Panama Canal

An 82-kilometer liquid elevator uses gravity and 200 million liters of fresh water to lift ships over a continental divide.

An 82-kilometer liquid elevator uses gravity and 200 million liters of fresh water to lift ships over a continental divide.

The Panama Canal is not a simple trench; it is a complex hydraulic machine. Because the Isthmus of Panama is mountainous, engineers could not easily dig down to sea level. Instead, they dammed the Chagres River to create Gatun Lake—an artificial reservoir 26 meters (85 feet) above sea level. Ships enter a series of concrete locks that act as massive water elevators, lifting vessels up to the lake's level for the transit across the continent and then lowering them back down on the other side.

This engineering shortcut relies entirely on fresh water. Each single ship transit flushes approximately 200 million liters (52 million gallons) of water out to sea. Because the system depends on rainfall to replenish Gatun Lake, the canal’s capacity is ironically tethered to the local ecosystem; during severe droughts, water levels drop, forcing the Panama Canal Authority to restrict the depth and number of ships that can pass through.

The first attempt to conquer the isthmus collapsed under the weight of 22,000 deaths and an obsession with sea-level transit.

The first attempt to conquer the isthmus collapsed under the weight of 22,000 deaths and an obsession with sea-level transit.

In 1881, Ferdinand de Lesseps—the Frenchman behind the Suez Canal—attempted to replicate his Egyptian success in the Central American jungle. However, Suez was a flat desert, while Panama was a vertical jungle of volcanic rock and torrential rain. De Lesseps insisted on a sea-level canal without locks, an engineering miscalculation that led to endless landslides at the Culebra Cut.

The project became a humanitarian disaster. Unaware that mosquitoes carried yellow fever and malaria, the French workforce was decimated; at one point, the death rate exceeded 200 workers per month. By 1889, the company went bankrupt, having squandered $287 million and the lives of an estimated 22,000 men. The ensuing "Panama affair" scandal in France was so severe it led to the prosecution of iconic figures like Gustave Eiffel.

A $40 million "fire sale" and aggressive lobbying shifted the American focus from Nicaragua to Panama.

A $40 million "fire sale" and aggressive lobbying shifted the American focus from Nicaragua to Panama.

At the turn of the 20th century, the United States originally favored building a canal through Nicaragua, which was considered technically easier. The Panama route only became the American choice through the relentless lobbying of William Nelson Cromwell and Philippe Bunau-Varilla. Bunau-Varilla, representing the failed French company's assets, slashed his asking price from $109 million to $40 million to entice President Theodore Roosevelt.

Roosevelt’s intervention was decisive. After personal meetings with engineers and commissioners, he pushed for the Panama route, leading to the Spooner Act of 1902. When the Colombian government (which then controlled Panama) hesitated to sign the treaty, the U.S. supported Panamanian separatists, eventually gaining control of the "Canal Zone." The U.S. succeeded where the French failed by prioritizing mosquito control and pivoting to a lock-based design.

The 2016 expansion was a $5 billion survival move to accommodate the "Neopanamax" era of global shipping.

The 2016 expansion was a $5 billion survival move to accommodate the "Neopanamax" era of global shipping.

For a century, the size of the world’s cargo ships was dictated by the dimensions of the canal’s original locks, a standard known as "Panamax." However, as global trade evolved, ships became too large for the 33.5-meter-wide chambers. To avoid becoming obsolete, Panama launched a massive expansion project between 2007 and 2016, adding a third lane of much wider and deeper locks.

This expansion allows for "Neopanamax" vessels, which can carry more than double the cargo of previous ships. The canal now handles over 14,000 vessels annually, acting as the primary artery for trade between the U.S. East Coast and Asia. Despite the 1999 handover of the canal from American to Panamanian control, the U.S. remains its top user, followed closely by China and North Asian trade partners.

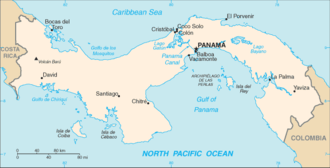

Image from Wikipedia

Location of Panama between the Pacific Ocean (bottom) and the Caribbean Sea (top), with the canal at top center

An 1885 map showing the Railway and the proposed Panama Canal route

Ferdinand de Lesseps, the French originator of the Suez Canal and the Panama Canal

Part de Fondateur of the Compagnie Universelle du Canal Interocéanique de Panama, issued 29 November 1880

United States President Theodore Roosevelt (1901–1909), the driving force behind US construction of the Panama Canal.

The US's intentions to influence the area (especially the Panama Canal construction and control) led to the separation of Panama from Colombia in 1903.

1903 cartoon: "Go Away, Little Man, and Don't Bother Me". President Theodore Roosevelt intimidating Colombia to acquire the Panama Canal Zone.

President Theodore Roosevelt sitting on a Bucyrus steam shovel at Culebra Cut, 1906

Construction work on the Gaillard Cut, 1907

Construction of locks on the Panama Canal, 1913

A Marion steam shovel excavating the Panama Canal, 1908

The Panama Canal locks under construction, 1910

The first ship to transit the canal at the formal opening, SS Ancon, passes through on 15 August 1914.

Spanish laborers working on the Panama Canal in the early 1900s