Spanish Inquisition

The Inquisition shifted state violence from the battlefield to the internal regulation of the soul.

The Inquisition shifted state violence from the battlefield to the internal regulation of the soul.

Established in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs Ferdinand and Isabella, the Tribunal of the Holy Office was born in the shadow of the Reconquista—the centuries-long military campaign to reclaim Spain from Muslim rule. While the Medieval Inquisition had been under the direct control of the Pope, this new iteration was a state-run tool designed to ensure total religious orthodoxy and consolidate the power of the newly unified Spanish Crown.

The institution lasted for over 350 years, finally dissolving in 1834. During its peak, it functioned as a sophisticated bureaucratic machine that processed roughly 150,000 people. While popular culture often focuses on mass executions, modern estimates suggest 3,000 to 5,000 people were killed. The primary goal was not always death, but the total submission of the individual and the "cleansing" of the nation's spiritual landscape.

"Blood Purity" statutes transformed religious suspicion into a system of racial discrimination.

"Blood Purity" statutes transformed religious suspicion into a system of racial discrimination.

The Inquisition’s primary targets were conversos (Jews who converted to Catholicism) and moriscos (Muslims who converted). The Crown feared "Crypto-Judaism"—the secret practice of old faiths behind closed doors. This suspicion led to the 1492 Alhambra Decree, which forced Jews to either convert, leave Spain, or face death. Between 40,000 and 100,000 Jews were expelled, leading to a massive drain of commerce and culture.

This era introduced the concept of limpieza de sangre (purity of blood). It wasn't enough to be a baptized Christian; one had to prove they had no "tainted" Jewish or Muslim ancestry. This shifted the focus from belief to biology, creating a racially-based caste system that barred those with "impure" blood from holding public office or church positions. These prejudices persisted in Spanish society well into the 20th century.

The Tribunal weaponized secrecy and public theater to maintain social control through "educational" terror.

The Tribunal weaponized secrecy and public theater to maintain social control through "educational" terror.

The legal process of the Inquisition was designed to be psychologically overwhelming. Trials were conducted in secret, and the accused were rarely told who their accusers were. Inquisitors used "the grace period"—a 30-day window to self-confess—to turn neighbors and family members against one another. Torture, including the rack and waterboarding, was used not as a primary punishment, but as a procedural tool to extract confessions.

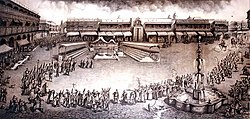

The climax of the process was the auto-da-fé (act of faith), a massive public spectacle designed to rival bullfights in popularity. These were not just executions; they were highly choreographed rituals where the accused were paraded in distinctive tunics (sambenitos), their sentences were read aloud, and they were "reconciled" or handed over to civil authorities to be burned. These events were intended to terrify the populace into compliance by making the consequences of deviance visible and inescapable.

King Ferdinand leveraged the Inquisition to seize absolute power from the Catholic Church.

King Ferdinand leveraged the Inquisition to seize absolute power from the Catholic Church.

A significant but often overlooked facet of the Inquisition was the power struggle between the Spanish Monarchy and the Papacy. Pope Sixtus IV initially authorized the Inquisition but quickly became horrified by its brutality and its use as a tool for wealth confiscation. In 1482, the Pope issued a bull condemning the Inquisition for being moved by "lust for wealth" rather than zeal for the faith.

Ferdinand effectively ignored the Pope, feigning doubt about the document's authenticity and pressuring the Vatican to relinquish control. The King eventually won, gaining the right to appoint the Inquisitor General himself. By turning the Inquisition into a branch of the government, the Spanish Crown created a legal loophole that allowed them to bypass local laws and traditional rights, effectively unifying the disparate kingdoms of Spain under a single, terrifying authority.

As the Spanish Empire expanded, the Inquisition evolved into a global moral police force.

As the Spanish Empire expanded, the Inquisition evolved into a global moral police force.

While it began with a focus on Jewish and Muslim converts, the Inquisition’s scope eventually broadened to include any perceived threat to Catholic social order. It followed Spanish conquistadors to the Americas and expanded to Southern Italy, establishing tribunals in Mexico City, Lima, and Sicily. It became a catch-all regulator for "vices," targeting Protestantism, witchcraft, blasphemy, bigamy, and Freemasonry.

By the 18th century, the Inquisition functioned less like a holy war and more like a censorship board and moral regulator. Even as the number of executions dropped, the institution remained a powerful deterrent against the Enlightenment. It wasn't until the Napoleonic Wars and the rise of liberal governance in the 19th century that the "Holy Office" was finally recognized as an anachronism and dismantled.

Coat of arms or logo

The Virgin of the Catholic Monarchs, 1491–1493. The Inquisitor, Torquemada, is behind King Ferdinand (left).

Torquemada is buried in the monastery of Saint Thomas at Ávila, and left his own epitaph: "Pestem Fugat Haereticam" i.e. "drove away the pestilence of heresy".

Burning of heretics at stakes (auto-da-fé) in a marketplace during the Spanish Inquisition.

The burning of a Dutch Anabaptist, Anneken Hendriks, who was charged with heresy in Amsterdam (1571)

Auto de fe, Plaza Mayor in Lima, Viceroyalty of Peru (17th century)

Structure of the Spanish Inquisition

Diego Mateo López Zapata in his cell before his trial by the Inquisition Court of Cuenca (engraved by Francisco Goya)

Two priests and a suspected heretic in a Spanish Inquisition interrogation chamber (Bernard Picart's engraving, 1722). In contrast to the Inquisitor's armchair, Eymeric's manual suggests that the accused be sat on a low bench.

An etching of an imagined Inquisition jail, depicting a priest overseeing a scribe as prisoners are tortured on pulleys, racks, or with torches (date unknown)

A rack on display at the Torture Museum in Toledo, Spain

An engraved depiction of water torture (1556)

In the strappado torture, the victim's hands are tied behind their back and the body is suspended by the wrists, resulting in dislocated shoulders. Weights can be added to the feet (engraving, 1768)

Rizi's 1683 painting of the 1680 auto de fe, Plaza Mayor in Madrid

Execution of Mariana de Carabajal, a converted Jew, in Mexico City, 1601