Parasitism

Parasitism is life’s most successful "lifestyle," accounting for nearly half of all known species.

Parasitism is life’s most successful "lifestyle," accounting for nearly half of all known species.

Far from being a biological anomaly, parasitism is a dominant ecological strategy that has evolved independently dozens of times across the tree of life. From microscopic protozoa to complex plants and insects, the fundamental "shortcut" of stealing resources from another organism is so effective that it arguably outcompetes independent living in many environments.

This ubiquity means that almost every free-living organism—including humans—serves as a host to multiple parasite species. It is a fundamental driver of biodiversity; because parasites are often highly specialized to a single host species, the more hosts that exist, the more parasites evolve to fill those specific niches.

The "Red Queen" dynamic creates a never-ending genetic arms race between host and intruder.

The "Red Queen" dynamic creates a never-ending genetic arms race between host and intruder.

In evolutionary biology, the Red Queen hypothesis suggests that organisms must constantly adapt and evolve just to maintain their current survival status. Parasites exert massive selective pressure: a host that cannot defend itself dies or fails to reproduce, while a parasite that cannot bypass host defenses starves.

This leads to a sophisticated back-and-forth. Hosts develop complex immune systems and defensive behaviors, while parasites evolve molecular "cloaking devices," biochemical overrides, or the ability to manipulate the host's DNA. This conflict is responsible for much of the genetic diversity seen in nature, as sexual reproduction itself may have evolved primarily as a way for hosts to "shuffle the deck" and stay one step ahead of specialized parasites.

Parasites are classified by their "proximity to the host," ranging from external hitchhikers to internal body-snatchers.

Parasites are classified by their "proximity to the host," ranging from external hitchhikers to internal body-snatchers.

Biologists categorize parasites based on where they live and how they consume. Ectoparasites, like ticks and lice, live on the surface, while endoparasites, like tapeworms, inhabit the internal organs or bloodstream. Each requires a different toolkit: ectoparasites need specialized "gripping" appendages, while endoparasites often lose their digestive systems entirely, absorbing pre-digested nutrients directly through their skin.

The most extreme form is the "parasitoid." Unlike true parasites, which generally benefit from keeping their host alive, parasitoids (mostly wasps and flies) eventually kill their host. They often consume the host’s non-essential tissues first to keep it alive as long as possible before finally emerging from the carcass—a strategy that bridges the gap between parasitism and predation.

Beyond physical nutrients, social and brood parasites hijack the labor and instincts of other species.

Beyond physical nutrients, social and brood parasites hijack the labor and instincts of other species.

Parasitism isn't always about eating flesh; it can also be about stealing effort. Brood parasites, most famously the cuckoo bird, lay their eggs in the nests of other species. The "host" parents then spend their energy raising a chick that may even push the host's own offspring out of the nest.

Social parasites take this further, infiltrating the complex societies of ants or bees. Some "slave-making" ants raid the nests of other species, stealing pupae to be raised as workers in their own colony. These parasites have abandoned the ability to care for their own young or even feed themselves, relying entirely on the hijacked labor of their "slaves."

Parasites act as the hidden "dark matter" of ecosystems, regulating populations and biomass.

Parasites act as the hidden "dark matter" of ecosystems, regulating populations and biomass.

While often overlooked in food web models, parasites can actually outweigh top predators in terms of total biomass in an ecosystem. They function as invisible regulators, preventing any one species from becoming too dominant. When a host population grows too large, parasites spread more easily, naturally thinning the population and maintaining ecological balance.

They also drive "trophic transmission," frequently altering the behavior of their hosts to make them more likely to be eaten by the parasite's next target. For example, some parasites make fish swim closer to the surface or mice lose their fear of cats. In this way, parasites act as puppet masters, directing the flow of energy and nutrients through the entire environment.

A fish parasite, the isopod Cymothoa exigua, replacing the tongue of a Lithognathus

Head (scolex) of tapeworm Taenia solium, an intestinal parasite, has hooks and suckers to attach to its host

The parasitic castrator Sacculina carcini (highlighted) attached to its crab host

Human head-lice are directly transmitted obligate ectoparasites

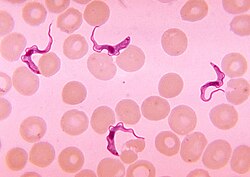

The vector-transmitted protozoan endoparasite Trypanosoma among human red blood cells

Idiobiont parasitoid wasps immediately paralyse their hosts for their larvae (Pimplinae, pictured) to eat.

Koinobiont parasitoid wasps like this braconid lay their eggs via an ovipositor inside their hosts, which continue to grow and moult.

Phorid fly (centre left) is laying eggs in the abdomen of a worker honey-bee, altering its behaviour.

Mosquitoes are micropredators and important vectors of disease

Life cycle of Entamoeba histolytica, an anaerobic parasitic protozoan transmitted by the fecal–oral route

The large blue butterfly is an ant mimic and social parasite.

In brood parasitism, the host raises the young of another species: here a cowbird's egg in an Eastern phoebe's nest.

The great skua is a powerful kleptoparasite, relentlessly pursuing other seabirds until they disgorge their catches of food.

Encarsia perplexa (centre), a parasitoid of citrus blackfly (lower left), is also an adelphoparasite, laying eggs in larvae of its own species

Cuscuta (a dodder), a stem holoparasite, on an acacia tree