Nuclear fusion

Fusion generates energy by crushing light atoms together until the "strong force" overcomes electrical repulsion.

Fusion generates energy by crushing light atoms together until the "strong force" overcomes electrical repulsion.

Every atom's nucleus is positively charged, meaning they naturally repel one another like the matching poles of magnets. To trigger fusion, these nuclei must be forced so close together that the "strong nuclear force"—which only acts over microscopic distances—can take over and glue them into a single, heavier nucleus. This process releases a staggering amount of energy because the resulting nucleus weighs slightly less than the sum of its parts; that "missing" mass is converted directly into energy according to Einstein’s $E=mc^2$.

In nature, this happens in the cores of stars, where the sheer weight of gravity provides the necessary pressure. On Earth, we lack that gravitational mass, so we must compensate by heating hydrogen isotopes to temperatures exceeding 100 million degrees Celsius—far hotter than the center of the sun. At these temperatures, matter becomes plasma, a chaotic soup of electrons and nuclei that is notoriously difficult to handle.

Humanity is attempting to "bottle the sun" using either massive magnetic cages or high-powered laser strikes.

Humanity is attempting to "bottle the sun" using either massive magnetic cages or high-powered laser strikes.

Engineers primarily use two methods to contain the 100-million-degree plasma required for fusion. The first, Magnetic Confinement, uses a donut-shaped machine called a Tokamak. Powerful superconducting magnets suspend the plasma in mid-air, preventing it from touching and melting the reactor walls. The goal is to keep the plasma stable long enough for the nuclei to collide and fuse continuously.

The second method, Inertial Confinement, takes a "micro-explosion" approach. Researchers use some of the world's most powerful lasers to blast a tiny fuel pellet for a fraction of a second. This causes the pellet to implode with such intensity that it reaches the density and temperature required for fusion. While magnetic fusion aims for a steady burn, inertial fusion is more like an internal combustion engine, relying on rapid, discrete pulses of energy.

The ideal fuel source is abundant in seawater but requires a rare radioactive partner to ignite efficiently.

The ideal fuel source is abundant in seawater but requires a rare radioactive partner to ignite efficiently.

The most "attainable" fusion reaction on Earth uses two isotopes of hydrogen: deuterium and tritium. Deuterium is plentiful and easily extracted from ordinary seawater, making it an almost inexhaustible resource. However, tritium is radioactive and extremely rare in nature. To make fusion commercially viable, reactors must "breed" their own tritium by lining the reactor walls with lithium, which transforms into tritium when struck by neutrons from the fusion reaction.

The ultimate goal is "Aneutronic fusion," using fuels like Boron-11. These reactions produce no neutrons, meaning the reactor wouldn't become radioactive over time and energy could be captured directly as electricity without needing to boil water to turn a turbine. However, these reactions require temperatures ten times higher than the deuterium-tritium mix, keeping them firmly in the realm of future tech.

Fusion is a "fail-safe" power source that produces zero carbon and no long-lived high-level radioactive waste.

Fusion is a "fail-safe" power source that produces zero carbon and no long-lived high-level radioactive waste.

Unlike nuclear fission—which splits heavy atoms like Uranium—fusion cannot trigger a chain reaction or a "meltdown." If a fusion reactor is damaged or the plasma is disturbed, the reaction simply cools and stops within seconds. There is no risk of a runaway explosion. Furthermore, the primary byproduct of the reaction is helium, an inert gas that poses no environmental threat and is actually a valuable industrial resource.

While the reactor components themselves become radioactive over their 30-year lifespan due to neutron bombardment, this waste is much "cleaner" than fission waste. It loses most of its radioactivity within 50 to 100 years, rather than the thousands of years required for spent nuclear fuel. This makes fusion the "Holy Grail" of energy: high-density, carbon-free, and inherently safe.

Fusion plasma in China's Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak.

M. Stanley Livingston and Ernest Lawrence in front of UCRL's 27-inch cyclotron in 1934. These devices were used for many early experiments demonstrating deuterium fusion.

The US has been counting on private industry to lead in fusion power, while more recently China's government has made fusion a national priority. In 2025, $2.1 billion was poured into a single Chinese state-owned fusion company, an amount two and a half times the U.S. Energy Department's annual fusion budget.

Fusion of deuterium with tritium creating helium-4, freeing a neutron, and releasing 17.59 MeV as kinetic energy of the products while a corresponding amount of mass disappears, in agreement with kinetic E = ∆mc2, where Δm is the decrease in the total rest mass of particles

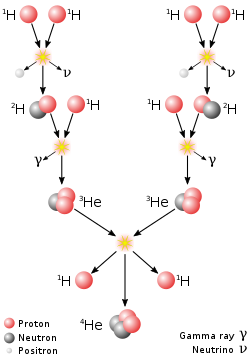

The proton–proton chain reaction, branch I, dominates in stars the size of the Sun or smaller.

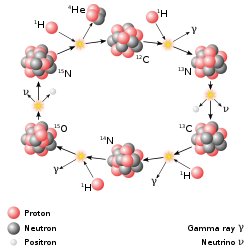

The CNO cycle dominates in stars heavier than the Sun.

The nuclear binding energy curve. The formation of nuclei with masses up to iron-56 releases energy, as illustrated above.

The electrostatic force between the positively charged nuclei is repulsive, but when the separation is small enough, the quantum effect will tunnel through the wall. Therefore, the prerequisite for fusion is that the two nuclei be brought close enough together for a long enough time for quantum tunneling to act.

The fusion reaction rate increases rapidly with temperature until it maximizes and then gradually drops off. The DT rate peaks at a lower temperature (about 70 keV, or 800 million kelvin) and at a higher value than other reactions commonly considered for fusion energy.

The Tokamak à configuration variable, research fusion reactor, at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (Switzerland)