Space Shuttle Challenger disaster

A known design flaw in the solid rocket boosters turned fatal when record-low temperatures neutralized the shuttle’s primary safety seals.

A known design flaw in the solid rocket boosters turned fatal when record-low temperatures neutralized the shuttle’s primary safety seals.

The Space Shuttle’s Solid Rocket Boosters (SRBs) were not single-piece shells; they were assembled in sections using "field joints" sealed by two rubber O-rings. These rings were designed to expand and seal the gap against hot, high-pressure gases during ignition. However, testing as early as 1977 revealed that the joints actually rotated outward under pressure, pulling the seals away from their seats. By 1982, NASA had downgraded the O-rings from a "redundant" system to "Criticality 1," meaning any failure would result in the loss of the vehicle and crew.

The morning of January 28, 1986, saw record-low temperatures. The rubber O-rings lost their elasticity in the cold, becoming too stiff to expand and form a seal. While previous flights in warmer weather had shown minor O-ring "erosion" or soot bypass, the extreme cold on launch day caused a total breach. Hot gas escaped through the joint, acting like a blowtorch that burned through the attachment strut and eventually pierced the external fuel tank.

NASA leadership prioritized launch schedules over engineering warnings, creating a culture where technical concerns were suppressed.

NASA leadership prioritized launch schedules over engineering warnings, creating a culture where technical concerns were suppressed.

The disaster is a landmark case study in "groupthink" and organizational failure. On the eve of the launch, engineers from Morton Thiokol—the contractor that built the SRBs—vocalized intense concerns about the cold. They argued that they had no data to support a safe launch below 53°F (12°C). In a heated teleconference, NASA manager Lawrence Mulloy challenged these findings, famously asking if the engineers expected him to wait until April to launch. Under pressure to maintain the flight schedule, Morton Thiokol management overruled their own engineers and signed off on the launch.

Crucially, this life-or-death debate was never reported to the high-level NASA officials who made the final "go/no-go" decision. The Rogers Commission later criticized NASA’s "flawed" decision-making process, noting that the agency’s culture had shifted toward a "can-do" attitude that marginalized safety risks. Data showing the O-rings were a catastrophic risk had been available for nearly a decade, but the pattern of successful launches had created a "normalization of deviance"—the dangerous belief that because a problem hadn't caused a disaster yet, it never would.

The spacecraft did not "explode" in the traditional sense; it was torn apart by aerodynamic forces after a structural collapse.

The spacecraft did not "explode" in the traditional sense; it was torn apart by aerodynamic forces after a structural collapse.

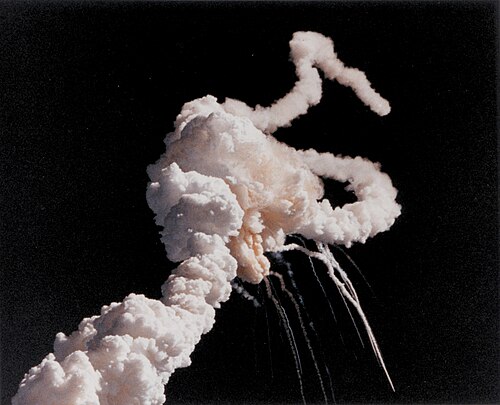

Contrary to popular belief, the Challenger did not explode into a fireball. Instead, the leak in the right SRB burned through the strut connecting it to the external tank (ET). The SRB then pivoted into the tank, causing the ET’s internal structures to collapse and release massive amounts of liquid hydrogen and oxygen. This created a massive, non-explosive flash of fire. However, the orbiter was still traveling at Mach 1.92 and was suddenly pushed broadside into the supersonic airflow.

At that speed, the aerodynamic forces were too great for the shuttle’s frame to withstand. The orbiter disintegrated 46,000 feet above the Atlantic. The crew compartment remained intact and continued on a ballistic arc, reaching a peak altitude of 65,000 feet before falling. Because the shuttle lacked an escape system, the crew survived the initial breakup but were killed when the compartment hit the ocean surface at terminal velocity. Evidence suggested that at least some crew members were conscious enough to activate their emergency air packs before impact.

The tragedy ended the era of "routine" space travel and forced a 32-month total overhaul of the program.

The tragedy ended the era of "routine" space travel and forced a 32-month total overhaul of the program.

Before Challenger, NASA had successfully branded the Space Shuttle as a safe, almost mundane vehicle capable of carrying civilians like schoolteacher Christa McAuliffe. The disaster shattered this illusion, leading to a 32-month hiatus in the program. During this time, the SRB joints were completely redesigned with a new "capture feature" to prevent rotation, and the Office of Safety, Reliability, and Quality Assurance was established to ensure that engineering concerns would never again be silenced by management.

The disaster also fundamentally changed how the U.S. used the shuttle. NASA stopped using the crewed orbiter to launch commercial satellites, shifting those payloads to uncrewed, "expendable" rockets. To replace the lost orbiter, NASA built Endeavour, which incorporated new safety features like pressurized suits for the crew during ascent. While the program eventually resumed, the "Teacher in Space" program was suspended for decades, and the agency adopted a far more conservative approach to risk management.

Image from Wikipedia

Space Shuttle Challenger – assembled for launch along with the ET and two SRBs – atop a crawler-transporter en route to the launch pad about one month before the disaster

Cross-sectional diagram of the original SRB field joint. The top end of the lower rocket segment has a deep U-shaped cavity, or clevis, along its circumference. The bottom end of the top segment extends to form a tang that fits snugly into the clevis of the bottom segment. Two parallel grooves near the top of the clevis inner branch hold ~20 foot (6 meter) diameter O-rings that seal the gap between the tang and the clevis, keeping hot gases out of the gap.

STS-51-L crew: (back) Onizuka, McAuliffe, Jarvis, Resnik; (front) Smith, Scobee, McNair.

Ice on the launch tower hours before Challenger launch

Gray smoke escaping from the right-side solid rocket booster

Plume on right SRB at T+58.788 seconds

Jay Greene after Challenger's breakup

The forward section of the fuselage after breakup, indicated by the arrow

Right SRB debris showing the hole caused by the plume

President Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan (left) at the memorial service on January 31, 1986

Members of the Rogers Commission arrive at Kennedy Space Center

Fragment of Challenger's fuselage on display at the Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex

The tribute poster of Challenger