Great Barrier Reef

Visible from space, this 2,300-kilometer biological mega-structure is the world’s largest single entity built by living organisms.

Visible from space, this 2,300-kilometer biological mega-structure is the world’s largest single entity built by living organisms.

The Great Barrier Reef is not a singular, solid wall, but a massive mosaic of nearly 3,000 individual reefs and 900 islands stretching across 344,400 square kilometers. Located in the Coral Sea off the coast of Queensland, Australia, its total area is larger than Italy or Japan. This isn't just a geological formation; it is a living architecture created over hundreds of thousands of years by tiny coral polyps.

While the modern structure is roughly 6,000 to 8,000 years old—formed since the last Ice Age—the reef’s foundation rests on much older calcium carbonate remains. It serves as a massive offshore breakwater, protecting the Australian coastline from the heavy swells of the Pacific Ocean.

The reef functions as a global marine nursery, supporting an intensity of life that rivals the world's most dense rainforests.

The reef functions as a global marine nursery, supporting an intensity of life that rivals the world's most dense rainforests.

The ecosystem is a "biological engine" for the ocean. It hosts 1,500 species of fish, 400 types of hard coral, and one-third of the world’s soft corals. This diversity isn't just for show; the reef provides critical habitat for endangered species like the green sea turtle and the dugong. It is a vital breeding ground for humpback whales that migrate from Antarctica to give birth in the warm tropical waters.

At the heart of this productivity is a complex symbiosis between coral polyps and microscopic algae called zooxanthellae. The algae live inside the coral tissues, providing food via photosynthesis, while the coral provides the algae with a protected home and the compounds they need for energy. This relationship is the literal foundation of the entire food web.

For over 60,000 years, the reef has served as a cultural landscape deeply integrated into the identity of Australia’s First Nations peoples.

For over 60,000 years, the reef has served as a cultural landscape deeply integrated into the identity of Australia’s First Nations peoples.

Long before European "discovery," Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups managed and lived alongside the reef. To these Traditional Owners, the reef is not just a resource; it is "Sea Country," a spiritual landscape intertwined with creation stories, social structures, and ancestral history. Over 70 different Indigenous groups have historical and ongoing ties to the area.

This connection is recognized in modern management. Traditional Owners are increasingly involved in the governance of the Marine Park, blending ancient ecological knowledge with modern western science to monitor turtle populations, manage sustainable fishing, and protect sacred sites.

Anthropogenic climate change has shifted the reef from a state of resilience to a cycle of frequent, catastrophic mass-bleaching events.

Anthropogenic climate change has shifted the reef from a state of resilience to a cycle of frequent, catastrophic mass-bleaching events.

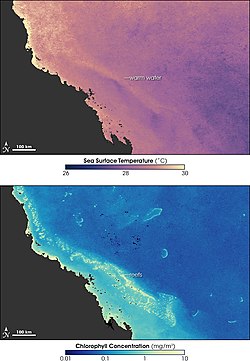

The reef is currently in a race against rising ocean temperatures. When the water gets too warm, corals become stressed and expel their symbiotic algae, turning white—a process known as bleaching. While a bleached reef isn't dead, it is "starving" and highly vulnerable. If temperatures don't drop quickly enough, the coral dies, leading to a collapse of the local ecosystem.

Since 1998, mass bleaching events have become more frequent and severe, leaving the reef less time to recover between heatwaves. Compounding this threat are crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks and agricultural runoff, which lowers water quality and makes it harder for new coral larvae to settle and grow.

As a $6 billion annual economic engine, the reef demonstrates that ecological preservation is synonymous with regional financial stability.

As a $6 billion annual economic engine, the reef demonstrates that ecological preservation is synonymous with regional financial stability.

The Great Barrier Reef is one of the world's premier tourist destinations, generating roughly $6.4 billion for the Australian economy every year. It supports over 64,000 full-time jobs, ranging from marine biologists and dive instructors to hospitality workers. For the state of Queensland, the reef is an irreplaceable asset that sustains entire coastal communities.

This creates a paradox: the reef’s fame attracts millions of visitors whose travel contributes to the carbon emissions warming the oceans. Management efforts now focus heavily on "high-value, low-impact" tourism, where a portion of every ticket sold goes directly into a reef management fund to pay for conservation and crown-of-thorns starfish control.

Image from Wikipedia

Aerial photography

Heron Island, a coral cay in the southern Great Barrier Reef

Aerial view of Arlington Reef

A variety of colourful corals on Flynn Reef near Cairns

Moore Reef

A green sea turtle on the Great Barrier Reef

A striped surgeonfish amongst the coral on Flynn Reef

Sea temperature and bleaching of the Great Barrier Reef

Crown-of-thorns starfish

The Shen Neng 1 aground on the Great Barrier Reef, 5 April 2010

Map of The Great Barrier Reef Region, World Heritage Area and Marine Park, 2014

A blue starfish (Linckia laevigata) resting on hard Acropora and Porites corals

A scuba diver looking at a giant clam on the Great Barrier Reef

Helicopter view of the reef and boats