Rice

Asian rice stems from a single domestication event in China, later colonizing every continent via trade and migration.

Asian rice stems from a single domestication event in China, later colonizing every continent via trade and migration.

While there are two distinct species of cultivated rice—Oryza sativa (Asian) and Oryza glaberrima (African)—it is the Asian variety that dominates global diets. Genetic evidence points to a single domestication event of O. sativa along the Yangtze River roughly 9,000 to 13,500 years ago. From this single origin, the crop split into indica and japonica types, eventually spreading through Austronesian migrations to Southeast Asia and via the Columbian Exchange to the Americas.

African rice followed a separate, independent path, domesticated about 3,000 years ago. Although it is now less common, it remains a resilient part of the agricultural landscape. Today, rice is so deeply embedded in human culture that it serves as the primary caloric engine for over half the world’s population, trailing only sugarcane and maize in total global production.

Rice variety is dictated by starch chemistry, separating dry, fluffy grains from sticky, cohesive textures.

Rice variety is dictated by starch chemistry, separating dry, fluffy grains from sticky, cohesive textures.

The culinary "personality" of rice—whether it stays separate or clumps together—is determined by the ratio of two starch components: amylose and amylopectin. Long-grain indica varieties (like Basmati) are high in amylose, resulting in firm, distinct grains after cooking. In contrast, short-grain japonica varieties are high in amylopectin, creating the sticky, glue-like texture essential for sushi, mochi, and risotto.

Beyond texture, processing transforms the grain's nutritional profile. Brown rice retains the bran and germ, offering more fiber but a shorter shelf life. White rice is polished for longevity and speed of cooking, though this removes many vitamins. To combat "hidden hunger," scientists developed Golden Rice through genetic engineering to synthesize beta-carotene, aiming to solve Vitamin A deficiencies in developing nations.

Rice is a hyper-local global staple where 90% is grown in Asia, but only 8% enters international trade.

Rice is a hyper-local global staple where 90% is grown in Asia, but only 8% enters international trade.

Unlike wheat or maize, which are traded heavily on global markets, rice is primarily consumed within the country where it is grown. China and India produce over half the world's 800 million tons, yet the vast majority of this stays within their borders to ensure domestic food security. This makes the global rice market highly sensitive to local shocks; when major exporters like India or Vietnam restrict trade, global prices can spike rapidly.

A significant hurdle to food security is "post-harvest loss." In developing nations, poor transport and traditional storage methods (like rural sheds) result in massive waste due to mold, rodents, and insects. In Nigeria, nearly a quarter of the crop is lost after the harvest. Transitioning from rural household storage to modern metal silos can reduce these losses from over 10% to just 0.2%.

Traditional flooding is a double-edged sword that provides pest control but generates significant methane.

Traditional flooding is a double-edged sword that provides pest control but generates significant methane.

Most rice is grown in "paddy" fields, which are flooded to a depth of a few centimeters. This water isn't just for hydration; it acts as a natural weed suppressant and protects the plants from temperature swings. However, this standing water creates an anaerobic (oxygen-free) environment where bacteria ferment organic matter, releasing methane—a potent greenhouse gas. In 2022, rice cultivation accounted for roughly 1.2% of all global greenhouse gas emissions.

To modernize this, agronomists are pushing "alternate wetting and drying" (AWD). By allowing the water level to drop below the soil surface before re-flooding, farmers can cut methane emissions by up to 90% and save water without sacrificing yield. This shift is critical as climate change threatens the status quo: global rice yields are projected to drop by about 3.2% for every 1°C of temperature rise.

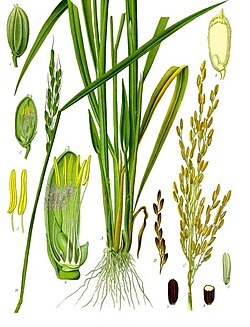

Rice plant (Oryza sativa) with branched panicles containing many grains on each stem

Rice grains of different varieties at the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI)

Anatomy of rice flowers: spikelet (left), plant with tillers (centre), caryopsis (top right), panicle (right)

Detail of rice plant showing flowers grouped in panicle. Male anthers protrude into the air where they can disperse their pollen.

Ploughing a rice terrace with water buffaloes in Java

Rice combine harvester in Chiba Prefecture, Japan

Bas-relief of 9th century Borobudur in Indonesia describes rice barns and rice plants infested by mice.

Rice production

World production of primary crops by main commodities

Production of rice

Unmilled to milled Japanese rice, from left to right, brown rice, rice with germ, white rice

Scientists measuring the greenhouse gas emissions of rice

Chinese rice grasshopper (Oxya chinensis)

Healthy rice (left) and rice with rice blast

A farmer grazes his ducks in paddy fields, Central Java