Pop art

Pop art shattered the "ivory tower" of fine art by elevating the banality of mass-produced consumer culture.

Pop art shattered the "ivory tower" of fine art by elevating the banality of mass-produced consumer culture.

Before the 1950s, "Fine Art" was expected to be high-minded, unique, and emotionally profound. Pop art aggressively rejected this elitism by pulling its subject matter directly from the supermarket shelf, the comic book, and the television screen. It sought to use images of "low" culture—advertising, labels, and mass media—to challenge the traditional boundaries of what deserves to be in a museum.

By isolating mundane objects like soup cans or soda bottles, Pop artists forced the viewer to consider the aesthetics of their daily environment. The movement didn't just depict popular culture; it celebrated the "disposable" nature of modern life, suggesting that a well-designed advertisement could hold as much visual power as a Renaissance landscape.

While American Pop was a visceral reaction to media saturation, British Pop began as an ironic, academic gaze at American glamour.

While American Pop was a visceral reaction to media saturation, British Pop began as an ironic, academic gaze at American glamour.

Though we often associate Pop art with New York, it actually began in mid-1950s London with "The Independent Group." These British artists viewed American consumerism from a distance, treating it as a fascinating, kitschy "other." For them, Pop was an exercise in semiotics—analyzing how symbols of the "American Dream" functioned as a new kind of visual language.

In contrast, American Pop art was more direct and aggressive. Emerging in the early 1960s, artists like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein weren't just observing the culture; they were living in the belly of the beast. Their work was a reaction against the heavy, psychological intensity of Abstract Expressionism. Where earlier artists sought to express their inner souls through messy paint, American Pop artists preferred the cool, detached look of a factory-made product.

By adopting commercial printing and assembly-line techniques, artists replaced the "artist’s hand" with mechanical objectivity.

By adopting commercial printing and assembly-line techniques, artists replaced the "artist’s hand" with mechanical objectivity.

The most radical shift in Pop art wasn't just what was painted, but how it was made. Artists moved away from the traditional brushstroke—the "signature" of the artist's personality—in favor of techniques used in commercial printing. Roy Lichtenstein famously mimicked "Ben-Day dots," the tiny dots used in cheap comic books, while Andy Warhol utilized photo-silk screening to mass-produce his canvases.

This "mechanical" approach was intentional. It removed the emotional presence of the creator, making the art feel as anonymous and reproducible as the products it depicted. Warhol’s "The Factory" studio wasn't just a clever name; it was a literal rejection of the solitary, tortured artist trope, replacing it with a collaborative, industrial process.

The movement used irony and kitsch to strip everyday objects of their original context and meaning.

The movement used irony and kitsch to strip everyday objects of their original context and meaning.

Pop art is deeply rooted in "found" imagery. It takes a comic strip panel or a celebrity photograph and "decontextualizes" it—removing it from its original purpose and blowing it up to a massive scale. This shift in scale and medium forces a new interpretation. A small comic frame about a crying woman becomes a monumental exploration of melodrama when it's six feet tall on a gallery wall.

This reliance on kitsch—art that is considered to be in poor taste because of excessive garishness or sentimentality—was a deliberate provocation. By presenting "bad" taste as "high" art, Pop artists exposed the arbitrary nature of cultural value. They proved that meaning isn't inherent in an object, but is created by the context in which we view it.

Eduardo Paolozzi, I was a Rich Man's Plaything (1947). Part of his Bunk! series, this is considered the initial bearer of "pop art" and the first to show the word "pop".

Andy Warhol, Campbell's Tomato Juice Box, 1964. Synthetic polymer paint and silkscreen ink on wood, 10 inches × 19 inches × 9½ inches (25.4 × 48.3 × 24.1 cm), Museum of Modern Art, New York City

Charles Demuth, I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold 1928, collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City

Richard Hamilton's collage Just what is it that makes today's homes so different, so appealing? (1956) is one of the earliest works to be considered "pop art".

The Cheddar Cheese canvas from Andy Warhol's Campbell's Soup Cans, 1962.

Michel Tuffery's Pisupo lua afe (Corned beef 2000) (1994)

The Olivetti Valentine designed by Ettore Sottsass with Perry A. King and Albert Leclerc

Paul Van Hoeydonck's Fallen Astronaut

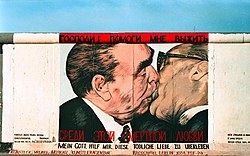

Dmitri Vrubel's painting My God, Help Me to Survive This Deadly Love (1990)