Superconductivity

Superconductivity is a quantum phase transition that achieves the impossible: zero electrical resistance and the total expulsion of magnetic fields.

Superconductivity is a quantum phase transition that achieves the impossible: zero electrical resistance and the total expulsion of magnetic fields.

Unlike ordinary metals, which see a gradual decline in resistance as they cool, superconductors hit a "critical temperature" where resistance vanishes instantly and completely. An electric current inside a superconducting loop can theoretically flow forever without a power source because no energy is lost as heat. This isn't just "extremely efficient" conduction; it is a fundamental shift in how matter behaves.

Crucially, this state is defined by the Meissner effect—the active ejection of magnetic fields from the material's interior. This proves that superconductivity is not just "perfect" classical conductivity, but a distinct quantum mechanical state. If you place a magnet over a superconductor, it won't just sit there; the superconductor creates an opposing field that forces the magnet to levitate.

Microscopic harmony allows electrons to overcome their natural repulsion by pairing up through crystal vibrations.

Microscopic harmony allows electrons to overcome their natural repulsion by pairing up through crystal vibrations.

At the subatomic level, electrons usually repel each other because they share the same negative charge. However, BCS theory (named for Bardeen, Cooper, and Schrieffer) explains that in a superconductor, electrons form "Cooper pairs." They are glued together by phonons—vibrations in the material's crystal lattice. As one electron passes through the lattice, it pulls nearby positive ions toward it; this brief concentration of positive charge then attracts a second electron.

These pairs behave like a single "superfluid" that moves through the material without colliding with atoms. While this explains "conventional" superconductors, newer "unconventional" materials—like high-temperature ceramics—still baffle physicists. In these cases, the electron-pairing mechanism remains one of the most significant open questions in modern physics.

The discovery of high-temperature superconductors moved the field from expensive liquid helium to the practicality of liquid nitrogen.

The discovery of high-temperature superconductors moved the field from expensive liquid helium to the practicality of liquid nitrogen.

For decades, superconductivity was a laboratory curiosity because it required liquid helium, which boils at a frigid 4.2 K (−269 °C) and is difficult to handle. This changed in 1986 with the discovery of cuprate-perovskite ceramics. These materials could superconduct at temperatures above 90 K, allowing scientists to use liquid nitrogen as a refrigerant.

Liquid nitrogen is cheaper than milk and far easier to manage than helium, making experiments and industrial applications viable. While "high-temperature" is a relative term—these materials are still colder than any freezer on Earth—the jump to 77 K (the boiling point of nitrogen) was the catalyst that moved superconductivity into the commercial sector.

Ductile niobium alloys transformed theoretical physics into the "workhorse" technology behind modern MRI scanners.

Ductile niobium alloys transformed theoretical physics into the "workhorse" technology behind modern MRI scanners.

While exotic ceramics get the headlines, niobium-titanium is the unsung hero of the industry. Early superconductors were brittle and failed in the presence of strong magnetic fields. In the 1960s, researchers discovered that niobium alloys could maintain superconductivity while carrying massive current densities even in intense magnetic fields.

Today, these "Type II" superconductors are the primary components of MRI machines, which account for roughly 80% of the global superconductivity market. They allow for the creation of stable, incredibly powerful magnetic fields that would melt ordinary copper wires. Beyond medicine, these alloys are essential for the particle accelerators that probe the origins of the universe.

The new frontier of 2D materials allows researchers to "tune" superconductivity by simply twisting atomic layers.

The new frontier of 2D materials allows researchers to "tune" superconductivity by simply twisting atomic layers.

Recent breakthroughs in "moiré" materials have turned superconductivity into a geometry problem. By stacking two layers of graphene and twisting them to a "magic angle" (roughly 1.1 degrees), researchers can slow down electrons enough to force them into a superconducting state.

This discovery has created a "tunable" laboratory for physics. Instead of synthesizing entirely new chemical compounds, scientists can now adjust the electrical field or the twist angle of a 2D sheet to toggle between insulating and superconducting behaviors. This flexibility is a cornerstone of the burgeoning field of quantum computing and "chiral" electronics.

A high-temperature superconductor levitating above a magnet. A persistent electric current flows on the surface of the superconductor, acting to exclude the magnetic field of the magnet (Meissner effect). This current effectively forms an electromagnet that repels the magnet.

Timeline of superconducting materials. Colors represent different classes of materials: BCS (dark green circle) Heavy fermion-based (light green star) Cuprate (blue diamond) Buckminsterfullerene-based (purple inverted triangle) Carbon-allotrope (red triangle) Iron-pnictogen-based (orange square) Strontium ruthenate (grey pentagon) Nickel-based (pink six-point star)*NdNiO should read Sr0.2Nd0.8NiO2

Heike Kamerlingh Onnes (right), the discoverer of superconductivity. Paul Ehrenfest, Hendrik Lorentz, Niels Bohr stand to his left.

Top: Periodic table of superconducting elemental solids and their experimental critical temperature (T)Bottom: Periodic table of superconducting binary hydrides (0–300 GPa). Theoretical predictions indicated in blue and experimental results in red

Electric cables for accelerators at CERN. Both the massive and slim cables are rated for 12,500 A. Top: regular cables for LEP; bottom: superconductor-based cables for the LHC

Cross section of a preformed superconductor rod from the abandoned Texas Superconducting Super Collider (SSC)

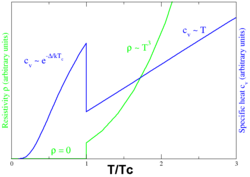

Behavior of heat capacity (cv, blue) and resistivity (ρ, green) at the superconducting phase transition

A sample of bismuth strontium calcium copper oxide (BSCCO), which is currently one of the most practical high-temperature superconductors. Notably, it does not contain rare-earths. BSCCO is a cuprate superconductor based on bismuth and strontium. Thanks to its higher operating temperature, cuprates are now becoming competitors for more ordinary niobium-based superconductors, as well as magnesium diboride superconductors.