Plato

Plato abandoned an aristocratic career in poetry and politics to seek stability in an Athens ravaged by war and corruption.

Plato abandoned an aristocratic career in poetry and politics to seek stability in an Athens ravaged by war and corruption.

Born into an influential Athenian family during the Peloponnesian War, Plato’s early life was defined by chaos. He was a descendant of Solon, the founder of Athenian democracy, and was expected to enter public life. However, his disillusionment began early: he watched his relatives join the "Thirty Tyrants"—a brutal puppet government installed by Sparta—and eventually witnessed the restored democracy execute his mentor, Socrates.

Legend suggests Plato was originally a poet and a wrestler (the name "Plato" may be a nickname meaning "broad-shouldered"). Following the death of Socrates, he reportedly burned his tragedies and turned entirely to philosophy. This shift wasn't just a personal choice; it was a response to a world that seemed incapable of justice. He spent the rest of his life trying to find a form of government and knowledge that was not subject to the whims of the mob or the cruelty of tyrants.

He argued that the physical world is merely a flawed "copy" of a perfect, mathematical reality known as the Forms.

He argued that the physical world is merely a flawed "copy" of a perfect, mathematical reality known as the Forms.

Plato’s most famous contribution is the Theory of Forms, his solution to the tension between change and permanence. Borrowing from Heraclitus (who argued everything is in flux) and Parmenides (who argued change is an illusion), Plato proposed two worlds. The "apparent" world we see is a shifting, decaying imitation. The "real" world consists of Forms—eternal, unchanging archetypes of things like Beauty, Justice, and even "Tableness."

For Plato, mathematics was the bridge to this higher reality. While a physical circle drawn in the sand is always imperfect, the mathematical concept of a circle is perfect and eternal. He believed that the goal of the philosopher is to look past the "shadows" of the material world and use reason to grasp these ultimate truths. This perspective laid the groundwork for Western science and theology, influencing everything from early Christian thought to modern theoretical physics.

By hiding his own voice behind the character of Socrates, Plato created a literary tradition that blurs the line between teacher and student.

By hiding his own voice behind the character of Socrates, Plato created a literary tradition that blurs the line between teacher and student.

Unlike almost any other philosopher, Plato never speaks in his own voice in his writings. Instead, he wrote "dialogues"—philosophical plays where his teacher, Socrates, debates various Athenians. This creates the "Socratic Problem": it is nearly impossible to tell where the historical Socrates ends and Plato’s own ideas begin. While the early dialogues likely reflect the real Socrates' method of questioning, the later works use "Socrates" as a mouthpiece for Plato’s complex metaphysical theories.

This literary choice was revolutionary. By using the Socratic method—a relentless series of questions designed to expose contradictions—Plato forced his readers to think for themselves rather than just absorbing a lecture. While his student Aristotle would later write systematic textbooks, Plato’s works remain open-ended and ironic, mimicking the lived experience of a conversation.

He viewed the human soul as a three-way struggle between reason, spirit, and physical appetite.

He viewed the human soul as a three-way struggle between reason, spirit, and physical appetite.

Plato was one of the first to propose a structured psychology. He argued the soul is immortal and divided into three parts: Reason (the head), Spirit (the chest), and Appetite (the belly). In his view, a "just" person is someone whose Reason controls their Appetites with the help of their Spirit. He even extended this to his vision of the ideal state, where "Philosopher Kings" represent reason, soldiers represent spirit, and the working class represents appetite.

Crucially, Plato believed that "learning" is actually a process of "recollection." He argued that because the soul is immortal, it has already seen the perfect Forms before being born into a physical body. When we learn a difficult truth—like a geometric proof—we aren't discovering something new; we are remembering a truth our soul already knew but forgot at birth.

The Academy was established to turn real-world tyrants into "Philosopher-Kings," though the experiment often failed.

The Academy was established to turn real-world tyrants into "Philosopher-Kings," though the experiment often failed.

In 383 BC, Plato founded the Academy, often cited as the first university in the Western world. It wasn't just a place for abstract thought; it was a training ground for political advisors. Plato’s greatest ambition was to realize his "Philosopher-King" ideal in the real world. He traveled to Syracuse three times to tutor Dionysius II, the young ruler of the city, hoping to turn the tyrant into a wise constitutional monarch.

The Syracuse experiments were a disaster. Plato was nearly sold into slavery during his first trip and was held against his will during his third. Despite these practical failures, the Academy survived for centuries, producing thinkers like Aristotle and ensuring that Plato’s complete works survived for over 2,400 years. As mathematician Alfred North Whitehead famously put it, the entire European philosophical tradition is essentially "a series of footnotes to Plato."

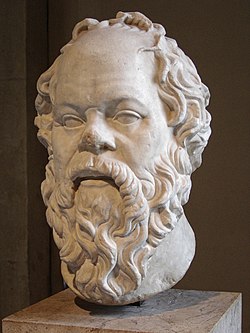

Image from Wikipedia

Plato was one of the devoted young followers of Socrates, whose bust is pictured above.

Heraclitus (1628) by Hendrick ter Brugghen. Heraclitus saw a world in flux, with everything always in conflict, constantly changing.

The mathematical and mystical teachings of the followers of Pythagoras, pictured above, exerted a strong influence on Plato.

Plato's Academy mosaic in the villa of T. Siminius Stephanus in Pompeii, around 100 BC to 100 CE

"What is justice?" forms one of the core quandaries of the Republic.

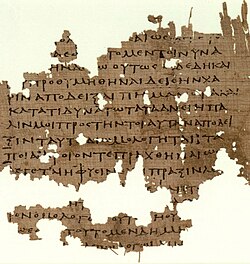

Papyrus from Oxyrhynchus, with fragment of Plato's Republic

Painting of a scene from Plato's Symposium (Anselm Feuerbach, 1873)

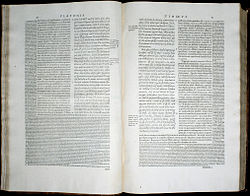

Volume 3, pp. 32–33, of the 1578 Stephanus edition of Plato, showing a passage of Timaeus with the Latin translation and notes of Jean de Serres

The School of Athens fresco features Plato (left), holding his Timaeus while he gestures to the heavens. Aristotle (right) gestures to the earth while holding a copy of Nicomachean Ethics.