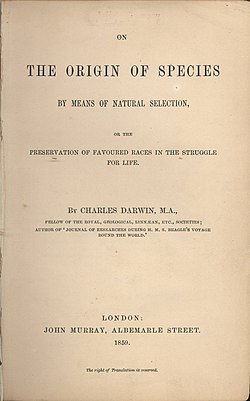

On the Origin of Species

Evolution operates through a mechanical "struggle for existence" where small heritable advantages drive the origin of new species.

Evolution operates through a mechanical "struggle for existence" where small heritable advantages drive the origin of new species.

Darwin’s theory is built on a brutal but simple logic of elimination. He observed that while species are fertile enough to overpopulate, resources remain limited. This creates an inevitable struggle for survival. Because individuals within a population vary, those with traits better suited to their environment are more likely to survive and reproduce. Over generations, these "favoured" traits accumulate, eventually causing populations to diverge into entirely new species.

This process, known as natural selection, replaced the idea of "progressive" evolution. Unlike his predecessors, Darwin argued that evolution has no predetermined goal or inherent drive toward complexity. Instead, it is a branching process of common descent—a genealogical tree where every living thing is related through a long chain of ancestors.

Darwin overturned a centuries-old worldview that saw species as fixed, divinely designed entities within a static hierarchy.

Darwin overturned a centuries-old worldview that saw species as fixed, divinely designed entities within a static hierarchy.

Before 1859, the English scientific establishment was deeply intertwined with the Church of England. Science was practiced as "natural theology," where the complexity of a beetle or a bird was seen as direct evidence of a benevolent Creator’s handiwork. In this view, species were "fixed"—they did not change, and they did not go extinct except by divine catastrophe.

The idea of "transmutation" (evolution) was considered socially and politically dangerous. It suggested that humans were not unique creations but merely another branch of the animal kingdom. By providing a mountain of evidence for common descent, Darwin shifted science away from supernatural explanations and toward "scientific naturalism," where the history of life could be explained by observable, physical laws.

A twenty-year delay in publication allowed Darwin to move from speculative intuition to a "mass of evidence" built on barnacles and pigeon breeding.

A twenty-year delay in publication allowed Darwin to move from speculative intuition to a "mass of evidence" built on barnacles and pigeon breeding.

Darwin conceived his theory in 1838 after reading Thomas Malthus, but he didn't publish Origin until 1859. This delay was not mere procrastination; it was a strategic gathering of "ammunition." He spent eight years becoming the world's leading expert on barnacles to establish his scientific credentials and conducted exhaustive experiments on how seeds survive salt water and how pigeon breeders select for specific traits.

He was also wary of the backlash. A popular but scientifically flawed book called Vestiges had recently been savaged by the clergy and the scientific elite for its amateurish take on evolution. Darwin knew that to succeed, his book needed to be a "long argument" that addressed every possible objection—from the lack of transitional fossils to the evolution of complex organs like the eye—before his critics could even raise them.

The book sparked a "secularization" of science that eventually unified all life sciences under a single, branching tree.

The book sparked a "secularization" of science that eventually unified all life sciences under a single, branching tree.

Upon publication, Origin was an immediate sensation, written for non-specialists and scientists alike. While it took another two decades for the scientific community to agree that evolution had occurred, they were initially skeptical of natural selection as the primary driver. This period, known as "the eclipse of Darwinism," saw various alternative theories compete for dominance.

It wasn't until the "modern synthesis" of the 1930s and 40s—which combined Darwin’s selection with the new science of genetics—that his theory became the undisputed foundation of biology. Today, Darwin’s concept of evolutionary adaptation is the unifying principle of the life sciences, providing the framework for everything from medicine and ecology to the study of the human genome.

Image from Wikipedia

Darwin pictured shortly before publication

Cuvier's 1799 paper on living and fossil elephants helped establish the reality of extinction.

In mid-July 1837 Darwin started his "B" notebook on Transmutation of Species, and on page 36 wrote "I think" above his first evolutionary tree.

Darwin researched how the skulls of different pigeon breeds varied, as shown in his Variation of Plants and Animals Under Domestication of 1868.

A photograph of Alfred Russel Wallace (1823–1913) taken in Singapore in 1862

On the Origin of Species by means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, 2nd edition. By Charles Darwin, John Murray, London, 1860. National Museum of Scotland.

American botanist Asa Gray (1810–1888)

John Gould's illustration of Darwin's rhea was published in 1841. The existence of two rhea species with overlapping ranges influenced Darwin.

This tree diagram, used to show the divergence of species, is the only illustration in the Origin of Species.

In the 1870s, British caricatures of Darwin with a non-human ape body contributed to the identification of evolutionism with Darwinism.

Huxley used illustrations to show that humans and apes had the same basic skeletal structure.

Haeckel showed a main trunk leading to mankind with minor branches to various animals, unlike Darwin's branching evolutionary tree.

The liberal theologian Baden Powell defended evolutionary ideas by arguing that the introduction of new species should be considered a natural rather than a miraculous process.

A modern phylogenetic tree based on genome analysis shows the three-domain system.