Ludwig Wittgenstein

Born into an industrial dynasty, Wittgenstein’s early life was defined by immense wealth and a family tendency toward tragic self-destruction.

Born into an industrial dynasty, Wittgenstein’s early life was defined by immense wealth and a family tendency toward tragic self-destruction.

The Wittgensteins were the Austrian equivalent of the Carnegies, controlling a steel monopoly that made them the second-wealthiest family in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Their Vienna palace was a high-culture hub where Gustav Mahler and Johannes Brahms gave private concerts and Gustav Klimt painted family portraits. Despite this "atmosphere of humanity," the household was governed by a harsh, perfectionist father who demanded his sons become captains of industry.

This intense pressure likely contributed to a staggering family toll: three of Ludwig’s four brothers died by suicide. The eldest, Hans, a musical prodigy, disappeared from a boat in America; Rudi took his own life in a Berlin bar; and Kurt shot himself at the end of WWI when his troops deserted. Ludwig himself struggled with depression and a "disgust for life," eventually giving away his massive inheritance to his siblings to live a life of radical, almost ascetic, simplicity.

He authored two distinct philosophical eras, first attempting to "solve" philosophy through logic, then dismantling his own work through "language games."

He authored two distinct philosophical eras, first attempting to "solve" philosophy through logic, then dismantling his own work through "language games."

Wittgenstein is unique for having produced two masterpieces that contradict each other. His early work, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus (1921), argued that the structure of language mirrors the logical structure of the world. He believed that by defining the limits of what can be said clearly, he had solved all philosophical problems, leaving the rest to silence. He was so convinced of this that he quit philosophy for nearly a decade after its publication.

Upon his return to Cambridge in 1929, he began to reject his earlier logic-based assumptions. In his posthumously published Philosophical Investigations, he argued that the meaning of a word is not a fixed logical point, but rather its "use" within a specific "language game." This shift from formal logic to the messy, social reality of human communication redefined 20th-century thought, making Investigations arguably the most important philosophical text of its era.

Rejecting academic comfort, Wittgenstein lived a life of radical austerity as a soldier, schoolteacher, and hospital porter.

Rejecting academic comfort, Wittgenstein lived a life of radical austerity as a soldier, schoolteacher, and hospital porter.

Wittgenstein’s biography is a series of "escapes" from the ivory tower. During World War I, he volunteered for the Austrian army, serving on the front lines and winning multiple medals for bravery. It was in the trenches that he wrote much of the Tractatus. After the war, he worked as a primary school teacher in remote Austrian villages, though this ended in scandal after he used corporal punishment on a student—an event known as the Haidbauer incident.

Even as a world-renowned figure at Cambridge, he avoided the trappings of status. During World War II, he left his professorship to work as a hospital porter in London and a lab technician in Newcastle, keeping his identity secret from most of his coworkers. He viewed these periods of manual and menial labor as essential to his moral and mental health, often finding the "refined" atmosphere of academia stifling and "shallow."

He viewed every problem through a quasi-religious lens, demanding a precision in music and language that bordered on the pathological.

He viewed every problem through a quasi-religious lens, demanding a precision in music and language that bordered on the pathological.

Though he resisted organized religion and struggled to "bend the knee" to dogma, Wittgenstein famously stated, "I cannot help seeing every problem from a religious point of view." This manifest as a grueling quest for honesty and clarity. He was obsessed with music—possessing absolute pitch and the ability to whistle entire concertos—but he felt classical music "stopped with Brahms," viewing later developments as the "noise of machinery."

This demand for absolute integrity made him a terrifying figure to many of his peers. He saw philosophy not as a set of theories, but as a "battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language." For Wittgenstein, clarity wasn't just an intellectual goal; it was a moral imperative. He believed that failing to use language precisely was not just a mistake, but a form of personal failure.

Image from Wikipedia

Karl Wittgenstein was one of the richest men in Europe.

Palais Wittgenstein, the family home, around 1910

Ludwig, c. 1890s

Ludwig sitting in a field as a child

From left, Helene, Rudi, Hermine, Ludwig (the baby), Gretl, Paul, Hans, and Kurt, around 1890

Ludwig (bottom-right), Paul, and their sisters, late 1890s

The Realschule in Linz

Austrian philosopher Otto Weininger (1880–1903)

Class photograph at the Realschule in 1901, a young Adolf Hitler in the back row on the right. In the penultimate row, third from the right, a student who is believed to be Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Ludwig Wittgenstein, aged about eighteen

The old Technische Hochschule Berlin in Charlottenburg, Berlin

Wittgenstein with his friend William Eccles at the Kite-Flying Station in Glossop, Derbyshire, Summer 1908

Wittgenstein, 1910s

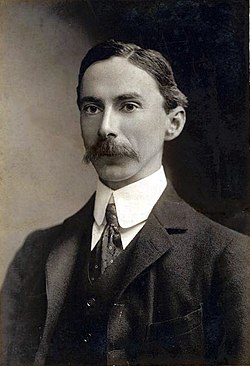

Bertrand Russell, 1907