Idealism

Reality is fundamentally mental, asserting that ideas—not physical matter—are the primary building blocks of existence.

Reality is fundamentally mental, asserting that ideas—not physical matter—are the primary building blocks of existence.

Idealism is the metaphysical "mind-first" view. It argues that consciousness, spirit, or reason is the ground of all reality. While we often assume the physical world exists independently of us, the idealist suggests that what we call "matter" is either a product of the mind or entirely composed of mental energy. This stance places idealism in direct opposition to materialism (the belief that only matter is real) and dualism (the belief that mind and matter are separate).

Because the term covers such a vast range of thought, it is rarely defined uniformly. However, the core thread is the "primacy of consciousness." Whether it is George Berkeley arguing that "to be is to be perceived" or modern panpsychists suggesting that even fundamental particles have a trace of mentality, the idealist insists that the universe cannot be understood without starting from the subjective experience.

The tradition splits between claiming reality *is* mind versus claiming the mind is our only lens for reality.

The tradition splits between claiming reality *is* mind versus claiming the mind is our only lens for reality.

Philosophers generally divide idealism into two camps: Ontological and Epistemological. Ontological (or Metaphysical) idealism is the "hard" version; it claims that reality itself is non-physical or immaterial at its core. If all minds were to vanish, the universe—as we understand it—would cease to exist because its "being" is grounded in thought or spirit.

Epistemological idealism is more of a "soft" or "formal" constraint. Popularized by Immanuel Kant’s "transcendental idealism," it doesn't necessarily deny that a physical world exists "out there." Instead, it argues that we can never know that world directly. We are forever trapped behind the "veil" of our own mental structures (like time, space, and causality). In this view, we don't study things as they are, but only as they appear to our human mental hardware.

From Plato’s "Forms" to India’s "Mind-Only" schools, idealism emerged as a global answer to the limits of the senses.

From Plato’s "Forms" to India’s "Mind-Only" schools, idealism emerged as a global answer to the limits of the senses.

Idealism isn't a modern Western invention; it has deep roots in ancient global thought. In India, the Vedanta and Yogācāra schools argued for an all-pervading consciousness (Brahman) or a "mind-only" (cittamatra) reality long before European Enlightenment thinkers. These systems used the analysis of subjective experience to argue that the external world is an emanation or a construction of a deeper, singular consciousness.

In the West, the lineage begins with Plato, who proposed that our physical world is just a flickering shadow of "Forms"—perfect, unchanging, and timeless ideas that exist in a higher realm. Later, Neoplatonists like Plotinus pushed this further, suggesting that the entire universe is a hierarchical procession originating from "The One." This historical trajectory shows that idealism often arises when thinkers realize that sensory data is too unstable to serve as a foundation for "Truth."

Modern idealists scale the "mind" from the microscopic behavior of quarks to the vast consciousness of the entire cosmos.

Modern idealists scale the "mind" from the microscopic behavior of quarks to the vast consciousness of the entire cosmos.

Today’s idealists use a varied taxonomy to describe how mind and matter interact. "Micro-idealism" suggests that the smallest building blocks of reality—like quarks or photons—have a fundamental mental component. "Macro-idealism" focuses on the level of human or animal consciousness. Meanwhile, "Cosmic idealism" posits that the entire universe is a single, conscious entity, often aligning with pantheistic or theistic views where the world is essentially "God’s thought."

This spectrum allows idealism to survive even in an age of hard science. For example, David Chalmers notes that one can be a "realist idealist," accepting the laws of physics but arguing that those laws actually describe the behavior of conscious subjects rather than inert "stuff." This avoids the "hard problem of consciousness"—the mystery of how "dumb" matter produces "smart" thoughts—by assuming the "smarts" were there from the beginning.

Idealism provides a philosophical bridge for theology, framing the physical world as a "divine dream" or spiritual distortion.

Idealism provides a philosophical bridge for theology, framing the physical world as a "divine dream" or spiritual distortion.

Theistic traditions have long used idealist frameworks to explain the relationship between a Creator and the creation. In Kabbalistic idealism, the world is likened to a fictional tale told by God. In Christian Science, the material world is seen as a "distortion" of an underlying spiritual reality; healing and "truth" are found by reorienting the mind away from the senses and back toward the divine idea.

By asserting that mind is the "world ground," these religious perspectives solve the problem of how a spiritual God interacts with a heavy, material world. If the world is already made of "thought-stuff," then the gap between the human and the divine is not a distance of space, but a clarity of perception. This renders the universe not a cold machine, but a meaningful, mental, and participatory experience.

Detail of Plato in The School of Athens, by Raphael

The Upanishadic sage Yājñavalkya (c. possibly 8th century BCE) is one of the earliest exponents of idealism, and is a major figure in the Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad.

Śaṅkara, by Raja Ravi Varma

Statue of Vasubandhu (jp. Seshin), Kōfuku-ji, Nara, Japan

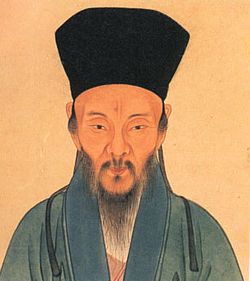

Wang Yangming, a leading Neo-Confucian scholar during the Ming and a founder of the "school of mind"

A painting of Bishop George Berkeley by John Smibert

Hegel's The Phenomenology of Spirit was a pivotal work of German absolute idealism.

F.H. Bradley, a leading British absolute idealist

Charles Sanders Peirce

The 20th-century British scientist Sir James Jeans wrote that "the Universe begins to look more like a great thought than like a great machine."