Karl Marx

Marx "flipped" Hegelian philosophy to argue that physical reality—not abstract ideas—drives human history.

Marx "flipped" Hegelian philosophy to argue that physical reality—not abstract ideas—drives human history.

While studying in Berlin, Marx joined the "Young Hegelians," a group of radicals who used the dialectical methods of G.W.F. Hegel to challenge religion and politics. While Hegel believed history was the unfolding of "Spirit" or ideas, Marx eventually rejected this as "standing on its head." He argued that the way we produce the things we need to survive (food, shelter, tools) forms the real foundation of society.

This shift, known as historical materialism, suggests that the "superstructure" of a culture—its laws, religion, and government—is actually a reflection of its economic base. In Marx's view, you cannot understand a society's values without first understanding who owns the factories and who works the fields.

History is a series of "class struggles" where the friction between owners and workers inevitably triggers revolution.

History is a series of "class struggles" where the friction between owners and workers inevitably triggers revolution.

Marx’s most famous insight is that human history is defined by the conflict between those who own the "means of production" (the bourgeoisie) and those who must sell their labor to survive (the proletariat). In a capitalist system, the bourgeoisie profits by paying workers less than the full value of their labor—a gap Marx identified as "surplus value."

He didn't just see this as unfair; he saw it as unsustainable. He predicted that capitalism would produce internal "tensions"—such as recurring economic crises and the concentration of wealth—that would eventually force the working class to develop "class consciousness." This realization would lead the proletariat to seize power, abolish private property, and establish a classless, communist society.

A life of intellectual exile was sustained by a singular partnership with Friedrich Engels.

A life of intellectual exile was sustained by a singular partnership with Friedrich Engels.

Marx’s radicalism made him a man without a country. He was expelled from Prussia, France, and Belgium, eventually spending the final 34 years of his life in London. Throughout this period of poverty and statelessness, he relied heavily on Friedrich Engels, a wealthy factory heir who shared his revolutionary goals. Engels was more than a benefactor; he was a collaborator who co-authored The Communist Manifesto and edited the final volumes of Das Kapital after Marx’s death.

While in London, Marx lived a dual life. He spent his days in the British Museum Reading Room conducting an exhaustive autopsy of the capitalist system, and his nights involved in the "First International," an association of workers' parties. Despite his massive intellectual output, he was often in financial ruin, saved only by Engels’ constant checks and his own occasional work as a journalist.

His blueprints for sociology and economics became the dominant political reality of the 20th century.

His blueprints for sociology and economics became the dominant political reality of the 20th century.

Marx is rarely viewed neutrally; he is cited as one of the three principal architects of modern social science (alongside Durkheim and Weber), yet his name is inextricably linked to the 20th-century regimes that claimed his mantle. Marxism-Leninism became the guiding ideology for revolutions across the globe, leading to the formation of communist states that governed a third of the world's population at their peak.

Modern economists and sociologists still use Marx’s "conflict theory" to analyze inequality, globalization, and the relationship between labor and capital. Even for those who reject his solutions, Marx remains the essential critic of capitalism, correctly identifying its tendency toward boom-and-bust cycles and its power to turn every human relation into a financial transaction.

Black-and-white portrait photograph of Marx sitting

Marx's birthplace, now Brückenstraße 10, in Trier. The family occupied two rooms on the ground floor and three on the first floor. Purchased by the Social Democratic Party of Germany in 1928, it now houses a museum devoted to him.

Jenny von Westphalen in the 1830s

Trierer students in front of the White Horse, among them, Karl Marx

Inscription at the University of Jena commemorating the PhD he was awarded there in 1841

Doctoral certificate for Karl Marx from the University of Jena, 15 April 1841

Friedrich Engels, whom Marx met in 1844; the two became lifelong friends and collaborators.

Marx (right) with his daughters and Engels

The first edition of The Manifesto of the Communist Party, published in German in 1848

Marx lived at 28 Dean Street, Soho, London from 1851 to 1856. An English Heritage Blue plaque is visible on the second floor.

Earliest known photograph taken of Marx in London, 1861.

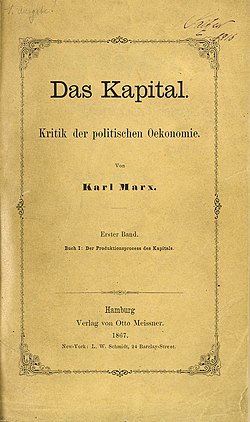

The first volume of Das Kapital

Photo of Marx, 1875

Marx in 1882

Jenny Carolina and Jenny Laura Marx (1869): all the Marx daughters were named Jenny in honour of their mother, Jenny von Westphalen.