 years.

This triple-threat of information provided the ultimate "cheat sheet." Scholars could read the Greek perfectly, allowing them to assume what the other two sections said. It turned the stone from a dusty artifact into a key that could unlock the entire history of a dead civilization, provided someone could map the symbols to the sounds.

A failed military campaign by Napoleon inadvertently launched the modern era of Egyptology.

A failed military campaign by Napoleon inadvertently launched the modern era of Egyptology.

The stone was discovered in 1799 not by an archeologist, but by French soldiers during Napoleon’s Egyptian campaign. While strengthening a fort, a lieutenant named Pierre-François Bouchard spotted the slab built into a wall. Napoleon had brought a "Commission of the Sciences and Arts" with him, and they immediately recognized the stone’s potential significance.

The artifact soon became a literal trophy of war. When the British defeated the French in Egypt in 1801, the surrender treaty specifically demanded the handover of Egyptian antiquities. The Rosetta Stone was hauled to London and placed in the British Museum in 1802, where it has remained the museum’s most-visited object ever since.

Cracking the code required realizing that hieroglyphs were phonemes, not just pictures.

Cracking the code required realizing that hieroglyphs were phonemes, not just pictures.

For centuries, scholars wrongly believed hieroglyphs were purely "ideographic"—that a picture of a bird simply meant "bird." The breakthrough came when Thomas Young and Jean-François Champollion began focusing on "cartouches," the oval loops enclosing royal names. They realized these symbols actually represented sounds, much like an alphabet.

Champollion eventually won the race to decipher the script by using his knowledge of Coptic, the final stage of the ancient Egyptian language. In 1822, he announced he could finally read the names of the pharaohs. This realization didn't just translate the stone; it gave voice to three millennia of Egyptian records that had been silent for more than a millennium.

The stone has transitioned from a physical artifact to a global metaphor and a point of geopolitical friction.

The stone has transitioned from a physical artifact to a global metaphor and a point of geopolitical friction.

Today, "Rosetta Stone" is a universal idiom for any key that unlocks a difficult mystery or allows for translation between disparate systems. It is the namesake for language software and space probes (the Rosetta mission to a comet), cementing its status as the ultimate symbol of human communication and discovery.

However, its physical presence remains a source of tension. The Egyptian government has repeatedly called for its repatriation, arguing that the stone was taken under colonial duress and belongs in its country of origin. The British Museum continues to resist, viewing the stone as a "universal" object that belongs to global history rather than a single nation.

Image from Wikipedia

One possible reconstruction of the original stele

Another fragmentary example of a "donation stele", in which the Old Kingdom pharaoh Pepi II grants tax immunity to the priests of the temple of Min

Report of the arrival of the Rosetta Stone in England in The Gentleman's Magazine, 1802

Left and right sides of the Rosetta Stone, with inscriptions: (Left) "Captured in Egypt by the British Army in 1801" (Right) "Presented by King George III".

Experts inspecting the Rosetta Stone during the Second International Congress of Orientalists, held in London in 1874

Richard Porson's suggested reconstruction of the missing Greek text (1803)

Illustration depicting two columns of Demotic text and their Greek equivalent, as devised by Johan David Åkerblad in 1802

Replica of the Demotic texts

Champollion's table of hieroglyphic phonetic characters with their demotic and Coptic equivalents (1822)

A replica of the Rosetta Stone in Rashid (Rosetta), Egypt

Replica of the Rosetta Stone, displayed as the original used to be, available to touch, in what was the King's Library of the British Museum, now the Enlightenment Gallery

A giant copy of the Rosetta Stone by Joseph Kosuth in Figeac in southern France, the birthplace of Jean-François Champollion

A crowd of visitors examining the Rosetta Stone at the British Museum in 2014, now behind glass