Stellar nucleosynthesis

Stars serve as the universe's chemical factories, transforming primordial gas into the complex periodic table via nuclear fusion.

Stars serve as the universe's chemical factories, transforming primordial gas into the complex periodic table via nuclear fusion.

While the Big Bang provided the universe with its initial supply of hydrogen, helium, and lithium, every other element was forged inside a star. Stellar nucleosynthesis is the predictive theory that explains why some elements are abundant and others are rare. By plotting the chemical makeup of the solar system, scientists discovered a "sawtooth" pattern of abundances that proved the creation of matter is a systematic, non-random process driven by the life cycles of stars.

This process is not just about creating matter; it is the reason stars shine. The energy released during these nuclear reactions provides the heat and light that prevents a star from collapsing under its own gravity. Because the theory accurately estimates the observed abundances of elements we see in space today, it remains one of the most successful and foundational frameworks in modern astrophysics.

The landmark "B2FH" paper of 1957 transformed our understanding of stars from mere light sources into the architects of matter.

The landmark "B2FH" paper of 1957 transformed our understanding of stars from mere light sources into the architects of matter.

The history of this field began with Arthur Eddington in 1920, who first suggested that stars were powered by fusing hydrogen into helium. However, the full picture of how heavier elements are built didn't emerge until 1954, when Fred Hoyle described how massive stars synthesize elements from carbon to iron. This work culminated in the 1957 "B2FH" paper—named after authors Burbidge, Burbidge, Fowler, and Hoyle—which became one of the most cited papers in the history of the field.

These researchers didn't just theorize; they identified the specific "pathways" elements take. They showed how different stellar environments—from the steady burning of a middle-aged star to the violent explosion of a supernova—contribute different pieces to the periodic table. This transition from "energy generation" to "element creation" allowed scientists to determine the age of the elements and, by extension, the age of the universe itself.

A star's internal structure is dictated by a radical temperature sensitivity that determines which fusion "engine" it uses.

A star's internal structure is dictated by a radical temperature sensitivity that determines which fusion "engine" it uses.

Hydrogen fusion, or "hydrogen burning," is the primary energy source for 90% of stars. In stars the size of our Sun, the "Proton-Proton chain" is the dominant engine. It is a steady process that occurs over billions of years. However, in stars just 1.3 times more massive than the Sun, the "CNO cycle" (Carbon-Nitrogen-Oxygen) takes over. The CNO cycle is incredibly sensitive to temperature: a mere 10% increase in core heat can trigger a 350% increase in energy production.

This sensitivity creates a physical divide in star types. Smaller stars like the Sun transfer heat via radiation, keeping their cores relatively calm and unmixed. Massive stars, driven by the intense CNO cycle, develop churning "convection zones" at their centers. This internal "stirring" keeps the fusion region well-mixed with fresh fuel, fundamentally changing how the star evolves and eventually dies.

The creation of heavy elements relies on a "ceiling" at iron that can only be shattered by the violence of a supernova.

The creation of heavy elements relies on a "ceiling" at iron that can only be shattered by the violence of a supernova.

Stars build elements in a sequence: hydrogen to helium, helium to carbon, and progressively upward to silicon. However, this process hits a physical wall at iron (atomic mass 56). Fusing elements heavier than iron consumes more energy than it releases, meaning a star cannot "burn" its way into the heaviest parts of the periodic table. Instead, elements heavier than iron are created through neutron capture—processes known as the s-process (slow) and r-process (rapid).

The final distribution of these elements into the universe requires a catastrophic event. Low-mass stars gently puff out their atmospheres as planetary nebulae, but high-mass stars end in supernovas. During these explosions, a "compressional shock wave" rebounds off the star's core, raising temperatures by 50% in a single second. This "explosive nucleosynthesis" is the final epoch of a star's life, responsible for the sudden creation of the rarest and heaviest elements in existence.

Logarithmic scales plot of the relative energy output (ε) of the following fusion processes at different temperatures (T): Proton–proton chain (PP) CNO cycle Triple-α process Combined energy generation of PP and CNO within a star The Sun's core temperature (about 1.57×107 K, with l o g 10 T = 7.20 {\displaystyle log_{10}T=7.20} ), at which PP is more efficient.

In 1920, Arthur Eddington proposed that stars obtained their energy from nuclear fusion of hydrogen to form helium and also raised the possibility that the heavier elements are produced in stars.

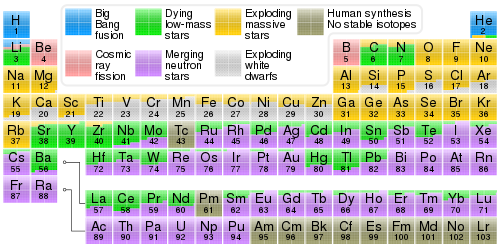

A version of the periodic table indicating the origins – including stellar nucleosynthesis – of the elements.

Proton–proton chain reaction

Image from Wikipedia