Tea

The world's most popular beverage relies on a single evergreen shrub with a 22,000-year evolutionary history.

The world's most popular beverage relies on a single evergreen shrub with a 22,000-year evolutionary history.

While we enjoy hundreds of varieties, almost all tea comes from Camellia sinensis. Genetic mapping suggests the plant originated in the borderlands of southwest China, northern Myanmar, and northeast India. The two primary varieties—the small-leaf Chinese tea and the large-leaf Assam tea—diverged roughly 22,000 years ago during the last glacial maximum.

The "botanical homeland" of tea is a compact region, yet the plant has proved remarkably adaptable. It is a biological paradox: it behaves as both a solution (water-soluble compounds like amino acids) and a suspension (physical particles) when brewed. Its stimulating effect is powered by caffeine—making up 3% of its dry weight—alongside smaller amounts of theobromine and theophylline.

Three words—Tea, Cha, and Chai—map the historical trade routes of the global economy.

Three words—Tea, Cha, and Chai—map the historical trade routes of the global economy.

Nearly every word for tea worldwide derives from a single root, and the specific version a language uses reveals how the drink arrived there. "Cha" entered English in the 1590s via the Portuguese, who traded in Macao and adopted the Cantonese pronunciation. Meanwhile, the term "Tea" arrived via the Dutch, who used the Min Chinese "tê" from their coastal trade routes.

The third form, "Chai," represents the overland Silk Road. It originated from northern Chinese pronunciations that traveled through Central Asia to Persia, picking up the Persian suffix "-yi." These linguistic markers serve as a verbal map of 16th and 17th-century globalization, distinguishing between those who traded by sea and those who traded by land.

Tea transformed from a bitter ancient soup and medicine into a refined global ritual.

Tea transformed from a bitter ancient soup and medicine into a refined global ritual.

In its earliest form, tea wasn't a drink at all; ancient East Asians ate the leaves raw, added them to soups, or fermented them to chew like areca nuts. It was initially valued as a "bitter vegetable" with medicinal properties. The shift to a recreational beverage began in earnest during the Chinese Tang Dynasty, later popularized by the 8th-century "Tea Master" Lu Yu, who wrote the first definitive treatise on the subject.

The "colors" of tea (Green, Black, Oolong, Yellow) are not the result of different plants, but different processing timelines. Green tea is unoxidized, achieved by pan-firing leaves to stop chemical changes. Oolong is partially oxidized, while Black tea—favored by Western markets for its shelf stability during long sea voyages—is fully oxidized. Yellow tea was a "happy accident," created when careless drying allowed leaves to yellow and mellow in flavor.

The British quest to break the Chinese tea monopoly redrew the maps of India and sparked global conflicts.

The British quest to break the Chinese tea monopoly redrew the maps of India and sparked global conflicts.

By the 18th century, tea was so vital to the British economy that its trade imbalances triggered wars. Because China demanded payment in silver, the British began smuggling opium into China to recover their bullion, leading directly to the Opium Wars. Simultaneously, the British government engaged in industrial espionage, sending botanist Robert Fortune on a secret mission to steal tea plants and techniques from China to establish plantations in India.

This state-sponsored pivot successfully broke the Chinese monopoly. The British discovered a native tea variety in Assam and hybridized it with Chinese plants, creating the massive tea industries of India and Sri Lanka (Ceylon). In the West, tea's high taxes even helped ignite the American Revolution via the Boston Tea Party, proving that the "dead leaves" Starkov once refused as a gift had become the world's most volatile commodity.

Image from Wikipedia

Tea plant (Camellia sinensis) from Köhler's Medicinal Plants, 1897

A 19th-century Japanese painting depicting Shennong: Chinese legends credit Shennong with the invention of tea.

Tea with ingredients, China

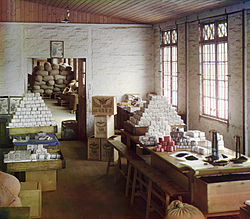

Tea-weighing station north of Batumi, Russian Empire, before 1915

The Raymond, Hugh Mckay Commander. The first vessel direct from China to Hull on her arrival on 14 October 1843 with a cargo of tea.

World map of tea exporters and importers, 1907

Fresh tea leaves in various stages of growth

Tea harvesting in Zhejiang province, China, May 1987

Tea plantations around Mattupetty lake near Munnar, India

Women picking tea in Kenya

Tea plantation near Sa Pa, Vietnam

Common processing methods of tea leaves

Teas of different levels of oxidation (L to R): green, yellow, oolong, and black

Black tea is often taken with milk.