Romanticism

Romanticism was a visceral rebellion against the cold rationality of the Enlightenment and the "soulless" machinery of the Industrial Revolution.

Romanticism was a visceral rebellion against the cold rationality of the Enlightenment and the "soulless" machinery of the Industrial Revolution.

The movement arose in the late 18th century as a defense of the human spirit. While the Age of Enlightenment sought to map the world through reason and the Industrial Revolution began to mechanize society, Romanticists argued that these forces were alienating and "disenchanting" nature. They viewed the rise of urbanization and economic materialism as a form of environmental and social degradation.

In response, they looked backward and inward. They idealized the Middle Ages as a "nobler" era of chivalry and organic living, deliberately contrasting it with the soot-stained reality of 19th-century factories. To a Romantic, the world was not a machine to be understood, but a mystery to be felt.

The movement redefined the artist as a "heroic genius" whose internal emotions dictated their own laws of reality.

The movement redefined the artist as a "heroic genius" whose internal emotions dictated their own laws of reality.

Before Romanticism, art often followed strict classical forms and social conventions. Romanticists flipped this, placing "romantic originality" at the center of the creative process. They believed that true art should be created ex nihilo—from nothing—rather than by following existing models. Figures like William Wordsworth described poetry as the "spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings," suggesting that the artist’s internal state was the only authentic source of truth.

This shift transformed the artist from a mere craftsman into a cultural leader or "hero." The poet Percy Bysshe Shelley famously called poets the "unacknowledged legislators of the world." This emphasis on the unique, individual voice created the modern concept of the auteur, influencing everything from 19th-century painting to 21st-century filmmaking.

Romantics prioritized the "Sublime" over the "Beautiful," seeking out experiences of awe, terror, and the untamed power of nature.

Romantics prioritized the "Sublime" over the "Beautiful," seeking out experiences of awe, terror, and the untamed power of nature.

While "beauty" was traditionally associated with order and harmony, the Romantics were fascinated by the "Sublime"—experiences that were overwhelming, dangerous, or incomprehensibly vast. They were drawn to the supernatural, the exotic, and the "wildness" of nature that humans could not control. This wasn't just an aesthetic choice; it was a spiritual one, intended to provoke a "shivering" of the soul.

This reverence for the natural world had a lasting political impact. By arguing that nature was a source of human insight and emotional health, the Romantics provided the philosophical foundation for modern environmentalism and nature conservation. They believed that breaking away from society to encounter the wilderness was necessary for human sanity.

By disrupting the concept of "objective truth," Romanticism paved the way for both modern individualism and 20th-century nationalism.

By disrupting the concept of "objective truth," Romanticism paved the way for both modern individualism and 20th-century nationalism.

Philosophically, Romanticism was a "Counter-Enlightenment." By prioritizing intuition and "inner goals" over universal reason, it began to dissolve the Western tradition of agreed-upon values. Historian Isaiah Berlin argued that this shift toward "authenticity" meant that the sincerity of a pursuit became more important than whether the goal was objectively "right."

This had a double-edged legacy. On one hand, it fueled the rise of modern liberalism and the celebration of the individual. On the other, it fueled radical nationalism; if a "nation" felt a certain destiny or identity was "authentic" to its spirit, that feeling could override universal moral laws. This "passionate self-assertion" helped shape the political landscape of the modern world.

Though it peaked in the mid-1800s, Romanticism lives on as the dominant emotional language of modern pop culture and cinema.

Though it peaked in the mid-1800s, Romanticism lives on as the dominant emotional language of modern pop culture and cinema.

Romanticism officially "dispersed" around the time of World War I, as the horrors of modern warfare made the movement’s heroic ideals seem like anachronisms. However, the movement never truly died; it simply moved into new media. The "lush" orchestral style of the Romantic era became the standard for the Golden Age of Hollywood, and most modern film scores still rely on Romantic musical cues to trigger specific emotional responses.

Furthermore, the modern act of "romanticizing" the past or our own lives—focusing on the aesthetic and emotional over the practical—is a direct inheritance from this era. Whether in speculative fiction, political rhetoric, or environmental activism, we still operate within the framework of the Romantic belief that feeling is the ultimate form of understanding.

Caspar David Friedrich, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog, 1818

Eugène Delacroix, Death of Sardanapalus, 1827, taking its Orientalist subject from a play by Lord Byron

Philipp Otto Runge, The Morning, 1808

William Blake, The Little Girl Found, from Songs of Innocence and Experience, 1794

John William Waterhouse, The Lady of Shalott, 1888, after a poem by Tennyson

Henry Wallis, The Death of Chatterton 1856, by suicide at 17 in 1770

Title page of Volume III of Des Knaben Wunderhorn, 1808

William Wordsworth (pictured) and Samuel Taylor Coleridge helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature in 1798 with their joint publication Lyrical Ballads.

Portrait of Lord Byron by Thomas Phillips, c. 1813. The Byronic hero first reached the wider public in Byron's semi-autobiographical epic narrative poem Childe Harold's Pilgrimage (1812–1818).

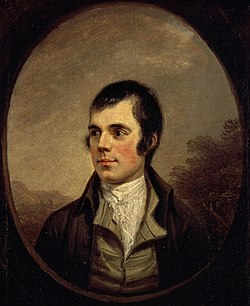

Robert Burns in Alexander Nasmyth's portrait of 1787

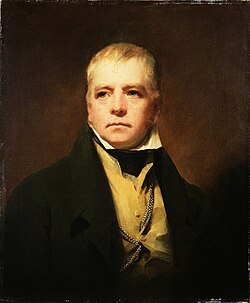

Raeburn's portrait of Walter Scott in 1822

The "battle of Hernani" was fought nightly at the theatre in 1830: lithograph, by J. J. Grandville

Adam Mickiewicz on the Ayu-Dag, by Walenty Wańkowicz, 1828

Juliusz Słowacki, a Polish poet considered one of the "Three National Bards" of Polish literature—a major figure in the Polish Romantic period, and the father of modern Polish drama.

El escritor José de Espronceda, portrait by Antonio María Esquivel (c. 1845) (Museo del Prado, Madrid)