The Starry Night

Van Gogh painted his most famous night scene during the day from the confines of a mental asylum.

Van Gogh painted his most famous night scene during the day from the confines of a mental asylum.

Following the 1888 breakdown in which he mutilated his own ear, Vincent van Gogh admitted himself to the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole asylum in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence. The Starry Night was not painted outdoors under the stars, but rather from memory and sketches in a ground-floor studio during daylight hours. His view was restricted by the iron bars of his second-story bedroom window.

The painting is a "composition" rather than a literal landscape. While the hills and the prominent "Morning Star" were visible from his cell, the idyllic Dutch-style village and the towering cypress tree were products of Van Gogh’s imagination and memories of home. This blend of direct observation and internal emotion defines the shift from Impressionism to Post-Impressionism.

The "Morning Star" depicted in the swirling sky is a scientifically accurate observation of Venus.

The "Morning Star" depicted in the swirling sky is a scientifically accurate observation of Venus.

Despite the dreamlike quality of the work, astronomers have determined that Van Gogh was remarkably faithful to the celestial alignment of the spring of 1889. The brightest white "star" in the painting, located just to the right of the cypress tree, has been identified as the planet Venus. At that time, Venus was at its brightest and would have been visible as a "morning star" in the pre-dawn sky of Provence.

This accuracy suggests that even in his moments of deepest psychological distress, Van Gogh remained a disciplined observer of nature. He described the view to his brother Theo as "the morning sky from my window a long time before sunrise, with nothing but the morning star, which looked very big."

The painting's swirling patterns mirror the complex mathematics of fluid turbulence.

The painting's swirling patterns mirror the complex mathematics of fluid turbulence.

In a cross-disciplinary discovery, physicists found that the luminance distribution in The Starry Night closely matches the mathematical model of "turbulent flow." This is a notoriously difficult concept in fluid dynamics—first described by Andrey Kolmogorov in the 1940s—that explains how energy moves through swirling water or air.

Van Gogh’s brushstrokes captured the specific statistical structure of turbulence decades before science could define it. Remarkably, this "mathematical realism" only appears in the paintings he produced during periods of high mental instability; when he was calm and medicated, his work did not exhibit the same complex physical patterns.

The towering cypress tree acts as a dark bridge between the earthly and the divine.

The towering cypress tree acts as a dark bridge between the earthly and the divine.

The most dominant vertical element in the painting is the cypress tree, which Van Gogh described as "beautiful as regards lines and proportions, like an Egyptian obelisk." In the late 19th century, cypress trees were traditional symbols of mourning and death, often planted in European cemeteries.

By placing the "death" symbol (the cypress) in the foreground, reaching from the ground into the heavens, Van Gogh created a visual connection between the quiet, sleeping village and the fiery, eternal cosmos. It suggests a perspective where death is not an end, but a means of traveling to the stars—a sentiment he echoed in letters, comparing death to taking a train to a distant constellation.

Van Gogh considered the painting a "failure" that lacked individual value.

Van Gogh considered the painting a "failure" that lacked individual value.

History views The Starry Night as a masterpiece of Western art, but Van Gogh was his own harshest critic. In letters to his brother Theo, he dismissed the work as a "study" that was too stylized. He felt that the exaggerated shapes and swirls had failed to capture the "true" essence of the landscape, and he even excluded it from a list of works he thought were worth sending to art dealers.

The painting's journey to legendary status was slow. It was sold by his sister-in-law, Jo van Gogh-Bonger, in 1900 and passed through several private hands before being acquired by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1941. Today, it is arguably the most recognizable image in art history, proving that Van Gogh’s "failure" was actually the blueprint for modern expressionism.

A painting of a scene at night with 10 swirly stars, Venus, and a bright yellow crescent Moon. In the background are hills, and in the foreground a cypress tree and houses.

The Monastery of Saint-Paul de Mausole

Van Gogh's bedroom in the asylum

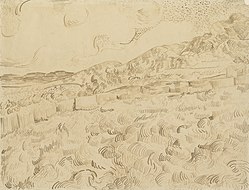

F1548 Wheatfield, Saint-Rémy de Provence, Morgan Library & Museum

F719 Green Wheat Field with Cypress, National Gallery Prague

F1547 The Enclosed Wheatfield After a Storm, Van Gogh Museum

F611 Mountainous Landscape Behind Saint-Rémy, Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek

F1541v Bird's-Eye View of the Village, Van Gogh Museum

F1541r Landscape with Cypresses, Van Gogh Museum

Van Gogh's Starry Night Over the Rhône, 1888, oil on canvas

The drawing Cypresses in Starry Night, a reed pen copy executed by Van Gogh after the painting in 1889. Originally held at Kunsthalle Bremen, today part of the disputed Baldin Collection.

Sketch of the Whirlpool Galaxy by Lord Rosse in 1845, 44 years before Van Gogh's painting

Moon

Venus

Hills and sky