Lewis and Clark Expedition

Thomas Jefferson envisioned the expedition as a strategic race for sovereignty rather than a purely scientific quest.

Thomas Jefferson envisioned the expedition as a strategic race for sovereignty rather than a purely scientific quest.

While the journals of the Corps of Discovery are celebrated for their biological and geographic records, the mission's primary driver was geopolitical. Following the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, Jefferson was desperate to establish an American presence in the West before British or Spanish interests could solidify their claims. He specifically sought a "practicable water communication" across the continent to dominate the lucrative fur trade and secure a commercial gateway to the Pacific.

To bolster the legal weight of the American claim, Jefferson prioritized the gathering of scientific data. He understood that "discovery" in the eyes of European powers was strengthened by detailed mapping and the classification of new species. Thus, every plant pressed and every latitude recorded was a brick in the wall of American territorial legitimacy.

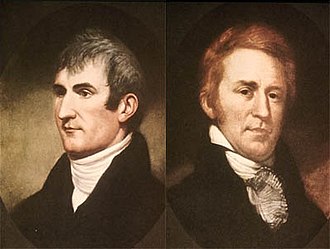

Meriwether Lewis underwent a multidisciplinary "crash course" to become Jefferson’s eyes, ears, and hands in the wilderness.

Meriwether Lewis underwent a multidisciplinary "crash course" to become Jefferson’s eyes, ears, and hands in the wilderness.

Jefferson did not simply choose a soldier; he molded a polymath. Before setting out, Lewis was sent to Philadelphia to study under the nation's leading minds. He learned medicinal cures from Benjamin Rush, celestial navigation from Andrew Ellicott, and specimen preservation from Caspar Wistar. This intellectual rigors was necessary because Lewis would be the expedition's primary doctor, botanist, and cartographer in a region thousands of miles from any laboratory.

The expedition’s logistics were equally meticulously planned, featuring a blend of high-tech and high-volume supplies. They carried a sophisticated .46 caliber Girandoni air rifle—a silent, repeating weapon meant to impress tribes with American military "magic"—alongside 193 pounds of "portable soup" and 30 gallons of strong spirits. Even Lewis’s choice of a Newfoundland dog, Seaman, was strategic; the animal served as both a hunter and a nocturnal sentry against predators.

The expedition’s greatest physical hurdle was born from a geographic myth regarding the Rocky Mountains.

The expedition’s greatest physical hurdle was born from a geographic myth regarding the Rocky Mountains.

The Corps of Discovery operated under the tragic misconception that the "Stony Mountains" were a narrow, easily portaged ridge similar to the Appalachians. This belief was fueled by accounts like those of Moncacht-Apé, which suggested one could simply carry boats from the Missouri’s headwaters to a westward-flowing river. In reality, the expedition was blindsided by the sheer scale and brutality of the Bitterroot Range.

The search for the "Northwest Passage"—a navigable water route to the Pacific—ended in the realization that it simply did not exist. Instead of a simple portage, the crew faced a grueling mountain crossing that required them to abandon their keelboats for horses and eventually canoes, relying entirely on Shoshone and Nez Perce knowledge to avoid starvation.

Diplomatic success rested on a "Peace Medal" policy and the vital linguistic bridge provided by Sacagawea.

Diplomatic success rested on a "Peace Medal" policy and the vital linguistic bridge provided by Sacagawea.

Interaction with Native American nations was the expedition's most consistent challenge. To signal intent, they distributed "Indian Peace Medals" bearing Jefferson’s likeness, symbolizing a new era of U.S. sovereignty. While they nearly came to blows with the Lakota (Teton Sioux) over river tolls and trade rights, most encounters were defined by a mutual, if tense, necessity for trade and information.

The presence of Sacagawea, a Shoshone woman, was perhaps the expedition’s greatest diplomatic asset. As a woman traveling with a large group of armed men, her presence signaled to wary tribes that the party was not a war party. Furthermore, her ability to translate through a complex chain of languages—from Shoshone to Hidatsa to French to English—allowed Lewis and Clark to negotiate for the horses and guides that ultimately saved the mission.

Reaching the Pacific necessitated a rare moment of democratic inclusion among social unequals.

Reaching the Pacific necessitated a rare moment of democratic inclusion among social unequals.

Upon reaching the mouth of the Columbia River in late 1805, the expedition faced a critical decision: where to build their winter quarters. In a move that defied the rigid social hierarchies of the 19th-century United States, the leadership held a vote. Every member of the party was allowed a say, including York, an enslaved man owned by Clark, and Sacagawea.

This moment of "frontier democracy" led to the construction of Fort Clatsop on the south side of the river. However, the winter was "dismal," characterized by constant rain, rotting clothes, and a lack of food as the elk populations retreated. Despite the physical misery of the Pacific coast, the group successfully turned for home in March 1806, arriving back in St. Louis as national heroes who had mapped the blueprint for a transcontinental nation.

Image from Wikipedia

Camp Dubois (Camp Wood) reconstruction, where the Corps of Discovery mustered on the east side of the Mississippi River, through the winter of 1803–1804, to await the transfer of the Louisiana Purchase to the United States

Corps of Discovery meet Chinooks on the Lower Columbia, October 1805 (Lewis and Clark on the Lower Columbia painted by Charles Marion Russel, c. 1905)

Reconstruction of Fort Mandan, Lewis and Clark Memorial Park, North Dakota

Lewis and Clark meeting the Bitterroot Salish at Ross Hole, September 4, 1805

Fort Clatsop reconstruction on the Columbia River near the Pacific Ocean

Map of Lewis and Clark's expedition: It changed mapping of northwest America by providing the first accurate depiction of the relationship of the sources of the Columbia and Missouri Rivers, and the Rocky Mountains around 1814

Statue of Sacagawea, a Shoshone woman who accompanied the Lewis and Clark Expedition

Painting of Mandan Chief Big White, who accompanied Lewis and Clark on their return from the expedition

Lewis and Clark Expedition 150th anniversary issue, 1954

Lewis and Clark were honored (along with the American bison) on the Series of 1901 $10 Legal Tender

Lewis and Clark Interpretive Center in Cape Disappointment State Park

Lewis and Clark statue (with Seaman (dog)) in St. Charles, Missouri

Lewis and Clark Mosaic image in Missouri