Natural selection

Natural selection is an unconscious filter that transforms random mutations into non-random biological design.

Natural selection is an unconscious filter that transforms random mutations into non-random biological design.

Contrary to popular belief, evolution isn't entirely "random." While the mutations that create variation occur by chance, natural selection is the deterministic force that decides which traits survive. It acts as a sieve: harmful variations are discarded, while beneficial ones are preserved because the individuals carrying them are more likely to reach reproductive age.

This process explains how complex, functional structures—like the human eye or a bird’s wing—can emerge without a conscious designer. It is a feedback loop where the environment "vets" every generation, ensuring that only the blueprints capable of flourishing in a specific niche are passed down to the next.

Evolution requires a "perfect storm" of variation, inheritance, and a struggle for limited resources.

Evolution requires a "perfect storm" of variation, inheritance, and a struggle for limited resources.

The engine of selection cannot run without three specific conditions. First, there must be variation; if every individual in a population were identical, there would be nothing to "select." Second, those differences must be heritable, passed from parent to offspring through genetic material.

The final catalyst is the "struggle for existence." Populations naturally produce more offspring than their environment can support. This creates a competitive pressure where even a tiny advantage—a slightly sharper beak or better camouflage—becomes the difference between a genetic dead-end and a lineage that continues for millennia.

Biological fitness is measured by reproductive legacy rather than physical strength or longevity.

Biological fitness is measured by reproductive legacy rather than physical strength or longevity.

In common parlance, "survival of the fittest" suggests that the biggest or strongest wins. In biology, however, fitness is a strictly mathematical term referring to an organism's ability to pass its genes to the next generation. A powerful lion that lives 20 years but produces no cubs has a fitness of zero.

This explains why some organisms evolve traits that actually hinder their individual survival. The extravagant tail of a peacock makes it an easy target for predators, but because it attracts more mates, it increases "reproductive success." Natural selection prioritizes the persistence of the gene over the comfort or safety of the individual.

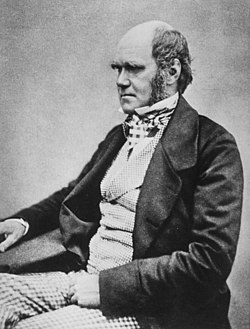

Darwin and Wallace replaced a static view of life with the mathematical inevitability of change.

Darwin and Wallace replaced a static view of life with the mathematical inevitability of change.

Before the mid-19th century, species were largely seen as fixed entities. In 1858, Charles Darwin and Alfred Russel Wallace independently proposed that species are actually fluid populations in a constant state of flux. Their joint paper shifted the focus of biology from describing what organisms are to explaining how they become.

This realization was revolutionary because it removed the need for "purpose" in nature. It suggested that the diversity of life is the result of a blind, mechanical process. When Darwin published On the Origin of Species in 1859, he provided the evidence needed to move biology from a branch of natural history into a rigorous, predictive science.

Selection operates across different scales, from "selfish" genes to entire populations.

Selection operates across different scales, from "selfish" genes to entire populations.

While Darwin focused on the individual organism, modern biology recognizes that selection happens at multiple levels. The "gene-centered" view suggests that organisms are essentially vehicles used by genes to replicate themselves. If a gene causes an individual to sacrifice itself for its kin (who share that same gene), that gene can still spread through the population.

This multi-level selection explains complex social behaviors like altruism and cooperation. It also applies to modern challenges: we see natural selection in real-time as bacteria evolve resistance to antibiotics. The bacteria that survive the drugs aren't "stronger"; they simply possess the specific genetic sequence that allows them to bypass the medicine’s mechanism.

A diagram demonstrating mutation and selection

Aristotle considered whether different forms could have appeared, only the useful ones surviving.

Modern biology began in the nineteenth century with Charles Darwin's work on evolution by natural selection.

Part of Thomas Malthus's table of population growth in England 1780–1810, from his Essay on the Principle of Population, 6th edition, 1826

Charles Darwin noted that pigeon fanciers had created many kinds of pigeon, such as Tumblers (1, 12), Fantails (13), and Pouters (14) by selective breeding.

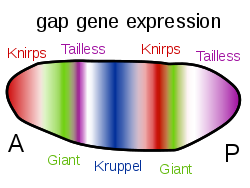

Evolutionary developmental biology relates the evolution of form to the precise pattern of gene activity, here gap genes in the fruit fly, during embryonic development.

During the Industrial Revolution, pollution killed many lichens, leaving tree trunks dark. A dark (melanic) morph of the peppered moth largely replaced the formerly usual light morph (both shown here). Since the moths are subject to predation by birds hunting by sight, the colour change offers better camouflage against the changed background, suggesting natural selection at work.

1: directional selection: a single extreme phenotype favoured.2, stabilizing selection: intermediate favoured over extremes.3: disruptive selection: extremes favoured over intermediate.X-axis: phenotypic traitY-axis: number of organismsGroup A: original populationGroup B: after selection

Different types of selection act at each life cycle stage of a sexually reproducing organism.

The peacock's elaborate plumage is mentioned by Darwin as an example of sexual selection, and is a classic example of Fisherian runaway, driven to its conspicuous size and coloration through mate choice by females over many generations.

Selection in action: resistance to antibiotics grows through the survival of individuals less affected by the antibiotic. Their offspring inherit the resistance.