Suprematism

Suprematism rejects the objective world to achieve the "supremacy" of pure, non-representative feeling.

Suprematism rejects the objective world to achieve the "supremacy" of pure, non-representative feeling.

Founded by Kazimir Malevich in 1913, Suprematism was the first movement to argue that art should have nothing to do with "things." While earlier abstract movements like Cubism deconstructed real-world objects, Suprematism abandoned them entirely. Malevich believed that the visual phenomena of the objective world were meaningless; the only reality worth capturing was "pure feeling," expressed through a strict grammar of squares, circles, and rectangles.

This "non-objective" approach was intended to liberate the artist from the "ideal structure of life." By stripping away the need to illustrate history, religion, or nature, Malevich sought a "desert" of liberation where art could exist for its own sake. It wasn't just a style, but a philosophical claim that the future of the universe would be built on the foundations of absolute non-objectivity.

The movement was born from a "futuristic" opera and a fascination with the fourth dimension.

The movement was born from a "futuristic" opera and a fascination with the fourth dimension.

The aesthetic roots of Suprematism lie in the 1913 opera Victory Over the Sun. Malevich designed the sets and costumes using simple geometric shapes and harsh lighting that made performers' limbs vanish into darkness. Crucially, the stage curtain featured a black square—a "zero point" that signified a new beginning for Russian art, independent of Western trajectories.

Beyond the stage, Malevich was influenced by the mystic P.D. Ouspensky, who theorized about a "fourth dimension" beyond human sensory access. This led Malevich to experiment with "non-Euclidean" geometry. His early titles, such as Two dimensional painted masses in the state of movement, suggest that his floating shapes weren't just flat decorations but snapshots of forms moving through time and higher dimensions.

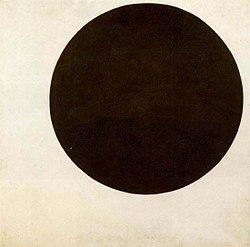

Malevich’s "Black Square" functioned as a secular icon, replacing religious imagery with a geometric zero point.

Malevich’s "Black Square" functioned as a secular icon, replacing religious imagery with a geometric zero point.

At the seminal 0.10 Exhibition in 1915, Malevich introduced the Black Square to the world. He staged it in the "red corner" of the room—the traditional place in a Russian home reserved for a religious icon. By placing a void of black paint where a saint's face should be, Malevich signaled that geometry was the new spiritual authority.

The movement progressed through three stages: the black, the colored (polychrome), and finally the white. His White on White series represented the ultimate "breakthrough" into a monochrome void. By removing even the contrast of color, he sought to reach a state of "pure exhaustion" of the object, where only the texture of paint and the essence of feeling remained.

Unlike Constructivism, which sought to engineer society, Suprematism remained aggressively anti-utilitarian.

Unlike Constructivism, which sought to engineer society, Suprematism remained aggressively anti-utilitarian.

A common mistake is to conflate Suprematism with its contemporary, Constructivism. While both used geometric shapes, they were philosophical antagonists. Constructivism viewed the artist as an "engineer" who should use art to build a functional, socialist society. It was obsessed with materials, utility, and the "cult of the object."

Suprematism, by contrast, was profoundly anti-materialist. Malevich argued that art no longer cared to serve the state or religion. While several artists (like El Lissitzky and Lyubov Popova) eventually migrated from Suprematism to Constructivism to align with the Russian Revolution's practical needs, the core of Suprematism remained a "blissful sense of liberating non-objectivity" that refused to be useful.

Visionary architects expanded Suprematist planes into three-dimensional "architectons" and floating cities.

Visionary architects expanded Suprematist planes into three-dimensional "architectons" and floating cities.

The transition from 2D painting to 3D space was led by Lazar Khidekel and El Lissitzky. Lissitzky developed "Prouns"—works he described as "the station where one changes from painting to architecture." These were not just drawings but axonometric projections that treated geometric shapes as volumetric structures.

Lazar Khidekel, the only true Suprematist architect, took this further by imagining "visionary architecture." He proposed futuristic, organic urban environments like the City on the Water (1925) and Aero-City. These designs moved away from the "pagan" triangle in favor of right angles and horizontal "architectons." This legacy persists today, notably influencing the late architect Zaha Hadid, who cited Suprematist abstraction as a primary influence on her fluid, non-objective structures.

Stalinist censorship forced the movement underground, turning radical abstraction into a forbidden language.

Stalinist censorship forced the movement underground, turning radical abstraction into a forbidden language.

As Stalinism took hold in the late 1920s, the Russian avant-garde faced harsh state criticism. By 1934, "Socialist Realism" became official policy, mandating that art be figurative and glorify the state. Radical abstraction was prohibited as "bourgeois" or "formalist."

Malevich was forced to return to traditional portraiture to survive, but he never truly abandoned his philosophy. In his 1933 self-portrait, he painted himself in a conventional, Renaissance-inspired style—but he signed the work with a tiny, hand-painted black-and-white square in the corner. It was a final, defiant act of "non-objective" loyalty in an era of enforced reality.

Image from Wikipedia

Kazimir Malevich, Black Square, 1915, oil on linen, 79.5 × 79.5 cm, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow

Malevich, Self-Portrait, 1933

Image from Wikipedia

Image from Wikipedia