Michel Foucault

Knowledge is not a neutral discovery; it is a primary tool for institutional power and social control.

Knowledge is not a neutral discovery; it is a primary tool for institutional power and social control.

Foucault’s central thesis was that power and knowledge are inextricably linked. He argued that society does not simply "find" truth; rather, institutions—such as schools, hospitals, and prisons—create systems of knowledge to categorize and regulate human behavior. By defining what is "normal" versus "abnormal," or "sane" versus "insane," those in power exert a form of social control that is often invisible because it is packaged as objective science or expert "truth."

He rejected the labels of structuralist or postmodernist, preferring to be seen as a critic of authority who refused to limit his own inquiry. His work suggests that we are governed not just by laws, but by the subtle "disciplining" of our bodies and minds through the very categories of identity we use to describe ourselves.

His methodology used "archaeology" and "genealogy" to expose history as a series of power shifts rather than steady progress.

His methodology used "archaeology" and "genealogy" to expose history as a series of power shifts rather than steady progress.

Foucault pioneered two distinct ways of looking at the past. His "archaeology" (seen in The Order of Things) treated history like a dig site, looking for the underlying "rules of thought" that allowed certain ideas to exist in one era but not another. He didn't see history as a straight line of improvement; instead, he saw it as a sequence of sudden shifts in how we organize knowledge.

Later, he adopted "genealogy," a technique inspired by Nietzsche. This method focused on the messy, often violent power struggles that birthed modern institutions. In Discipline and Punish, he traced how the public spectacle of torture was replaced by the "gentle" surveillance of the prison—not necessarily out of humanitarian progress, but because surveillance was a more efficient way to manage and "manufacture" obedient citizens.

Personal experiences with psychological distress and social taboos fueled his obsession with the "margins" of society.

Personal experiences with psychological distress and social taboos fueled his obsession with the "margins" of society.

Born into a prosperous family of surgeons, Foucault’s early life was defined by a rebellion against his father’s expectations and the rigid social conservatism of 1940s France. His time at the École Normale Supérieure was marked by brilliance but also extreme isolation and suicide attempts. These struggles were partially driven by the distress of navigating his homosexuality in a society where it was a deep taboo.

These private crises informed his professional focus. He spent his career defending those labeled "deviant" or "mad," seeing them not as broken individuals, but as people who revealed the limits and failures of society's rules. His fascination with the "macabre," torture, and extreme experiences was a way of exploring the edges of human existence that the mainstream sought to suppress.

His death from HIV/AIDS transformed him into a catalyst for public health activism and global awareness.

His death from HIV/AIDS transformed him into a catalyst for public health activism and global awareness.

Foucault's death in 1984 was a watershed moment for France. He was the first major public figure in the country to die from complications of HIV/AIDS. Because of his immense charisma and international stature, his death shattered the silence surrounding the pandemic, forcing a national conversation about a disease that had previously been ignored or stigmatized.

The impact of his death extended beyond his writings. His long-term partner, Daniel Defert, founded the charity AIDES in his memory, which became one of Europe’s most influential organizations in the fight against the virus. Even in death, Foucault’s life remained a critique of how society manages the body, identity, and the "other."

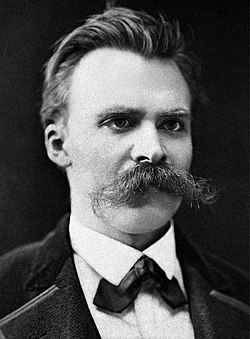

Image from Wikipedia

In the early 1950s, Foucault came under the influence of German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, who remained a core influence on his work throughout his life.

Foucault adored the work of Raymond Roussel and wrote a literary study of it.

Graves of Michel Foucault, his mother (right) and his father (left) in Vendeuvre-du-Poitou

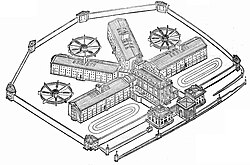

Image from Wikipedia