Salem witch trials

A "disease of astonishment" among young girls sparked a lethal hunt for the supernatural.

A "disease of astonishment" among young girls sparked a lethal hunt for the supernatural.

The crisis began in February 1692 when 9-year-old Betty Parris and 11-year-old Abigail Williams began exhibiting "fits" that defied medical explanation. They screamed, threw objects, and contorted their bodies into strange positions—symptoms that locals quickly branded as "the disease of astonishment." These behaviors weren't observed in a vacuum; they mirrored accounts in popular pamphlets of the time, such as those by Cotton Mather, which described similar "bewitchments" in Boston just years prior.

The girls accused three local women of causing their physical and mental distress through witchcraft. This concept of "affliction" became the primary engine of the trials. Because the harm was invisible to everyone except the victims, the legal system relied on "spectral evidence"—the claim that a person's spirit (or "shape") was attacking the victim, even if their physical body was elsewhere.

The trials were fueled by a precarious cocktail of frontier wars, lost political identity, and religious paranoia.

The trials were fueled by a precarious cocktail of frontier wars, lost political identity, and religious paranoia.

Salem was not just a pious village; it was a community under extreme stress. The Massachusetts Bay Colony had recently lost its original Royal Charter, leaving the government in a state of legal limbo without a clear constitutional authority. Simultaneously, a brutal frontier conflict known as King William’s War was raging. Displaced refugees were flooding into Essex County, bringing with them trauma and a pervasive fear of "invisible" enemies.

Inside Salem Village, the atmosphere was equally toxic. The community was famously "quarrelsome," divided by bitter disputes over property lines, grazing rights, and the controversial leadership of Reverend Samuel Parris. Parris, who demanded the deed to the parsonage and used the pulpit to punish his detractors, acted as a catalyst for the tension. In this high-pressure environment, witchcraft accusations became a convenient tool for settling old grudges.

Puritan theology viewed women’s bodies as "porous gateways" for the Devil.

Puritan theology viewed women’s bodies as "porous gateways" for the Devil.

While men were among the accused, roughly 78% of those prosecuted were women. Puritan culture held a dualistic view: while men and women were equal in the eyes of God, they were not equal in the eyes of the Devil. Women were viewed as inherently weaker and more susceptible to temptation. Their souls were seen as unprotected in their "vulnerable bodies," making them the logical targets for demonic recruitment.

Non-conformity was the quickest path to an accusation. Women who were unmarried, childless, or "disagreeable"—like the Irish Catholic Goody Glover or the impoverished Sarah Good—were targeted first. Ironically, the legal system created a perverse incentive: because the Puritans believed a true witch would never repent, those who confessed to witchcraft were often spared and reintegrated, while those who maintained their innocence were sent to the gallows.

The crisis collapsed only when "spectral evidence" became a threat to the colony's elite.

The crisis collapsed only when "spectral evidence" became a threat to the colony's elite.

The madness ended not because the belief in witches vanished, but because the net of accusation grew too wide. As the number of accused passed 200, the "afflicted" girls began naming prominent citizens and even the wives of high-ranking officials. This prompted leading clergymen to question the validity of spectral evidence, arguing it was better that ten suspected witches escape than one innocent person be condemned.

The human toll was devastating: 19 people were hanged at Proctor's Ledge, and one man, 81-year-old Giles Corey, was pressed to death with heavy stones after refusing to enter a plea. At least five others died in the squalor of the colonial jails. By 1702, the General Court declared the trials unlawful, and in 1711, the colony reversed the attainders of the victims, though it took until 2022 to officially exonerate the last convicted "witch," Elizabeth Johnson Jr.

The Salem "outburst" shattered the New England theocracy and became a permanent American cautionary tale.

The Salem "outburst" shattered the New England theocracy and became a permanent American cautionary tale.

Historians often view the trials as the "rock on which the theocracy shattered." The fallout from the judicial murders destroyed the political influence of the Puritan clergy and paved the way for a more secular legal system that prioritized due process over religious dogma. It served as a grim lesson in the dangers of isolationism and the fragility of justice during times of mass hysteria.

Today, the events are preserved through both physical memorials and cultural metaphors. In 2016, the "Gallows Hill Project" finally confirmed the exact site of the executions at Proctor's Ledge—a rocky outcrop, not a hilltop. The trials remain the deadliest witch hunt in North American history, standing as a vivid warning against the "lethal mix of religious extremism and false accusation."

Image from Wikipedia

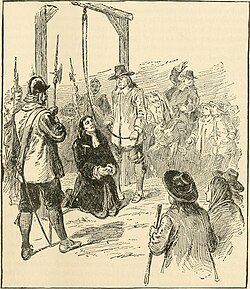

Two alleged witches being accused in the Salem witch trials, 1892 engraving

1688 portrait of Increase Mather by Joan van der Spriet

A map of Salem Village, 1692, and Salem Town at the lower-right

Reverend Cotton Mather

The parsonage in Salem Village, as photographed in the late 19th century

The present-day archaeological site of the Salem Village parsonage

Illustration of Tituba by John W. Ehninger, 1902

Magistrate Samuel Sewall

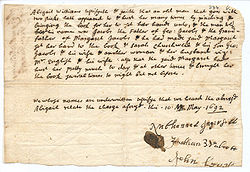

The deposition of Abigail Williams v. George Jacobs, Sr.

Statements of innocence, Part of the memorial for the victims of the 1692 witchcraft trials, Danvers, Massachusetts

Chief Magistrate William Stoughton

Illustration of the execution of George Burroughs by Henry Davenport Northrop, 1901

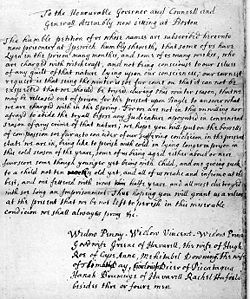

Petition for bail of eleven accused people from Ipswich, 1692

The personal seal of William Stoughton on the warrant for the execution of Bridget Bishop