Refrigeration

Refrigeration is the active removal of heat, turning energy transfer into a tool for precise environmental control.

Refrigeration is the active removal of heat, turning energy transfer into a tool for precise environmental control.

While we often think of cooling as "adding cold," it is physically the process of removing thermal energy from a low-temperature space and rejecting it into a higher-temperature one. This "work" is traditionally mechanical—driven by compressors—but it can also be achieved through magnetism, electricity, or even lasers. It is an artificial intervention that maintains a system below the ambient temperature of its surroundings.

This technology is the backbone of the "cold chain," a seamless temperature-controlled supply line. While its most visible forms are household refrigerators and air conditioning, it also powers cryogenics and industrial freezers. Heat pumps, which provide both heating and cooling, are essentially reversible refrigeration units, proving that the technology is less about "cold" and more about the sophisticated management of energy flow.

Modern urbanization and global nutrition depend on a "cold chain" that made inhospitable climates habitable.

Modern urbanization and global nutrition depend on a "cold chain" that made inhospitable climates habitable.

The ability to control temperature fundamentally altered where and how humans live. Large cities like Houston, Texas, and Las Vegas, Nevada, thrive in regions once considered too inhospitable for dense settlement. Beyond comfort, these cities are biologically dependent on refrigeration; their food systems rely on supermarkets that can store perishables for daily consumption, a feat impossible before the 20th century.

This shift has consolidated the agricultural industry. Instead of many local, seasonal farms, refrigeration allows a small percentage of large-scale farms to supply entire populations year-round. This has drastically improved global nutrition by making diverse food sources available regardless of geography or season, though it has also made modern society entirely reliant on the continuous operation of the cooling infrastructure.

Before the machine age, an "ice trade" turned frozen New England lakes into a global mass-market commodity.

Before the machine age, an "ice trade" turned frozen New England lakes into a global mass-market commodity.

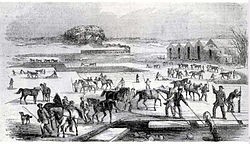

Long before mechanical compressors, refrigeration was a logistical feat of harvesting and insulation. In the early 19th century, "Ice King" Frederic Tudor transformed frozen water from New England into a luxury export for the Caribbean and the American South. By improving ship insulation and building massive icehouses, Tudor cut ice wastage from 66% to just 8%, proving that "cold" could be shipped across the globe as a product.

By the 1830s, ice had transitioned from a luxury to a mass-market staple. As the price plummeted from six cents to half a cent per pound, a "cooling culture" emerged. Families began using iceboxes to store dairy, fish, and produce, fundamentally changing the domestic kitchen. This cultural shift—getting people used to the idea of "owning" cold—paved the commercial way for the mechanical refrigerators that would eventually replace the ice man.

The leap from scientific curiosity to practical cooling required taming volatile chemicals and the physics of evaporation.

The leap from scientific curiosity to practical cooling required taming volatile chemicals and the physics of evaporation.

The quest for artificial cold began in 1755 when William Cullen used a vacuum to boil diethyl ether, observing that the evaporation absorbed heat from the air. Benjamin Franklin even experimented with this, noting that evaporating volatile liquids could lower a thermometer to −14 °C on a warm day. However, these were laboratory tricks without a mechanism to capture and reuse the cooling agent.

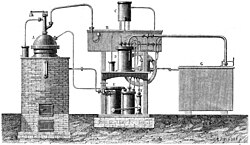

The breakthrough came with "closed-cycle" systems, which allowed volatile fluids to be condensed and reused without waste. In 1834, Jacob Perkins built the first working vapor-compression system. Later, innovators like James Harrison and Carl von Linde refined these machines using ammonia and sulfur dioxide, moving refrigeration out of the lab and into breweries and meat-packing houses, where the demand for year-round production provided the necessary capital for industrialization.

Industrialized cooling turned regional surpluses into global commodities by launching the era of refrigerated shipping.

Industrialized cooling turned regional surpluses into global commodities by launching the era of refrigerated shipping.

The final frontier for refrigeration was the ocean. In the late 19th century, countries like New Zealand and Australia had a massive surplus of meat but no way to get it to the hungry markets of Great Britain without it rotting. In 1882, the ship Dunedin successfully transported a cargo of frozen beef and mutton across the world, a feat The Times described as a "triumph over physical difficulties" that had previously been unimaginable.

This success sparked a global meat and dairy boom. It allowed South America and Australasia to become the "breadbaskets" (and butcher shops) for Europe. By the turn of the 20th century, the ability to "freeze time" via temperature control had effectively erased the distance between the world's producers and its consumers, creating the first truly global food market.

Commercial refrigeration

Ice harvesting in Massachusetts, 1852, showing the railroad line in the background, used to transport the ice.

William Cullen, the first to conduct experiments into artificial refrigeration.

Ferdinand Carré's ice-making device

Icemaker Patent by Andrew Muhl, dated December 12, 1871.

Dunedin, the first commercially successful refrigerated ship.

An early example of the consumerization of mechanical refrigeration that began in the early 20th century. The refrigerant was sulfur dioxide.

A modern home refrigerator

Figure 1: Vapor compression refrigeration

Figure 2: Temperature–Entropy diagram