Industrial Revolution

A fundamental shift from hand-powered craft to mechanized factory systems permanently broke the ceiling on human productivity.

A fundamental shift from hand-powered craft to mechanized factory systems permanently broke the ceiling on human productivity.

The Industrial Revolution was the Great Pivot of human history—the moment society moved from organic, animal-based energy to the "mechanized factory system." Before this, manufacturing was a slow, "putting-out" process where families spun wool at home. By 1760, Britain began a transition toward water and steam power, chemical manufacturing, and machine tools. This shift wasn't just about faster production; it was about stability. For the first time, output could scale consistently, leading to the first era of sustained per-capita economic growth in human history.

The textile industry was the vanguard of this movement. Cotton production moved from households into massive mills, where innovations like the spinning jenny and water frame allowed a single worker to produce as much as 500 hand-spinners once could. This efficiency turned textiles into the world's first dominant modern industry, commanding the lion's share of global investment and employment.

Britain’s dominance was fueled by a perfect storm of colonial trade, legal protections for property, and an abundance of coal and iron.

Britain’s dominance was fueled by a perfect storm of colonial trade, legal protections for property, and an abundance of coal and iron.

Britain didn't industrialize by accident; it possessed a unique "cocktail" of requirements. Geographically, it sat on massive deposits of coal and iron, providing the fuel and the bones for new machinery. Politically, the British legal system began favoring property rights and business growth, creating a stable environment for entrepreneurs. Crucially, the British Agricultural Revolution had already increased food production, freeing up a massive labor force that was no longer tied to the soil and could instead staff the new urban factories.

The British Empire provided the necessary scale. By the mid-18th century, Britain controlled a global trading network stretching from North America to India. This empire functioned as both a source of raw materials (like slave-grown cotton from the Americas) and a captive market for finished goods. The "entrepreneurial spirit" cited by historians was backed by the sheer muscle of a global commercial hegemony.

The trio of mechanized textiles, efficient steam power, and refined iron production formed the technical scaffolding of the modern world.

The trio of mechanized textiles, efficient steam power, and refined iron production formed the technical scaffolding of the modern world.

The revolution was driven by a handful of high-impact technological gains. Steam power was the most transformative; as engines became more efficient—using up to 90% less fuel than early models—they were adapted for "rotary motion," meaning they could power anything from a factory loom to a locomotive. This decoupled industry from rivers, allowing factories to be built anywhere.

Simultaneously, the iron industry abandoned charcoal for coke (processed coal), which allowed for much larger blast furnaces and cheaper, stronger structural iron. This feedback loop was completed by the invention of precision machine tools—lathes and milling machines. These allowed for the manufacture of interchangeable metal parts, moving the world away from one-off artisanal objects toward the era of mass production and the Second Industrial Revolution.

While the revolution triggered a massive population explosion, its immediate impact on the common worker remains a subject of intense historical debate.

While the revolution triggered a massive population explosion, its immediate impact on the common worker remains a subject of intense historical debate.

Economists agree that the Industrial Revolution is the most significant event in material history since the invention of agriculture. Before this era, GDP per capita was essentially flat; afterward, it began a vertical climb. This wealth creation supported an unprecedented rise in population and, eventually, a significant increase in the standard of living across the Western world.

However, the "insight-per-minute" here is the timing of that prosperity. While some historians argue that the standard of living began to rise immediately, others contend that the benefits didn't reach the average person until the 20th century. For many early workers, the "revolution" meant grueling factory hours and a recession in the 1830s as markets matured. The "Great Divergence" also began here, as the West’s industrial leap left previously dominant economies in India and China behind.

The term "Industrial Revolution" was a retrospective label used to frame a gradual evolutionary process as a sudden, violent upheaval.

The term "Industrial Revolution" was a retrospective label used to frame a gradual evolutionary process as a sudden, violent upheaval.

The people living through the early 1760s didn't call it a "revolution." The term wasn't popularized until 1881 by historian Arnold Toynbee, over a century after it began. While we often think of it as a sudden explosion of English genius, many modern historians argue that "proto-industrialization" in the Islamic world, Mughal India, and China had already laid the groundwork. They suggest the "revolution" was actually a gradual acceleration of existing trends.

Even the timeline is contested. Some argue Britain was already industrializing in the 1600s, while others, like Eric Hobsbawm, claim the shift wasn't truly "felt" until the 1830s. This debate highlights a key insight: technological change is often quiet and incremental at first, only appearing as a "revolution" once the old social order has been completely dismantled and replaced.

Weaving with handlooms from William Hogarth's Industry and Idleness in 1747

John Lombe's silk mill site today in Derby, rebuilt as Derby Silk Mill

European colonial empires at the start of the Industrial Revolution, superimposed upon modern political boundaries

Weaver in Nuremberg, c. 1524

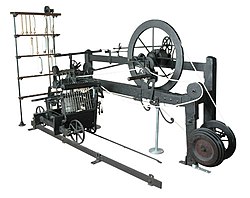

A model of the spinning jenny in a museum in Wuppertal. Invented by James Hargreaves in 1764, the spinning jenny was one of the innovations that started the revolution.

The only surviving example of a spinning mule built by the inventor Samuel Crompton, the mule produced high-quality thread with minimal labour, now on display at Bolton Museum in Greater Manchester

The interior of Marshall's Temple Works in Leeds, West Yorkshire

The reverberatory furnace could produce cast iron using mined coal; the burning coal is separated from the iron to prevent constituents of the coal, such as sulfur and silica, from becoming impurities in the iron. Iron production increased due to the ability to use mined coal directly.

The Iron Bridge in Shropshire, England, the world's first bridge constructed of iron, opened in 1781.

Horizontal (lower) and vertical (upper) cross-sections of a single puddling furnace

A Watt steam engine, invented by James Watt, who transformed the steam engine from a reciprocating motion that was used for pumping to a rotating motion suited to industrial applications; Watt and others significantly improved the efficiency of the steam engine.

Newcomen's steam-powered atmospheric engine was the first practical piston steam engine; subsequent steam engines were to power the Industrial Revolution.

Maudslay's early screw-cutting lathes, developed in the late 1790s

The Thames Tunnel, which opened in 1843; portland cement concrete was used in the world's first underwater tunnel.

The Crystal Palace housed the Great Exhibition of 1851