Plate tectonics

Earth’s outer shell is a broken mosaic of rigid plates floating on a hot, slow-moving interior.

Earth’s outer shell is a broken mosaic of rigid plates floating on a hot, slow-moving interior.

The Earth is not a solid ball of rock; instead, its outer layer—the lithosphere—is fractured into about 15 to 20 major "tectonic plates." These plates vary in thickness, with dense oceanic crust sitting lower than the lighter, thicker continental crust. Beneath them lies the asthenosphere, a layer of the mantle that is solid but "ductile," meaning it flows like extremely thick taffy under immense pressure and heat.

This mechanical distinction is what allows for movement. Because the lithosphere is cooler and more rigid than the hot mantle below, it can slide across the top of the asthenosphere. The plates aren't just the continents we see on a map; they are massive slabs of rock that carry both entire oceans and continents on their backs, moving at about the same speed your fingernails grow.

The planet functions as a massive heat engine, recycling its own surface to regulate its temperature.

The planet functions as a massive heat engine, recycling its own surface to regulate its temperature.

The movement of plates is driven by the Earth’s internal heat, primarily left over from its formation and the decay of radioactive elements. This heat creates convection currents in the mantle, but the real "engine" of plate movement is gravity. In a process called "slab pull," the cold, dense edges of old oceanic plates sink into the mantle at subduction zones, dragging the rest of the plate behind them.

This creates a continuous recycling system. New crust is "born" at mid-ocean ridges where magma rises to fill gaps, and old crust is "destroyed" as it sinks back into the depths to be remelted. Without this process, the Earth would likely be a geologically dead world like Mars, unable to regulate its climate or replenish the minerals necessary for life.

Geography is forged at the volatile borders where plates collide, grind, or pull apart.

Geography is forged at the volatile borders where plates collide, grind, or pull apart.

The most dramatic features of our planet—mountains, deep-sea trenches, and volcanoes—are not random; they are the direct result of plate interactions. At "divergent" boundaries, plates pull apart to create new seafloor or rift valleys. At "transform" boundaries, like the San Andreas Fault, they slide past each other, storing massive amounts of elastic energy that is eventually released as violent earthquakes.

The most transformative interactions occur at "convergent" boundaries. When two continental plates collide, neither wants to sink, so the crust crumples upward to form massive mountain ranges like the Himalayas. When an oceanic plate hits a continental plate, it dives underneath, creating "subduction zones" that generate the world’s deepest trenches and most explosive volcanic arcs, such as the Ring of Fire.

A ridiculed theory of "drifting continents" became the unifying framework of modern geology in just one decade.

A ridiculed theory of "drifting continents" became the unifying framework of modern geology in just one decade.

For centuries, mapmakers noticed that South America and Africa looked like matching puzzle pieces, but the scientific community lacked a mechanism to explain why. In 1912, Alfred Wegener proposed "Continental Drift," but he was largely dismissed because he couldn't explain how solid rock could plow through the ocean floor.

The breakthrough came in the 1950s and 60s through seafloor mapping and the discovery of "paleomagnetism"—magnetic patterns in rocks that proved the seafloor was spreading from the center outward. This evidence turned a fringe idea into a scientific revolution. By the late 1960s, plate tectonics became the "unifying theory" of geology, providing a single explanation for everything from the distribution of fossils to the location of gold deposits.

Tectonics serves as Earth's long-term thermostat, making the planet uniquely habitable.

Tectonics serves as Earth's long-term thermostat, making the planet uniquely habitable.

Beyond shaping the landscape, plate tectonics plays a critical role in the carbon cycle. When plates subduct, they carry carbon-rich sediments into the Earth's interior. This carbon is later released back into the atmosphere as CO2 through volcanic eruptions. This feedback loop helps maintain a stable global temperature over millions of years.

If the Earth’s "conveyor belt" stopped, the planet’s atmosphere would lose its ability to recycle carbon, likely leading to a runaway greenhouse effect or a permanent deep-freeze. Plate tectonics isn't just a geological process; it is a fundamental requirement for the long-term survival of a complex biosphere.

Map of Earth's 16 principal tectonic plates Convergent: Collision zone Subduction zone Divergent: Extension zone Spreading centre Transform: Dextral transform Sinistral transform

Divergent boundary

Convergent boundary

Transform boundary

Plate motion based on Global Positioning System (GPS) satellite data from NASA JPL. Each red dot is a measuring point and vectors show direction and magnitude of motion.

Detailed map showing the tectonic plates with their movement vectors

Alfred Wegener in Greenland in the winter of 1912–13

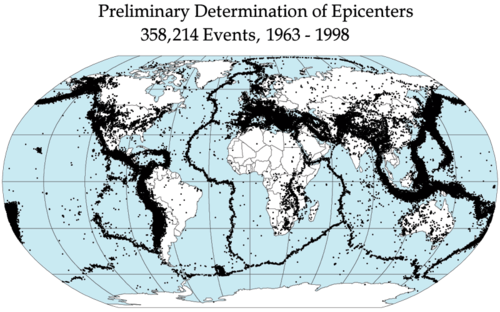

Global earthquake epicenters, 1963–1998. Most earthquakes occur in narrow belts that correspond to the locations of lithospheric plate boundaries.

Map of earthquakes in 2016

Seafloor magnetic striping