Indian cuisine

Indian cuisine rests on an 8,000-year foundation of agricultural continuity and early global trade.

Indian cuisine rests on an 8,000-year foundation of agricultural continuity and early global trade.

The flavors of the modern Indian plate began in the Neolithic Revolution. By 7000 BCE, wheat and barley were cultivated in the Indus Valley; by 3000 BCE, the region was already harvesting what we now consider "quintessential" spices: turmeric, cardamom, black pepper, and mustard. This wasn't an isolated development. Evidence shows that by 2350 BCE, the Indus Valley (Meluhha) was trading timber and ivory with Mesopotamia, while clove heads from Maritime Southeast Asia were finding their way into Indian kitchens nearly 4,000 years ago.

This deep history is reflected in the continuity of staples. Pearl millet (bajra) has been cultivated in the subcontinent since 6200 BCE. Ancient texts like the Mahabharata and the Yājñavalkya Smṛti even provide early records of "pulao" (rice and vegetables cooked together), proving that the structural logic of Indian meals—balancing grains, legumes, and spices—has survived relatively intact for millennia.

Foreign invasions and colonial trade transformed the Indian pantry with staples once considered "exotic."

Foreign invasions and colonial trade transformed the Indian pantry with staples once considered "exotic."

It is a culinary irony that many "iconic" Indian ingredients are actually immigrants. The Columbian discovery of the New World introduced potatoes, tomatoes, chillies, peanuts, and guava to the subcontinent. Before the Portuguese brought the chilli from Mexico in the 16th century, the primary source of "heat" in Indian food was black pepper. Today, these New World crops are so integrated that they are even permitted on Hindu fasting days when other grains are restricted.

Successive waves of cultural interaction added layers of complexity. The Middle Ages saw the rise of Mughlai cuisine—a fusion of Indian and Central Asian styles that introduced saffron and rich meat preparations. Later, British and Portuguese rulers introduced baking and vegetables like cauliflower (1822). This exchange was a two-way street: the European hunger for Indian spices was the primary catalyst for the Age of Discovery, effectively reshaping the map of the world.

The Indian plate is a site of spiritual discipline governed by Ayurveda, Yoga, and religious taboos.

The Indian plate is a site of spiritual discipline governed by Ayurveda, Yoga, and religious taboos.

In India, food is rarely just fuel; it is a component of holistic wellness. Ayurveda, the ancient Indian system of medicine, treats food as a pillar of health alongside meditation and yoga. This led to a sophisticated classification system known as the three Gunas: Saatvic (pure/light), Raajsic (active/passionate), and Taamsic (heavy/dull). These categories still influence dietary choices today, particularly among those following yogic traditions.

Religion remains the most powerful arbiter of the Indian diet. The Śramaṇa movement encouraged the spread of vegetarianism, while the sacred status of the cow in Hinduism created a widespread taboo against beef consumption (with notable exceptions in Kerala and the Northeast). These constraints have fostered incredible creativity in vegetarian cooking, utilizing various lentils (dal), dairy (ghee and curd), and complex spice blends to achieve savory depth without meat.

Culinary "logic" in India is defined by regional fats and the chemistry of the *Bhuna* technique.

Culinary "logic" in India is defined by regional fats and the chemistry of the *Bhuna* technique.

India does not have a single cuisine, but a map of flavor profiles determined by local geography and the available cooking medium. In the North and West, peanut oil is the standard; in the East, pungent mustard oil defines the taste; along the tropical West coast and Kerala, coconut oil is king; and in the South, sesame (gingelly) oil provides a nutty aroma. These fats aren't interchangeable; they are the foundation upon which regional spices are built.

The "secret" to Indian flavor chemistry is the process of bhuna—frying freshly ground spices in hot oil or ghee to create a paste. This releases essential oils and creates a depth of flavor that cannot be achieved by boiling or dry-seasoning. While "Garam Masala" is globally famous, it is not a fixed recipe; it is a regional (or even personal) ratio of spices like cardamom, cinnamon, and cloves, tailored to the specific ingredients of a dish.

Traditional Indian consumption patterns are currently the global gold standard for environmental sustainability.

Traditional Indian consumption patterns are currently the global gold standard for environmental sustainability.

Despite the modernization of food systems, India’s traditional diet remains remarkably efficient. The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) 2024 Living Planet Report highlighted India’s food consumption as the most sustainable among the G20 countries. This is largely due to the historic emphasis on plant-based proteins (lentils and pulses) and a wide variety of climate-resilient grains like millets.

In states like Arunachal Pradesh and Assam, indigenous styles continue to prioritize "simple" cooking—barbecuing, steaming, or boiling—with minimal use of processed fats. The Assamese meal structure, beginning with a khar (alkaline dish) and ending with a tenga (sour dish), reflects a sophisticated understanding of digestion and local biodiversity that precedes modern nutritional science.

Pomegranate

Bhang eaters in India c. 1790. Bhang is an edible preparation of cannabis native to the Indian subcontinent. It was used by Hindus in food and drink as early as 1000 BCE.

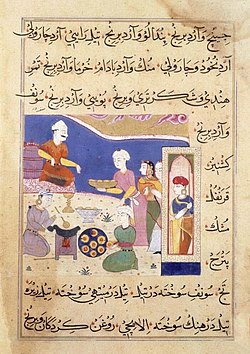

A page from the Nimatnama-i-Nasiruddin-Shahi, book of delicacies and recipes. It documents the fine art of making kheer.

Medieval Indian Manuscript Nimatnama-i-Nasiruddin-Shahi (circa 16th century) showing samosas being served.

Prawn with a Rohu fish, Kalighat Painting. Freshwater fishes and crustaceans are staple diet in eastern regions, prominently in Bengal.

Spices at a grocery store in India

Lentils are a staple ingredient in Indian cuisine.

Indian food at restaurant in Paris.

A vegetarian Andhra meal served on important occasions

Pitang Oying

A lunch platter of Assamese cuisine

Pithe Puli

Shorshe Pabda (Pabo catfish in mustard paste)

Litti Chokha

Punjabi aloo paratha served with butter