Manhattan Project

Theoretical breakthroughs and wartime fear accelerated the leap from laboratory discovery to weaponized intent

Theoretical breakthroughs and wartime fear accelerated the leap from laboratory discovery to weaponized intent

The project was born from a decade of rapid-fire physics: James Chadwick discovered the neutron in 1932, and by 1938, German scientists had achieved nuclear fission. This created a terrifying theoretical possibility: a chain reaction that could level a city. Refugee scientists, particularly Leo Szilard and Albert Einstein, feared Nazi Germany would weaponize this first, prompting them to urge President Roosevelt to launch a domestic program.

Initially, the U.S. effort was fragmented and underfunded. It wasn't until the British "MAUD Committee" proved that a bomb was portable enough for a 1940s-era plane—and the 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor—that the U.S. committed the full weight of its industrial capacity. What began as a series of disparate university experiments at Columbia and Chicago quickly evolved into a high-priority military operation.

The Manhattan Project was less a scientific experiment and more a colossal $2 billion industrial construction race

The Manhattan Project was less a scientific experiment and more a colossal $2 billion industrial construction race

While history often focuses on the physicists, over 80 percent of the project’s $2 billion budget (roughly $28 billion today) was spent on infrastructure and material production. At its peak, the project employed nearly 130,000 people—roughly the population of Miami at the time—most of whom had no idea what they were building. The "Manhattan" name itself was a bureaucratic ruse; the project was officially the "Manhattan District" of the Army Corps of Engineers to hide its lack of geographic boundaries.

Major General Leslie Groves, who had just finished overseeing the construction of the Pentagon, ran the project with a focus on speed over cost. He bypassed traditional bidding and pushed for the simultaneous development of every potential method for fuel production. This "brute force" approach ensured that if one scientific path failed, others were already nearing completion.

Success required solving two distinct "fuel" problems at massive geographic scales

Success required solving two distinct "fuel" problems at massive geographic scales

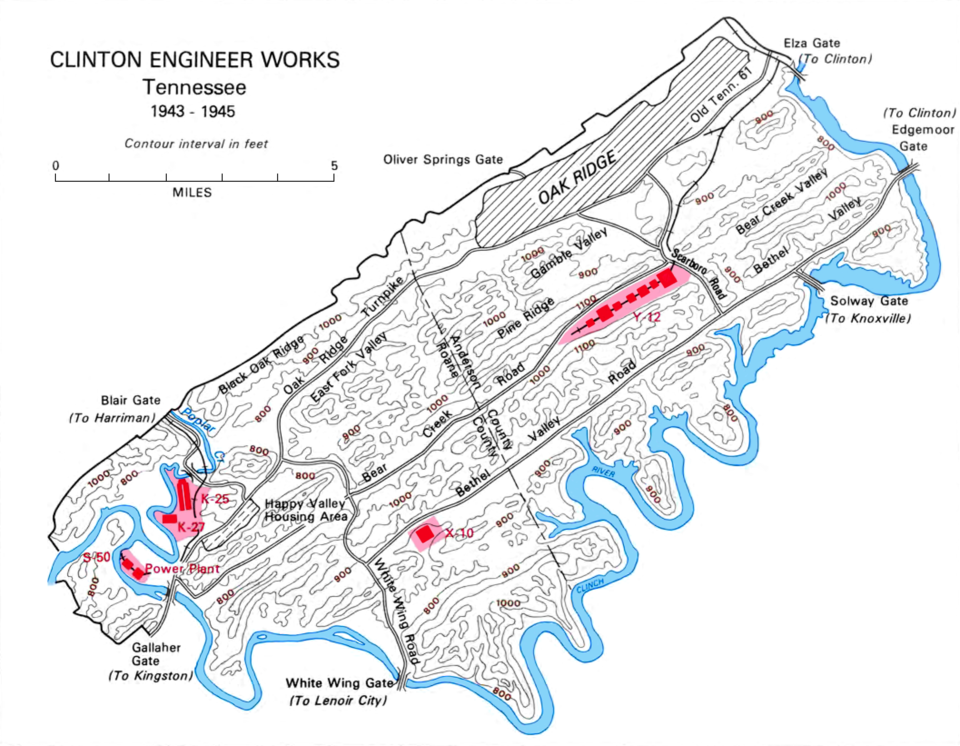

The project pursued two different elements for its bombs: Uranium-235 and Plutonium. Because these materials did not exist in nature in pure forms, the Army built secret cities to manufacture them. Enriched uranium was produced at the Clinton Engineer Works in Tennessee (Oak Ridge), while Plutonium was synthesized in the world's first industrial-scale nuclear reactors at the Hanford Engineer Works in Washington state.

This dual-track strategy was a massive gamble. The Tennessee facility used massive electromagnetic and diffusion plants to sift through tons of ore for tiny amounts of isotopes, while the Washington facility transformed the very nature of matter. These sites were supported by a global supply chain stretching from the mines of Canada to research labs in the United Kingdom.

A chemistry crisis in 1944 forced a desperate engineering pivot to the complex "implosion" design

A chemistry crisis in 1944 forced a desperate engineering pivot to the complex "implosion" design

The "Little Boy" bomb used a simple "gun-type" design—literally firing one piece of uranium into another. However, scientists discovered that Plutonium from the Hanford reactors was too "noisy" with impurities to work in a gun-type device; it would pre-detonate and fizzle. This discovery nearly derailed the project, as the simpler design was the primary plan.

To save the Plutonium program, Los Alamos Director J. Robert Oppenheimer pivoted to a much more complex "implosion" design for the "Fat Man" bomb. This required surrounding a plutonium core with precise "explosive lenses" that compressed it inward simultaneously. The design was so theoretical and risky that it required the Trinity Test—the first nuclear explosion in history—to prove it would actually work before it was used in combat.

Total wartime secrecy successfully tracked German progress while failing to stop Soviet infiltration

Total wartime secrecy successfully tracked German progress while failing to stop Soviet infiltration

The project operated under extreme compartmentalization, yet it faced two intelligence fronts. Operation Alsos saw Manhattan Project personnel following the front lines in Europe to seize German documents and scientists. They discovered that the German nuclear program was lagging far behind, hindered by a lack of resources and the flight of Jewish scientists.

Paradoxically, while the project was safe from German interference, it was deeply compromised by Soviet "atomic spies." Despite General Groves’ obsession with security, Soviet agents successfully penetrated Los Alamos, funneling critical design data back to the USSR. This intelligence significantly shortened the timeline for the Soviet Union to develop its own atomic bomb, setting the stage for the Cold War nuclear arms race.

Image from Wikipedia

Image from Wikipedia

Enrico Fermi, John R. Dunning, and Dana P. Mitchell in front of the cyclotron in the basement of Pupin Hall at Columbia University, 1940

March 1940 meeting at Berkeley, California: Ernest O. Lawrence, Arthur H. Compton, Vannevar Bush, James B. Conant, Karl T. Compton, and Alfred L. Loomis

Different fission bomb assembly methods explored during the July 1942 conference (sketches created in 1943 by Robert Serber)

Oppenheimer and Groves at the remains of the Trinity test in September 1945, two months after the test blast and just after the end of World War II. The white overshoes prevented fallout from sticking to the soles of their shoes.

Groves confers with James Chadwick, the head of the British Mission.

class=notpageimage| A selection of US and Canadian sites important to the Manhattan Project. Research and production took place at more than thirty sites across the US, the UK, and Canada. Click on the location for more information. Purple: Fissile material productionOrange: Feed materials productionGreen: ResearchBlack: Logistics/other

Shift change at the Y-12 uranium enrichment facility at the Clinton Engineer Works in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, on 11 August 1945. By May 1945, 82,000 people were employed at the Clinton Engineer Works. Photograph by the Manhattan District photographer Ed Westcott.

Some of the University of Chicago team that worked on the Chicago Pile-1, the first nuclear reactor, including Enrico Fermi and Walter Zinn in the front row and Harold Agnew, Leona Woods and Leó Szilárd in the second

Hanford workers collect their paychecks at the Western Union office.

A sample of a high-quality uranium-bearing ore (Tobernite) from the Shinkolobwe mine in Belgian Congo

A uranium metal "biscuit" created from the reduction reaction of the Ames process

Oak Ridge hosted several uranium separation technologies. The Y-12 electromagnetic separation plant is in the upper right. The K-25 and K-27 gaseous diffusion plants are in the lower left, near the S-50 thermal diffusion plant. The X-10 was for plutonium production.

Alpha I racetrack at Y-12