Renaissance

The Renaissance was less a "rebirth" of ancient culture than a radical pivot toward Humanist inquiry.

The Renaissance was less a "rebirth" of ancient culture than a radical pivot toward Humanist inquiry.

While often framed as the sudden discovery of lost Greek and Roman texts, the movement was actually a fundamental shift in how people processed knowledge. Intellectuals moved away from "Scholasticism"—which focused on resolving contradictions between ancient authors and church doctrine—toward "Humanism." This new framework prioritized the study of human experience, ethics, and civic duty through the lens of grammar, rhetoric, and history.

This wasn't just an academic exercise; it changed the human self-image. By placing man at the center of the universe rather than as a mere cog in a divine hierarchy, Humanism provided the intellectual permission to explore, innovate, and challenge established authority. It effectively replaced a culture of "received wisdom" with a culture of "critical inquiry."

Concentrated wealth in Italian city-states transformed art from a religious tool into a competitive status symbol.

Concentrated wealth in Italian city-states transformed art from a religious tool into a competitive status symbol.

The Renaissance began in Florence not because of a sudden surge in talent, but because of a massive surge in disposable capital. The rise of a merchant and banking class—led by the Medici family—created a new kind of consumer. Art was no longer just an anonymous tribute to God; it became a vehicle for political branding and social prestige.

This patronage system allowed artists to function as professional intellectuals. Because wealthy families were competing for influence, they funded increasingly ambitious projects, driving a "quality arms race" that accelerated technical mastery. The artist’s workshop became a laboratory where aesthetics met social engineering, turning city-states like Florence and Venice into high-density hubs of creative output.

Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press acted as a force multiplier that turned a local Italian trend into a global revolution.

Johannes Gutenberg’s printing press acted as a force multiplier that turned a local Italian trend into a global revolution.

If the Renaissance had relied solely on hand-copied manuscripts, it likely would have remained a niche interest for the Italian elite. The introduction of the printing press around 1440 changed the physics of information. Ideas that once took years to travel across the Alps now moved in weeks, allowing the "Northern Renaissance" to develop its own distinct flavor focused on social reform and Christian piety.

The press did more than just spread books; it standardized language and democratized dissent. It created a "public sphere" where a scholar in Rotterdam could argue with a priest in Rome. This democratization of information eventually eroded the Catholic Church’s monopoly on knowledge, setting the stage for the Reformation and the scientific revolutions that followed.

The era dissolved the boundary between art and science by applying mathematical rigor to the physical world.

The era dissolved the boundary between art and science by applying mathematical rigor to the physical world.

Renaissance thinkers didn't distinguish between "creative" and "technical" pursuits. To paint a realistic figure, one had to be an anatomist; to design a cathedral, one had to be a mathematician. This synthesis led to the discovery of linear perspective, which used geometry to create the illusion of three-dimensional space on a flat surface, fundamentally changing how humans perceive reality.

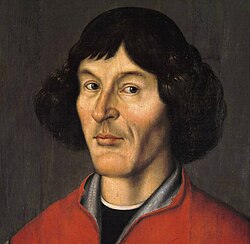

This obsession with "correct" observation served as the bridge to the Scientific Method. Leonardo da Vinci’s anatomical sketches and Copernicus’s celestial models were born from the same impulse: to look at the world directly rather than relying on ancient descriptions. By validating the evidence of the senses, the Renaissance provided the toolkit for modern science.

Modern historians view the "Dark Ages" narrative as a dramatic exaggeration designed to make the Renaissance look brighter.

Modern historians view the "Dark Ages" narrative as a dramatic exaggeration designed to make the Renaissance look brighter.

The traditional view—that the Renaissance ended a thousand-year slumber of ignorance—is largely a product of 19th-century branding. Contemporary scholars point out that the Middle Ages had several "renaissances" of their own, including the Carolingian and 12th-century revivals. The transition was a slow-burn evolution of existing medieval institutions rather than a sudden explosion of light.

Labeling the era as a "rupture" with the past was a conscious choice by Renaissance thinkers like Petrarch to distance themselves from their immediate predecessors. While the period certainly introduced revolutionary ideas, it remained deeply rooted in medieval social structures and religious fervor, proving that history rarely moves in clean, sudden breaks.

Portrait of a Young Woman (c. 1480–85) (Simonetta Vespucci) by Sandro Botticelli

View of Florence, birthplace of the Renaissance

Coluccio Salutati

A political map of the Italian Peninsula c. 1494

Pieter Bruegel's The Triumph of Death (c. 1562) reflects the social upheaval and terror that followed the plague that devastated medieval Europe.

Lorenzo de' Medici, ruler of Florence and patron of arts (portrait by Vasari)

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola, writer of the famous Oration on the Dignity of Man, which has been called the "Manifesto of the Renaissance"

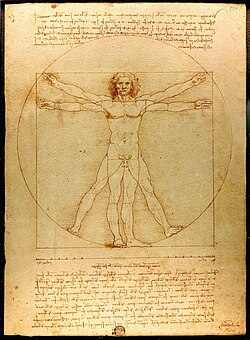

Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man (c. 1490) demonstrates the effect writers of Antiquity had on Renaissance thinkers. Based on the specifications in Vitruvius' De architectura (1st century BC), Leonardo tried to draw the perfectly proportioned man. (Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice)

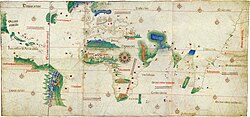

The Cantino planisphere (1502), the earliest world map detailing Portuguese maritime exploration

Anonymous portrait of Nicolaus Copernicus (c. 1580)

![Portrait of Luca Pacioli, father of accounting, painted by Jacopo de' Barbari,[f] 1495 (Museo di Capodimonte)](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2a/Pacioli.jpg/250px-Pacioli.jpg)

Portrait of Luca Pacioli, father of accounting, painted by Jacopo de' Barbari,[f] 1495 (Museo di Capodimonte)

Alexander VI, a Borgia Pope infamous for his corruption

Adoration of the Magi and Solomon adored by the Queen of Sheba from the Farnese Hours (1546) by Giulio Clovio marks the end of the Italian Renaissance of illuminated manuscript together with the Index Librorum Prohibitorum.

Leonardo Bruni

"What a piece of work is a man, how noble in reason, how infinite in faculties, in form and moving how express and admirable, in action how like an angel, in apprehension how like a god!" – from William Shakespeare's Hamlet