Rwandan genocide

Colonial ID cards transformed a fluid class system into a rigid, racialized death trap.

Colonial ID cards transformed a fluid class system into a rigid, racialized death trap.

Before European arrival, the distinction between Hutu and Tutsi was primarily one of class and occupation—Tutsi were cattle herders and Hutu were farmers. They shared the same language, religion, and culture. While the Tutsi monarchy exercised power, the social boundaries were permeable; a wealthy Hutu could even become an "honorary Tutsi."

This fluidity was destroyed in the 1930s when Belgian colonists introduced compulsory identity cards. Influenced by the "Hamitic Hypothesis"—the pseudoscientific belief that Tutsis were a superior race from Ethiopia—the Belgians codified ethnicity into fixed categories. By making socio-economic status hereditary and mandatory, the colonial administration built the administrative framework that would later allow killers to identify their victims with surgical precision.

The 1994 slaughter was the violent climax of a civil war that had simmered for decades.

The 1994 slaughter was the violent climax of a civil war that had simmered for decades.

The genocide did not emerge from a vacuum; it was the final, desperate move of a Hutu-led government losing its grip on power. Following a 1959 revolution that overthrew the Tutsi monarchy, hundreds of thousands of Tutsis fled to neighboring countries. In 1990, these exiles—organized as the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) and led by Paul Kagame—invaded Rwanda to demand the right of return and a share in government.

While the 1993 Arusha Accords briefly promised a peaceful power-sharing transition, Hutu extremists (the Akazu) viewed any concession as an existential threat. When President Juvénal Habyarimana’s plane was shot down on April 6, 1994, these hardliners seized the resulting power vacuum to launch a pre-planned "final solution" to eliminate the Tutsi minority and the Hutu moderates who supported the peace process.

Hutu Power extremists used "mirror politics" and propaganda to weaponize the civilian population.

Hutu Power extremists used "mirror politics" and propaganda to weaponize the civilian population.

The genocide was unique for its "intimate" nature—much of the killing was done by ordinary people against their own neighbors. This was achieved through years of psychological priming by the Hutu Power movement. Extremists used the Kangura magazine and radio broadcasts to spread the "Hutu Ten Commandments," a racist manifesto that labeled any Hutu who married or befriended a Tutsi as a traitor.

Central to this effort was "accusation in a mirror"—a propaganda technique where the aggressor accuses the victim of planning the very atrocities the aggressor is about to commit. By framing the genocide as a "pre-emptive strike" against a supposed Tutsi plot to enslave Hutus, the regime turned murder into a perceived act of self-defense. This climate of fear fueled a 100-day spasm of violence that claimed between 500,000 and 1,000,000 lives.

The RPF victory stopped the killing in Rwanda but exported the instability into the Congo.

The RPF victory stopped the killing in Rwanda but exported the instability into the Congo.

The genocide ended not through international intervention—which famously failed to materialize—but through a decisive military victory by the RPF. As Kagame’s forces captured Kigali and seized government territory, the génocidaires and millions of Hutu refugees fled across the border into Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo).

This mass exodus fundamentally reshaped Central Africa. The presence of armed militias in refugee camps led directly to the First Congo War in 1996 and initiated a cycle of regional conflict that has persisted for decades. Within Rwanda, the post-genocide government has maintained stability through strict "anti-divisionism" laws, though critics argue these measures are sometimes used to suppress legitimate political dissent.

Image from Wikipedia

Rwandan genocide memorial in Geneva, Switzerland

Tutsi murdered by Hutu militia in January 1964

Paul Kagame, commander of the Rwandan Patriotic Front for most of the Civil War

Juvénal Habyarimana in 1980

Over 5,000 people seeking refuge in Ntarama church were killed by grenade, machete, rifle, or burnt alive.

Rwanda was divided into 11 prefectures and 145 communes in 1994.

Impact of the genocide on average life expectancy

Skulls and other bones kept at Murambi Technical School

Photographs of genocide victims displayed at the Genocide Memorial Center in Kigali

Map showing the advance of the RPF during the Rwandan genocide of 1994

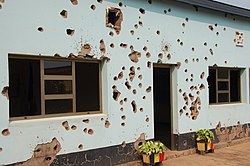

The building in which ten Belgian UNAMIR soldiers were massacred and mutilated. Today the site is preserved as a memorial for the soldiers.

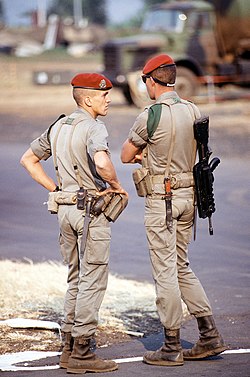

French marine parachutists stand guard at the airport, August 1994.

Convoy of American military vehicles bring fresh water from Goma to Rwandan refugees located at camp Kimbumba, Zaire in August 1994.

A memorial in a Catholic Church