Olive oil

More than a condiment, olive oil is the liquid foundation of Mediterranean civilization and its ancient "triad" of survival.

More than a condiment, olive oil is the liquid foundation of Mediterranean civilization and its ancient "triad" of survival.

Olive oil sits alongside wheat and grapes as one of the three core food plants of Mediterranean cuisine. While it’s now a global pantry staple, its cultivation dates back to the 8th millennium BC in Asia Minor. It wasn't just food; it was a primary source of wealth and economic power for the Minoans and Greeks.

By the time of the Roman Empire, olive production had expanded into a massive industrial network. The Romans perfected the trapetum (olive mill) and developed sophisticated trade routes, ensuring that high-quality oil from regions like Italy and Spain was accessible across the empire. Today, Spain remains the dominant force, producing roughly 24% of the world's supply.

Extraction is a race against oxidation, moving from ancient stone mills to high-speed modern centrifuges.

Extraction is a race against oxidation, moving from ancient stone mills to high-speed modern centrifuges.

The goal of production is to separate oil from the fruit's water and solids without damaging its chemistry. Traditional methods used large millstones to create a paste, which was then squeezed through woven mats. Modern methods have replaced these with "malaxation" (slow stirring to aggregate oil droplets) and high-speed centrifuges that separate the oil in seconds.

The "Extra Virgin" (EVOO) label isn't just marketing—it’s a chemical and sensory grade. To qualify, the oil must be extracted solely by mechanical means (no heat or chemicals) and maintain a free acidity level below 0.8%. This purity preserves the high concentration of oleic acid and antioxidants that provide both its health benefits and its distinct, often peppery, flavor profile.

Culinary science debunks the myth that olive oil is unsuitable for high-heat cooking and frying.

Culinary science debunks the myth that olive oil is unsuitable for high-heat cooking and frying.

A common misconception suggests that olive oil has a dangerously low smoke point. In reality, refined olive oils can handle temperatures up to 230 °C (446 °F), making them perfectly safe for deep frying. Even high-quality Extra Virgin oil, with a smoke point between 180–215 °C (356–419 °F), is stable enough for most domestic sautéing and pan-frying.

The primary "risk" of heating premium EVOO isn't safety, but flavor. High temperatures burn off the volatile compounds that give the oil its nuanced taste. This is why chefs typically use refined oils for frying and save the expensive, unrefined "virgin" oils for finishing dishes, salad dressings, or dipping bread.

Beyond the kitchen, olive oil serves as a sacred medium for light, healing, and divine authority.

Beyond the kitchen, olive oil serves as a sacred medium for light, healing, and divine authority.

Olive oil is deeply embedded in the "Big Three" Abrahamic religions. In Judaism, it was the only fuel permitted for the Menorah in the Temple of Jerusalem, symbolizing purity. In Christianity, "Sacred Chrism"—a mixture of olive oil and balsam—is used by bishops for baptisms, confirmations, and the anointing of monarchs during coronations.

This symbolic weight carries into secular history as well. The olive branch has served as a universal symbol of peace for millennia, stemming from Greek mythology. In the contest for the patronage of Athens, the goddess Athena won over the citizens by gifting them an olive tree—a source of food, light, and medicine—which was judged more valuable than Poseidon’s gift of a salt spring.

Image from Wikipedia

Ancient Greek olive oil production workshop in Klazomenai, Ionia (modern Turkey)

Ancient oil press (Bodrum Museum of Underwater Archaeology, Bodrum, Turkey)

Olive crusher (trapetum) in Pompeii (79 AD)

The Manufacture of Oil, 16th-century engraving by Jost Amman

Vinegar and olive oil

Olive oil served with bread

A cold press olive oil machine in Israel

Olive oil mill

A bottle of Italian olive oil

Italian label for "extra vergine" olive oil

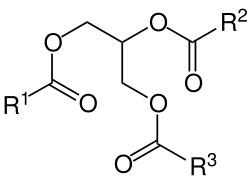

General chemical structure of food fats (triglyceride). R1, R2, and R3 are alkyl groups (approx. 20%) or alkenyl groups (approx. 80%).

Egyptian olives