Martin Heidegger

Heidegger shifted the goal of philosophy from identifying "what" objects exist to questioning the very meaning of "Being."

Heidegger shifted the goal of philosophy from identifying "what" objects exist to questioning the very meaning of "Being."

Traditional philosophy treats "Being" as if it were just another entity or a list of properties. Heidegger argued that Western thought had forgotten the most fundamental question: What does it actually mean to be? He contended that before we can categorize objects or do science, we must examine the "pre-ontological" understanding we already have just by existing.

This "Question of Being" isn't an abstract logic puzzle; it is an investigation into how things become intelligible to us in the first place. By shifting focus from the object to the "sense" of being, Heidegger attempted to dismantle centuries of metaphysical assumptions and rebuild philosophy on the foundation of human experience.

Humans are not isolated observers, but "Dasein"—beings fundamentally defined by their immersion in the world.

Humans are not isolated observers, but "Dasein"—beings fundamentally defined by their immersion in the world.

Heidegger rejected the idea of the "mind" as a lonely island looking out at an external world. Instead, he coined the term Dasein ("being there") to describe the human condition. To be human is to be "being-in-the-world," a unitary state where we are always already involved in a web of relationships, tasks, and concerns.

We do not "encounter" the world as a collection of neutral facts; we "dwell" in it. Our existence is defined by "circumspection"—a way of looking at the world through the lens of our projects and possibilities. In this view, you aren't a subject observing a separate object; you are a participant in a "worldhood" where everything is connected by its relevance to your life.

The world reveals itself through practical use, becoming visible only when things "break" or fail.

The world reveals itself through practical use, becoming visible only when things "break" or fail.

Heidegger famously distinguished between two ways of encountering things: the "ready-to-hand" and the "present-at-hand." Most of the time, the tools we use are "transparent." When you use a fork to eat, you aren't thinking about the fork’s physical properties; it is an extension of your intent. It is "ready-to-hand"—effective, silent, and unnoticed.

The "present-at-hand" mode occurs when that tool breaks. If the fork snaps, it suddenly becomes a distinct "object" with properties (it is plastic, it is sharp, it is broken). Heidegger argued that theoretical, scientific analysis only happens when this practical flow is interrupted. Therefore, practical engagement with the world is more fundamental than scientific or detached observation.

His active support for the Nazi Party remains an indelible stain on his legacy and a challenge to his philosophy.

His active support for the Nazi Party remains an indelible stain on his legacy and a challenge to his philosophy.

In 1933, Heidegger became the rector of Freiburg University and joined the Nazi Party, a position he used to enthusiastically support the "German revolution" and Adolf Hitler. While he resigned the rectorate in 1934, he remained a member of the party until 1945. After the war, he was banned from teaching for several years during denazification hearings, eventually being classified as a Mitläufer (follower/associate).

The controversy lies in whether his philosophy is inherently linked to his politics. Critics argue his emphasis on "destiny," "rootedness," and the "critique of technology" provided a philosophical framework for nationalistic ideology. Heidegger’s 1966 interview with Der Spiegel, published posthumously, attempted to justify his actions but offered no explicit apology, leaving a permanent rift in his intellectual reception.

Despite his political disgrace, Heidegger’s "hermeneutics of life" shaped the landscape of modern thought.

Despite his political disgrace, Heidegger’s "hermeneutics of life" shaped the landscape of modern thought.

Heidegger’s influence is staggering, reaching far beyond pure philosophy into theology, psychology, and literary criticism. By synthesizing the "hermeneutics" of Dilthey with the "phenomenology" of his mentor Edmund Husserl, he created a new way of interpreting human existence. He moved away from rigid logic toward a "passionate affirmation" of individual being, heavily influenced by Kierkegaard and Nietzsche.

His list of students reads like a "who’s who" of 20th-century intellect, including Hannah Arendt, Hans-Georg Gadamer, and Herbert Marcuse. Even those who radically disagreed with his politics or his later "turn" toward poetry and the "essence of technology" found his deconstruction of the Western tradition impossible to ignore.

Image from Wikipedia

The Mesnerhaus in Meßkirch, where Heidegger grew up

Dilthey, c. 1855

View from Heidegger's vacation chalet in Todtnauberg. Heidegger wrote most of Being and Time there.

Title page of first edition of Being and Time

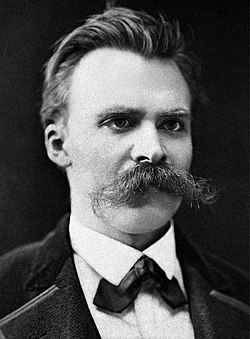

Heidegger dedicated many of his lectures to both Nietzsche and Hölderlin.

The University of Freiburg, where Heidegger was Rector from 21 April 1933 to 23 April 1934

Heidegger's grave in Meßkirch