Prohibition in the United States

A shift in American morality transformed alcohol from a "God-given gift" into a social disease.

A shift in American morality transformed alcohol from a "God-given gift" into a social disease.

In colonial America, alcohol was a staple of daily life, and drunkenness was viewed as a personal failure of character rather than a fault of the substance itself. This changed in the late 18th century when physician Benjamin Rush began labeling excessive drinking as a psychological disease. By the mid-1800s, this medical view merged with a religious crusade led by "pietistic" Protestants who saw the saloon as the epicenter of domestic violence and political corruption.

This "dry" sentiment was fueled by a unique "Do Everything" doctrine, notably by the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. They didn't just want to stop drinking; they saw Prohibition as a gateway to broader social progress, including prison reform and labor laws. For these reformers, removing alcohol was the primary lever for "healing" a broken society and protecting the sanctity of the home.

Prohibition was a cultural war that pitted rural Protestant values against urban immigrant traditions.

Prohibition was a cultural war that pitted rural Protestant values against urban immigrant traditions.

The movement was defined by an "ethnoreligious" divide. The "Drys"—mostly Methodists, Baptists, and Quakers—viewed alcohol as a sin and a tool of corrupt city politics. Opposing them were the "Wets," primarily Catholics and German Lutherans, who argued that the government had no right to legislate morality. For many immigrants, beer and wine were central to their cultural and social identity, not just a vice.

The political balance finally tipped during World War I. The American beer industry was heavily tied to German-American communities; when the U.S. entered the war against Germany in 1917, the "Wet" opposition was effectively silenced by wartime patriotism. This allowed the 18th Amendment to pass with a staggering supermajority, ratified by 46 out of 48 states.

The Volstead Act created a legal framework riddled with loopholes and unenforceable mandates.

The Volstead Act created a legal framework riddled with loopholes and unenforceable mandates.

While the 18th Amendment banned the "manufacture, sale, or transportation" of intoxicating liquors, it did not actually outlaw the consumption or private possession of alcohol under federal law. The enabling legislation, the Volstead Act, carved out significant exceptions: wine for religious sacraments remained legal, and doctors could prescribe "medicinal" whiskey.

Enforcement was a logistical nightmare. The federal government lacked the personnel and resources to police every basement and back alley in America. In New York City alone, an estimated 30,000 to 100,000 "speakeasy" clubs emerged by 1925. This gap between the law and the public's behavior shifted the alcohol trade from legitimate businesses to violent crime syndicates and black markets.

The "Noble Experiment" produced a statistical paradox of improved public health and soaring violent crime.

The "Noble Experiment" produced a statistical paradox of improved public health and soaring violent crime.

The era’s success is still debated because the data is contradictory. On the medical front, Prohibition worked: rates of liver cirrhosis, alcoholic psychosis, and infant mortality declined significantly. However, because the trade was now controlled by organized crime, the United States saw its highest homicide rates of the early 20th century.

While the "Drys" claimed Prohibition reduced overall consumption, the "Wets" pointed to the "scourge of organized crime" and the loss of personal liberty. By the late 1920s, even former supporters began to turn. The onset of the Great Depression provided the final blow; the government desperately needed the tax revenue that a legal alcohol industry would provide, leading to the ratification of the 21st Amendment in 1933—the only time in U.S. history an amendment was passed solely to repeal another.

Michigan and Detroit policemen inspect the equipment used in a clandestine brewery in a bust.

"Every Day Will Be Sunday When The Town Goes Dry" (1919)

A pro-prohibition political cartoon, from 1874

The Drunkard's Progress – moderate drinking leads to drunkenness and disaster: A lithograph by Nathaniel Currier supporting the temperance movement, 1846

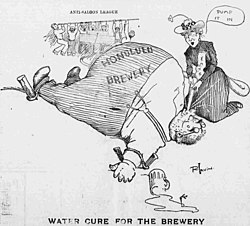

This 1902 illustration from the Hawaiian Gazette newspaper humorously illustrates the Anti-Saloon League and the Woman's Christian Temperance Union's campaign against the producers and sellers of beers in Hawaii. The "water cure" was a torture device.

Governor James P. Goodrich signs the Indiana Prohibition Act, 1917.

A 1915 political cartoon criticizing the alliance between the prohibitionists and women's suffrage movements, showing the Genii of Intolerance, labelled "Prohibition", emerging from its bottle

After the 36th state adopted the amendment on January 16, 1919, the U.S. Secretary of State had to issue a formal proclamation declaring its ratification. Implementing and enforcement bills had to be presented to Congress and state legislatures, to be enacted before the amendment's effective date one year later.

A Budweiser ad from 1919, announcing the reformulation of its flagship beer as required under the Act, ready for sale by 1920

A prescription for medicinal alcohol during prohibition

A policeman with a wrecked automobile and confiscated moonshine, 1922

Disposal of liquor during Prohibition

Orange County, California, sheriff's deputies dumping illegal alcohol, 1932

A Prohibition-era prescription used by U.S. physicians to prescribe liquor as medicine

The Defender Of The 18th Amendment, from Klansmen: Guardians of Liberty published by the Pillar of Fire Church