Pyramid

The pyramid’s geometry is a physical "cheat code" for achieving extreme height with stone alone.

The pyramid’s geometry is a physical "cheat code" for achieving extreme height with stone alone.

Before the invention of steel skeletons, the pyramid was the only way to build toward the clouds. Because the weight of the structure is concentrated at the base and tapers toward the top, the center of gravity is exceptionally low. This makes it naturally resistant to collapse and seismic activity, allowing ancient engineers to stack millions of tons of stone without the structure crushing itself under its own weight.

In terms of material physics, a pyramid is essentially a man-made mountain. While a vertical wall requires precise internal reinforcement to stay upright, a pyramid’s mass is self-supporting. This inherent stability is why pyramids are the oldest surviving "super-tall" structures on Earth; they are the most efficient way to turn raw mass into vertical monuments.

Egypt transformed the pyramid from a simple burial mound into a high-precision "resurrection machine."

Egypt transformed the pyramid from a simple burial mound into a high-precision "resurrection machine."

While Egyptian pyramids are famous as tombs, they were designed as spiritual launchpads. The transition from the flat-topped "mastaba" to the "Step Pyramid" of Djoser reflected a theological shift: the stairs were literally intended to help the pharaoh’s soul ascend to the sun god. By the time of the Great Pyramid of Giza, the sides were smoothed into the "benben" shape, mimicking the diverging rays of the sun.

The precision of these structures remains a high-water mark for human logistics. The Great Pyramid was the tallest man-made structure for over 3,800 years, aligned to true north with an accuracy that rivals modern GPS-guided construction. It wasn't just a pile of rocks; it was a massive limestone machine calibrated to ensure the eternal life of the state by preserving its divine ruler.

Ancient civilizations across the globe "discovered" the pyramid through convergent evolution, not cultural contact.

Ancient civilizations across the globe "discovered" the pyramid through convergent evolution, not cultural contact.

Pyramids appear in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Sudan, China, and the Americas not because these cultures met, but because the pyramid is a universal solution for monumental permanence. If you want to build something that lasts forever using only gravity and stone, you eventually arrive at the pyramid.

The variations, however, reveal the unique priorities of each culture. Sudan (Nubia) has more pyramids than Egypt, but they are smaller and much steeper, functioning as narrow tomb markers for royalty. In China, pyramids were often flat-topped earthworks, functioning as massive mausoleums that were camouflaged by vegetation to resemble natural hills, blending the emperor's power with the landscape.

Mesoamerican pyramids functioned as public theaters rather than private vaults.

Mesoamerican pyramids functioned as public theaters rather than private vaults.

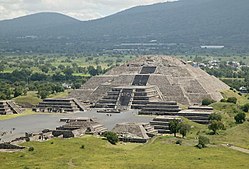

Unlike the Egyptian pyramids, which were largely "closed" systems meant to keep people out, the pyramids of the Maya, Aztecs, and Teotihuacan were "open" platforms meant to draw the eye upward. They were essentially outdoor stages. The flat tops held temples where priests performed rituals—including sacrifices—in full view of the populace below.

These structures were often built in layers, like Russian nesting dolls. Successive rulers would build a new, larger pyramid directly over the old one to signal their superior power. This "superposition" means that many Mesoamerican pyramids contain older, perfectly preserved temples deep within their cores, acting as a physical record of a city’s dynastic history.

Modern architecture uses the pyramid shape to solve for light and aesthetics rather than structural weight.

Modern architecture uses the pyramid shape to solve for light and aesthetics rather than structural weight.

In the modern era, the pyramid has been decoupled from its ancient role as a mass-heavy tomb. Architects now use the shape to maximize light and manage air volume. The Louvre Pyramid in Paris uses the geometry to create a transparent grand entrance that doesn't obstruct the view of the historic palace, while the Luxor in Las Vegas uses the hollow interior to create one of the world’s largest open atriums.

The "Transamerica Pyramid" in San Francisco highlights a different modern advantage: the tapering shape allows more sunlight to reach the street level and reduces the "wind tunnel" effect common with rectangular skyscrapers. We no longer need the pyramid shape to keep a building from falling down, but we still use it to make the built environment feel more human and accessible.

Pyramid of Khafre, Egypt, built c. 2600 BC

Prasat Thom temple at Koh Ker, Cambodia

Anu ziggurat and White Temple at Uruk

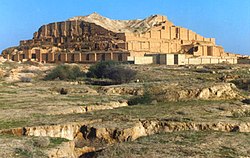

Chogha Zanbil is an ancient Elamite complex in the Khuzestan province of Iran.

The pyramids of the Giza necropolis, as seen from the air

Pyramids at Meroe with pylon-like entrances

Nubian pyramids at archaeological sites of the Island of Meroe

Pyramid of Hellinikon

Pyramids of Güímar, Tenerife, Spain

Pyramid of Cestius in Rome, Italy

Pyramid of the Moon, Teotihuacan, built between 100 and 450 AD

El Castillo at Chichen Itza

A diagram showing the various components of Eastern North American platform mounds

Monks Mound, Cahokia

Ancient Korean tomb in Ji'an, Northeastern China