Italian cuisine

Simplicity is a deliberate choice of quality over complexity

Simplicity is a deliberate choice of quality over complexity

Italian cuisine is defined by its restraint. Unlike many haute cuisines that rely on complex techniques or heavy sauces, Italian cooking typically features dishes with very few ingredients. This places the burden of flavor entirely on the quality of the raw materials—the ripeness of a tomato, the press of the olive oil, or the age of a cheese—rather than the artifice of the preparation.

Because many of these recipes were developed by ordinary people for daily home cooking rather than by professional chefs for royal courts, they prioritize seasonality and regional availability. This "peasant" lineage has proven incredibly resilient; today, it drives a global turnover of more than €200 billion and was recognized as UNESCO intangible cultural heritage in 2025.

Global trade and conquest provided the "traditional" building blocks

Global trade and conquest provided the "traditional" building blocks

The ingredients now synonymous with Italy are largely "immigrants" that arrived via trade and colonization. The Arabs introduced spinach, rice, and citrus to Sicily in the 9th century, along with the durum wheat used for pasta. Before the colonization of the Americas, Italian cuisine existed entirely without tomatoes, potatoes, capsicums, or maize—staples that only took a central role in the last few hundred years.

Even ancient influences were imported: the Romans brought in cherries, apricots, and peaches from abroad, while employing Greek bakers to refine their breads. This history reframes Italian cuisine not as a static tradition, but as a masterclass in culinary "localization"—taking foreign imports and weaving them so deeply into the regional fabric that they became inseparable from the national identity.

Regional fragmentation preceded the concept of a national menu

Regional fragmentation preceded the concept of a national menu

Italy did not exist as a unified state until the 19th century, and its cuisine remains a collection of distinct regional gastronomies. For centuries, geography and politics created isolated "food bubbles": Milan became the capital of risottos, Bologna the home of tortellini, and Naples the birthplace of pizza. These cities developed their own techniques based on their specific proximity to the sea or their position along the Silk Road.

Modern Italian cuisine is characterized by a "continuous exchange" between these regions. Dishes that were once hyper-local have proliferated throughout the country, but they rarely become standardized. Instead, they exist as a web of variations, where a single pasta shape or sauce might change names and ingredients every few miles.

Culinary literature evolved from royal excess to domestic science

Culinary literature evolved from royal excess to domestic science

Early Italian cookbooks, such as Bartolomeo Scappi’s 1570 Opera, were written for the high courts and the Papacy, focusing on elaborate banquets and specialized kitchen tools. However, by the 18th and 19th centuries, the focus shifted toward the "bourgeois housewife." Authors began writing for modest households, emphasizing "Pythagorean food" (plant-based diets) and regional economy over courtly grandeur.

The definitive turning point came in 1891 with Pellegrino Artusi’s The Science of Cooking and the Art of Eating Well. Artusi’s work is considered the canon of modern Italian cuisine because it was the first to successfully synthesize disparate regional recipes into a single, cohesive national identity. It moved the "soul" of Italian cooking out of the palace and permanently into the home kitchen.

Clockwise from top left; some of the most popular Italian foods: Neapolitan pizza, carbonara, espresso, and gelato

A Roman mosaic depicting a banquet during a hunting trip, from the Late Roman Villa Romana del Casale, Sicily

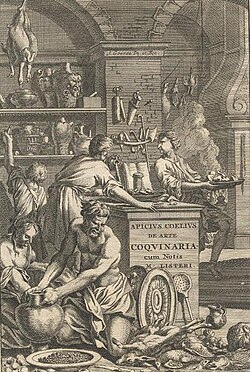

Apicius, De re coquinaria (On the Subject of Cooking), 1709 edition

A restored medieval kitchen inside Verrucole Castle, Tuscany

The oldest restaurant in Italy, Antica trattoria Bagutto in Milan, dates to at least 1284.

Bartolomeo Scappi, personal chef to Pope Pius V

Bucatini with amatriciana sauce, which includes the New World vegetable tomato

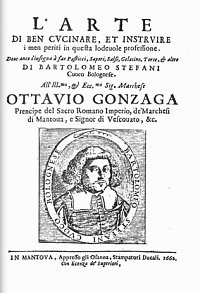

L'arte di ben cucinare (The Art of Well Cooking), published by Bartolomeo Stefani in 1662

Italian products labelled with protected status. The wines are labelled DOCG and DOC, the prosciutto di San Daniele is labelled PDO.

Pesto, a Ligurian sauce made with basil, olive oil, hard cheese, and pine nuts, which can be eaten with pasta or other dishes such as soup

Parmigiano Reggiano cheese

Olive oil

Various types of pasta

The ingredients of traditional pizza Margherita—tomatoes (red), mozzarella (white), and basil (green)—are held by popular legend to be inspired by the colours of the national flag of Italy.

Barrels of aging balsamic vinegar