Mahatma Gandhi

Gandhi’s moral compass was forged through a blend of eclectic Hindu piety and childhood myths about absolute truth.

Gandhi’s moral compass was forged through a blend of eclectic Hindu piety and childhood myths about absolute truth.

Born into a Gujarati Hindu family, Gandhi’s early worldview was shaped by his mother, Putlibai, whose extreme devotion included long fasts and strict vows. This domestic piety was rooted in the Pranami tradition, a unique faith that integrated texts from the Bhagavad Gita, the Quran, and the Bible. This early exposure to religious pluralism laid the groundwork for his later vision of a multi-faith, independent India.

Beyond his family, Gandhi was haunted by Indian classics like the story of King Harishchandra, who sacrificed everything for the truth. He later admitted to acting out these stories "times without number" in his head. These legends turned "Truth" from an abstract concept into a supreme value that Gandhi believed must be lived out, eventually becoming the cornerstone of his political philosophy.

A paralyzing shyness and early professional failures nearly derailed his career before it began.

A paralyzing shyness and early professional failures nearly derailed his career before it began.

The man who would eventually lead millions was once a "tongue-tied" student who avoided all social interaction. As a young lawyer in London, his shyness was so acute that he joined a public speaking group just to function in his profession. Even after being called to the bar, his first attempt at a legal practice in Bombay was a disaster; he found himself psychologically unable to cross-examine witnesses and was forced to retreat to drafting simple petitions.

This period of "uncertain years" reveals a Gandhi who was far from a natural leader. His move to South Africa in 1893 wasn't a strategic choice for activism, but a desperate search for work after failing to establish himself in his homeland. It was only through the crucible of racial discrimination in South Africa that he transformed his personal reticence into the quiet, steely resolve of a master negotiator.

London transformed a simple vow of abstinence into a sophisticated philosophy of moral autonomy.

London transformed a simple vow of abstinence into a sophisticated philosophy of moral autonomy.

To gain his mother's permission to study abroad, Gandhi took a vow to abstain from meat, alcohol, and women. In London, this vow initially made him a social outlier, leaving him hungry and isolated. However, his search for vegetarian food led him to the London Vegetarian Society, where he met intellectuals who viewed vegetarianism not as a religious restriction, but as a moral and political choice.

This environment gave Gandhi his first taste of institutional politics. During a dispute in the Society regarding birth control (which Gandhi opposed), he defended a member’s right to disagree with the leadership, even though his own shyness prevented him from reading his own speech aloud. This era marked his transition from a man following his mother’s rules to a thinker who understood that personal discipline could be a tool for social change.

His political power was rooted in a radical identification with India’s rural poor.

His political power was rooted in a radical identification with India’s rural poor.

Upon returning to India, Gandhi abandoned the Western attire of a London-trained barrister for the short dhoti and hand-spun yarn (khadi). This wasn't merely a fashion choice; it was a sophisticated act of political communication. By adopting the lifestyle of the peasantry—living in self-sufficient communities and eating simple food—he bridged the gap between the elite Indian National Congress and the "common Indians" in the villages.

Gandhi’s methodology, Swaraj (self-rule), extended far beyond simple independence from Britain. He campaigned for women’s rights, the end of "untouchability," and religious amity. He used his own body as a political site, undertaking long fasts to stop communal violence and leading the 400 km Salt March to challenge British taxes. This "nonviolent resistance" effectively turned the British Empire’s own legal and moral frameworks against it.

Image from Wikipedia

Gandhi in 1876 at the age of 7

Gandhi (right) with his eldest brother Laxmidas in 1886

Commemorative plaque at 20 Baron's Court Road, Barons Court, London

Gandhi in London as a law student

Gandhi with the Vegetarian Society on the Isle of Wight, 1890

Gandhi and the founders of the Natal Indian Congress, 1895

Gandhi in South Africa, 1906

Gandhi (middle, third from right) with the stretcher-bearers of the Indian Ambulance Corps during the Boer War

Gandhi and his wife Kasturba (1902)

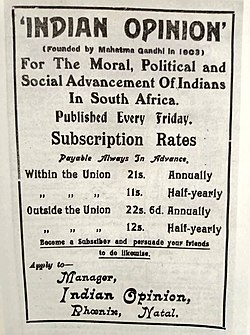

Advertisement of the Indian Opinion, a newspaper founded by Gandhi

Gandhi photographed in South Africa (1909)

Gandhi in 1918, at the time of the Kheda and Champaran Satyagrahas

Gandhi (wearing a Gandhi cap) with Rabindranath Tagore and Sharda Mehta, 1920

Gandhi with Annie Besant en route to a meeting in Madras in September 1921. Earlier, in Madurai, on 21 September 1921, Gandhi had adopted the loin-cloth for the first time as a symbol of his identification with India's poor.