Last Supper

The meal transformed a Jewish fellowship dinner into the foundational ritual of Christian liturgy.

The meal transformed a Jewish fellowship dinner into the foundational ritual of Christian liturgy.

The Last Supper was the final meal shared by Jesus and his twelve apostles in Jerusalem before his crucifixion. During this gathering, Jesus performed the "Institution of the Eucharist," taking bread and wine, blessing them, and identifying them as his body and blood. This act provided the theological and structural blueprint for the Mass and Holy Communion, rituals that remain the central focus of Christian worship two millennia later.

While the meal is often associated with the Jewish Passover, its primary significance in a Christian context is the transition from old covenants to a "New Covenant." Jesus’ command to "do this in remembrance of me" shifted the focus from a commemorative meal about the Exodus to a sacrificial meal centered on his impending death and resurrection.

A fundamental chronological discrepancy exists between the Gospels regarding the meal's timing.

A fundamental chronological discrepancy exists between the Gospels regarding the meal's timing.

The Synoptic Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) explicitly describe the Last Supper as a Passover Seder, occurring on the first night of the holiday. However, the Gospel of John offers a different timeline, placing the meal a day earlier, on the "Day of Preparation." In John’s version, Jesus dies on the cross at the same time the Passover lambs are being slaughtered in the Temple, emphasizing his role as the "Lamb of God."

This "Johannine problem" has sparked centuries of debate among scholars. Some attempt to harmonize the accounts by suggesting the use of different calendars, while others argue that the discrepancy is intentional and theological. Regardless of the exact date, the meal's proximity to Passover links the themes of liberation from slavery to the Christian theme of liberation from sin.

The evening’s intimacy was shattered by the public identification of a traitor within the inner circle.

The evening’s intimacy was shattered by the public identification of a traitor within the inner circle.

The atmosphere of the meal was defined by high-stakes drama and psychological tension. According to the accounts, Jesus predicted that one of his disciples—Judas Iscariot—would betray him. This revelation triggered a wave of self-doubt among the apostles, who each asked, "Is it I, Lord?" The "sop" (a piece of bread dipped in a dish) given to Judas served as a silent, devastating confirmation of the betrayal.

Beyond Judas, the evening also highlighted the frailty of the remaining disciples. Jesus predicted that Peter, his most devoted follower, would deny knowing him three times before the next morning. These moments of human failure, occurring in the middle of a sacred ritual, characterize the Last Supper as a story of profound isolation and the collapse of a community under pressure.

Renaissance art replaced the historical reality of the meal with an enduring cultural archetype.

Renaissance art replaced the historical reality of the meal with an enduring cultural archetype.

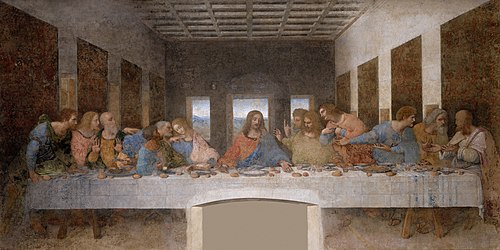

While historical Middle Eastern dining in the first century involved reclining on mats around a low U-shaped table (a triclinium), Western consciousness is dominated by Leonardo da Vinci’s "The Last Supper." Leonardo’s choice to seat everyone on one side of a long, rectangular table was a theatrical device designed to show every face and reaction, rather than a reflection of historical accuracy.

This artistic tradition fixed the "frozen moment" of the betrayal announcement in the global imagination. Leonardo’s masterpiece, along with versions by Tintoretto and Rubens, moved the event out of a cramped Jerusalem "Upper Room" and into grand, airy halls. These depictions prioritize the emotional and symbolic weight of the moment over the archaeological reality of a 1st-century Jewish meal.

The "Upper Room" remains one of the most contested sites in religious archaeology.

The "Upper Room" remains one of the most contested sites in religious archaeology.

Tradition locates the meal in the Cenacle, a room on Mount Zion in Jerusalem. However, the current structure dates largely to the Crusader era (12th century), and its history is a complex layer-cake of religious claims. It has served as a church, a mosque, and is located directly above a site traditionally revered as the Tomb of King David.

Because of this "double-decker" sanctity, the site is a flashpoint for Jewish-Christian tensions. While scholars doubt that the current room is the literal 1st-century location, the site represents a continuous tradition of pilgrimage. It serves as a physical anchor for the "Last Supper" narrative, connecting the biblical text to a specific, tangible point on the map.

The Last Supper (1495–1498). Mural, tempera on gesso, pitch and mastic, 700 x 880 cm (22.9 x 28.8 ft). In the Santa Maria delle Grazie Church, Milan, Italy, it is Leonardo da Vinci's dramatic interpretation of Jesus' last meal before death. Depictions of the Last Supper in Christian art have been undertaken by artistic masters for centuries, Leonardo da Vinci's late-1490s mural painting, being the best-known example. (Clickable image—use cursor to identify.)

Last Supper, Monreale Cathedral mosaics (Palermo, Sicily, Italy)

Jesus giving the Farewell Discourse to his eleven remaining disciples, from the Maesta by Duccio, 1308–1311

13th century Orthodox Russian icon from 1497

The Cenacle on Mount Zion, claimed to be the location of the Last Supper and Pentecost.

The Washing of Feet and the Supper, from the Maesta by Duccio, 1308–1311.

Simon Ushakov's icon of the Mystical Supper, 1685

Last Supper, Carl Bloch. In some depictions John the Apostle is placed on the right side of Jesus, some to the left.

Miniature depiction from c. 1230

Communion of the Apostles, by Fra Angelico, with donor portrait, 1440–41

Last Supper, by Jaume Huguet, c. 1470

The Last Supper, by Dieric Bouts, 1464–1468

Domenico Ghirlandaio, 1480, depicting Judas separately

Last Supper, sculpture, c. 1500

The first Eucharist, depicted by Juan de Juanes in The Last Supper, c. 1562