Louisiana Purchase

The United States acquired an empire for three cents an acre, doubling the nation's size in a single stroke.

The United States acquired an empire for three cents an acre, doubling the nation's size in a single stroke.

The 1803 purchase was one of history's most lopsided real estate deals. For $15 million—roughly $380 million in today’s currency—the U.S. acquired 828,000 square miles of territory. This massive tract spanned from the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains, eventually forming all or part of 15 states and two Canadian provinces. It effectively moved the American border from the edges of the original colonies into the heart of the continent, encompassing the entire Mississippi River drainage basin.

The acquisition was a demographic and economic transformation. At the time of the sale, the territory housed roughly 60,000 non-native inhabitants, half of whom were enslaved Africans. By securing this land, the U.S. gained total control of the Mississippi River, the vital "superhighway" for Western farmers to get their produce to global markets via the port of New Orleans.

Napoleon’s defeat in the Caribbean turned a French colonial dream into an urgent fire sale.

Napoleon’s defeat in the Caribbean turned a French colonial dream into an urgent fire sale.

The purchase was not the result of American brilliance alone, but of French failure. Napoleon Bonaparte originally intended to use the Louisiana Territory as a granary for a revived French empire in the New World, centered on the profitable sugar colony of Saint-Domingue (Haiti). However, a massive slave revolt led by Toussaint Louverture and a devastating outbreak of yellow fever decimated French forces. With his Caribbean army destroyed and a renewed war against Great Britain looming, Napoleon realized Louisiana was a liability he could not defend.

Napoleon’s decision to sell was a strategic pivot to fund his European wars and spite his rivals. By selling to the United States, he ensured the territory would not fall into British hands and hoped to create a maritime rival to England that would "sooner or later, humble her pride." He famously offered the entire territory to American negotiators who had only come to buy a single city.

A mission to secure one port city accidentally secured the heart of the continent.

A mission to secure one port city accidentally secured the heart of the continent.

President Thomas Jefferson originally sent James Monroe and Robert Livingston to Paris with a narrow, $10 million mandate: buy New Orleans and the surrounding Florida panhandle. Control of the mouth of the Mississippi was essential for national security, as Spain had recently revoked the "right of deposit" for American merchants. The American representatives were "dumbfounded" when French Treasury Minister Barbé-Marbois offered them the entire Louisiana Territory for just $15 million.

Livingston and Monroe recognized the offer was too good to pass up, even though they lacked the legal authority to spend that much or acquire that much land. They signed the treaty quickly, fearing Napoleon might change his mind. Upon signing, Livingston remarked, "From this day the United States take their place among the powers of the first rank."

Jefferson abandoned his strict legal principles to protect the nation’s future.

Jefferson abandoned his strict legal principles to protect the nation’s future.

The purchase triggered a constitutional crisis for Thomas Jefferson. As a "strict constructionist," Jefferson believed the federal government only had the powers specifically listed in the Constitution—and the power to buy foreign land wasn't there. He briefly considered a constitutional amendment to authorize the deal but dropped it when advisors warned that Napoleon might withdraw the offer during the delay. Jefferson ultimately rationalized the purchase as a "guardian" acting for the good of his ward.

Opposition was fierce but largely partisan. Federalists in New England feared the new Western lands would create an agricultural power base that would dilute the influence of Northern bankers and merchants. They also worried about the expansion of slavery and the eventual "disunion" of the country. Despite a narrow 59–57 vote in the House to deny funding, the treaty was ratified, marking a permanent shift toward executive power in American history.

The treaty sold a "preemptive right" to land that France did not actually control.

The treaty sold a "preemptive right" to land that France did not actually control.

While the maps showed a massive transfer of territory, the reality on the ground was different. France only occupied a tiny fraction of the 530 million acres involved; the vast majority was owned and inhabited by Native American nations. Effectively, the United States did not buy the land itself, but rather the "preemptive right" to obtain that land from Indigenous peoples through treaty or conquest, to the exclusion of other European powers.

This legal distinction set the stage for decades of conflict and displacement. By claiming "sovereignty" over the region, the U.S. government asserted its sole right to manage the "Indian Question" west of the Mississippi. The purchase transformed the U.S. from a coastal republic into a colonial power, initiating a century of westward expansion that would systematically dismantle Native sovereignty.

Image from Wikipedia

An 1804 map of "Louisiana", bounded on the west by the Rocky Mountains

The future president James Monroe as envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary to France helped Robert R. Livingston in negotiating the Louisiana Purchase.

The original treaty of the Louisiana Purchase

Transfer of Louisiana by Ford P. Kaiser for the Louisiana Purchase Exposition (1904)

Flag raising in the Place d'Armes (now Jackson Square), New Orleans, marking the transfer of sovereignty over French Louisiana to the United States, December 20, 1803, as depicted by Thure de Thulstrup in 1902

Issue of 1953, commemorating the 150th anniversary of signing

Share issued by Hope & Co. in 1804 to finance the Louisiana Purchase

The Purchase was one of several territorial additions to the U.S.

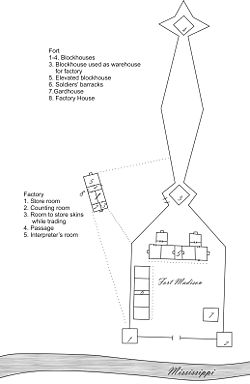

Plan of Fort Madison, built in 1808 to establish U.S. control over the northern part of the Louisiana Purchase, drawn 1810

Louisiana Purchase territory shown as American Indian land in Gratiot's map of the defenses of the western & north-western frontier, 1837