Printing press

Gutenberg’s genius was not a single invention, but a "modular system" that repurposed agricultural tools for communication.

Gutenberg’s genius was not a single invention, but a "modular system" that repurposed agricultural tools for communication.

While Johannes Gutenberg is often credited with "inventing" printing, his real breakthrough was integrating disparate technologies into a single industrial process. He took the screw-press design used for crushing grapes and olives and adapted it to apply even pressure to a flat bed of type. By combining this with a new alloy of lead, tin, and antimony, he created "movable type" that was durable enough to be reused thousands of times without deforming.

This systems-thinking extended to the ink itself. Traditional water-based inks used in woodblock printing blurred on metal; Gutenberg developed a tackier, oil-based varnish that clung to the type and transferred cleanly to paper. This mechanical synergy turned the slow, artisanal craft of writing into a high-speed manufacturing process.

The press replaced the "bespoke error" of the scribe with the "standardized truth" of mass production.

The press replaced the "bespoke error" of the scribe with the "standardized truth" of mass production.

Before the press, every book was a unique manuscript, hand-copied by a scribe. This was a "lossy" process—errors in one copy were often amplified in the next. The printing press flipped this dynamic. Because every page in a print run was identical, an error could be identified once and corrected for the entire edition. This introduced the concept of the "authoritative text" and standardized languages, spelling, and grammar across entire nations.

The efficiency gains were staggering. A single Renaissance printing press could produce 3,600 pages per workday, whereas a scribe might manage only a few. This collapse in production costs meant that for the first time in human history, a book was no longer a luxury asset owned only by the elite, but a commodity accessible to the emerging middle class.

By breaking the clerical monopoly on Latin, the press became the primary engine of the Protestant Reformation.

By breaking the clerical monopoly on Latin, the press became the primary engine of the Protestant Reformation.

For centuries, the Catholic Church controlled the flow of information because it controlled the scribes and the Latin language. The printing press allowed dissenters like Martin Luther to bypass this hierarchy. Luther famously became the world’s first "best-selling author," printing his German translation of the Bible so that common people could read the text themselves without a priest’s mediation.

This democratization of scripture created a "viral" effect. Luther’s 95 Theses traveled across Germany in two weeks and across Europe in a month. The press didn't just spread new ideas; it created a public sphere where people could debate those ideas simultaneously, laying the groundwork for the modern nation-state and the concept of public opinion.

The transition to steam-powered rotary presses birthed the "Mass Media" and universal literacy.

The transition to steam-powered rotary presses birthed the "Mass Media" and universal literacy.

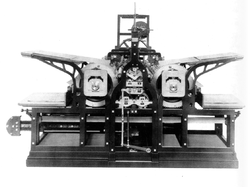

For nearly 400 years, the printing press remained a hand-operated tool. The 19th-century Industrial Revolution fundamentally changed its scale. Friedrich Koenig’s invention of the steam-powered press in 1811 allowed for thousands of sheets to be printed per hour. When the rotary press followed, which printed from continuous rolls of paper rather than individual sheets, the "Penny Press" was born.

This era of industrial printing made newspapers so cheap that they became a daily necessity for the working class. This created a powerful incentive for universal literacy; if you wanted to participate in the economy or politics, you had to be able to read. The press transitioned from a tool for scholars and revolutionaries into the central nervous system of global civilization.

Image from Wikipedia

A medieval university class, 1350s

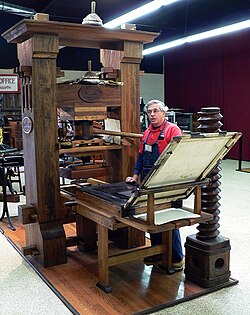

Early modern wine press. Such screw presses, used in Europe for a wide range of uses, provided Gutenberg with the model for his printing press.

Movable type sorted in a letter case and loaded in a composing stick on top

A paper codex of the 42-line Bible, Gutenberg's major work

Printing press, engraving by W Lowry after John Farey Jr., 1819

This woodcut from 1568 shows the left printer removing a page from the press while the one at right inks the text-blocks. Such a duo could reach 14,000 hand movements per working day, printing c. 3,600 pages in the process.

Johannes Gutenberg, 1904 reconstruction

The spread of printing in the 15th century from Mainz, Germany

European book output rose from a few million to around one billion copies within a span of less than four centuries.

"Modern Book Printing" sculpture, commemorating Gutenberg's invention on the occasion of the 2006 World Cup in Germany

Koenig's 1814 steam-powered printing press

Printing press from 1811

Stanhope press from 1842

Imprenta Press V John Sherwin from 1860