Logic

Logic functions as the "physics" of reasoning, focusing on structure over content.

Logic functions as the "physics" of reasoning, focusing on structure over content.

Logic is the study of how conclusions follow from premises. It isn't concerned with whether a specific claim is true in the real world (like "Mars is red"), but rather whether the connection between two claims holds water. This makes logic "topic-neutral." It examines the skeleton of an argument—the way ideas are linked—independent of the subject matter.

An argument is considered correct if the premises provide sufficient support for the conclusion. This "support" is the central focus of the field. By studying these structures, logicians create theoretical frameworks to distinguish between valid reasoning and fallacies, which are errors in the logic that lead to incorrect conclusions even if the individual facts seem plausible.

Formal logic uses symbolic "math" to eliminate the ambiguity of human language.

Formal logic uses symbolic "math" to eliminate the ambiguity of human language.

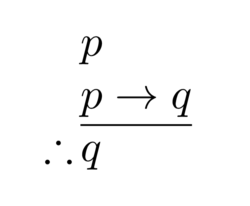

Because natural language is messy, vague, and context-dependent, formal logic (or symbolic logic) replaces words with abstract symbols. By stripping away "concrete content," logicians can test the validity of an argument as if it were a mathematical equation. For example, the rule of modus ponens states that if you have "p" and "if p then q," you must have "q," regardless of what p and q actually represent.

This symbolic approach allows for the discovery of "logical truths." A proposition is logically true if it remains true under every possible interpretation of its parts—it is true in all possible worlds. A classic example is the statement "either it is raining, or it is not." The internal structure of the sentence makes it impossible to be false, no matter the weather.

Informal logic bridges the gap between rigid formulas and everyday human discourse.

Informal logic bridges the gap between rigid formulas and everyday human discourse.

While formal logic is precise, it struggles with the nuances of daily life. Informal logic was developed to analyze "natural language" arguments directly. It deals with critical thinking and the psychology of argumentation. It doesn't just look at the math of the sentence; it looks at the meaning of substantive concepts and the context in which they are said.

This branch is where we find the study of informal fallacies—errors in reasoning that depend on the content of the argument rather than just the form. For example, a "false dilemma" (e.g., "you are either with us or against us") is a failure of logic because it unfairly excludes other viable options, a nuance that a purely symbolic system might miss.

Our thinking fluctuates between the absolute certainty of deduction and the "best guesses" of induction.

Our thinking fluctuates between the absolute certainty of deduction and the "best guesses" of induction.

Deductive arguments offer the strongest possible support: if the premises are true, the conclusion must be true. It is "truth-preserving," meaning it never leads from truth to falsehood. However, deduction doesn't actually provide new information; it simply reveals what was already hidden within the premises.

To expand our knowledge, we use "ampliative" arguments, which include induction and abduction. Inductive reasoning uses patterns to make generalizations (e.g., "every raven I've seen is black, so all ravens are black"). Abductive reasoning is "inference to the best explanation," like a doctor diagnosing a disease based on symptoms. These methods are essential for science and daily life, though they only provide probability, never 100% certainty.

Logic studies valid forms of inference like modus ponens.

Argument terminology used in logic

Young America's dilemma: Shall I be wise and great, or rich and powerful? (poster from 1901). This is an example of a false dilemma: an informal fallacy using a disjunctive premise that excludes viable alternatives.

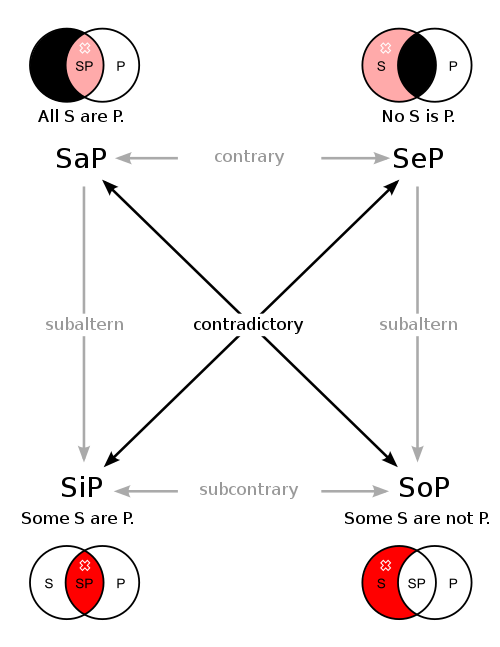

The square of opposition is often used to visualize the relations between the four basic categorical propositions in Aristotelian logic. It shows, for example, that the propositions "All S are P" and "Some S are not P" are contradictory, meaning that one of them has to be true while the other is false.

Bertrand Russell made various contributions to mathematical logic.

Conjunction (AND) is one of the basic operations of Boolean logic. It can be electronically implemented in several ways, for example, by using two transistors.

Top row: Aristotle, who established the canon of western philosophy; and Avicenna, who replaced Aristotelian logic in Islamic discourse. Bottom row: William of Ockham, a major figure of medieval scholarly thought; and Gottlob Frege, one of the founders of modern symbolic logic.