The Communist Manifesto

Human history is driven by the friction of class struggle rather than the evolution of ideas.

Human history is driven by the friction of class struggle rather than the evolution of ideas.

The central thesis of the Manifesto is "historical materialism," the idea that society’s legal and political "superstructure" is built upon its economic "base." Marx and Engels argue that every era is defined by its mode of production—whether feudalism, antiquity, or capitalism—and that the primary engine of change is the conflict between those who own the means of production and those who provide the labor.

This perspective reframes history as a series of displacements. Just as the bourgeoisie (the merchant class) overthrew the feudal lords to establish capitalism, the authors predict that the proletariat (the working class) will inevitably overthrow the bourgeoisie. By defining social classes through their relationship to property and tools, the Manifesto turned "socialism" from a vague moral ideal into what the authors called a "scientific" inevitability.

Capitalism is a revolutionary force that "strips the veil" from social relations while creating its own "grave-diggers."

Capitalism is a revolutionary force that "strips the veil" from social relations while creating its own "grave-diggers."

The Manifesto surprisingly praises the bourgeoisie for its unprecedented productivity and its role in dissolving old, "idyllic" feudal ties. It describes capitalism as a system that must "nestle everywhere" and "settle everywhere," creating a globalized world in its own image. However, this progress comes at the cost of alienation; workers are reduced to mere "appendages of the machine," and their labor is commodified into a tool for capital accumulation.

The authors argue that capitalism contains the seeds of its own destruction. By concentrating workers in large factories and urban centers, the system inadvertently organizes and unifies the very class that will eventually revolt. This polarization—where society splits into two hostile camps—is what Marx and Engels believe makes the proletarian revolution both possible and necessary.

The document transitioned from a religious-style "catechism" to a combative, historical narrative.

The document transitioned from a religious-style "catechism" to a combative, historical narrative.

The Manifesto did not start as a soaring call to action. It began as a "Confession of Faith" written by Friedrich Engels in a question-and-answer format similar to a church catechism (e.g., "Question 1: Are you a communist? Answer: Yes"). Engels eventually realized this format lacked the "historical narrative" required for a world-changing document and urged Marx to rewrite it as a manifesto.

The writing process was fueled by intense pressure. Marx, a notorious procrastinator, spent months delivering lectures and writing articles while the Communist League waited for the draft. It was only after the League issued an ultimatum in January 1848—demanding the manuscript by February 1st—that Marx rushed to finish the final version. While Engels provided the "intellectual bank account" of ideas, the final rhetorical force and "spectre" imagery were exclusively Marx’s handiwork.

"Scientific Socialism" was forged from a blend of industrial economics and classical literature.

"Scientific Socialism" was forged from a blend of industrial economics and classical literature.

While the Manifesto is a political document, its DNA is deeply literary. Marx was a lifelong admirer of William Shakespeare, and the influence of Hamlet is evident in the famous opening: "A spectre is haunting Europe." The authors also drew on the epic imagery of John Milton and the social criticism of Thomas Carlyle, blending these high-culture influences with the "cold" logic of English and Scottish political economy.

This combination of poetic rhetoric and economic analysis was intentional. By framing the struggle of the working class through the lens of historical dialectics (derived from the philosopher Hegel), Marx and Engels sought to provide the proletariat with more than just a list of grievances; they provided a grand narrative that made their struggle appear as a fundamental law of the universe.

The Manifesto’s "Ten Points" provided a radical blueprint for the transition to a classless society.

The Manifesto’s "Ten Points" provided a radical blueprint for the transition to a classless society.

Section II of the text outlines a specific, 10-point plan for the "proletarian revolution." These measures were designed to centralize power and wealth in the hands of the state as a precursor to the eventual abolition of all classes. Key demands included the abolition of private property in land, a heavy progressive income tax, the nationalization of transport and communication, and the introduction of free public education.

The ultimate goal of these policies was a society where "the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all." While some of these points—like the elimination of child labor and the progressive tax—have been integrated into modern social democracies, others remain the most controversial and radical aspects of the Marxist program, aimed at the total dismantling of the capitalist order.

A decorative border and ornate text reading "Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei." on darker-than-white paper.

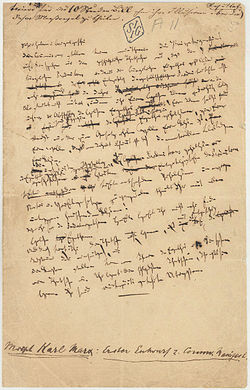

Only surviving page from the first draft of the Manifesto, handwritten by Karl Marx

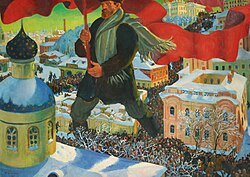

A scene from the German March 1848 Revolution in Berlin

Immediately after the Cologne Communist Trial of late 1852, the Communist League disbanded itself.

Following the 1917 October Revolution, Marx and Engels' classics like The Communist Manifesto were distributed far and wide.

Soviet Union stamp commemorating the 100th anniversary of the Manifesto